Episode notes:

Episode Transcript:

Paul Gilmartin: Welcome to episode 34 with my guest Paul F Tompkins Paul Gilmartin this is the mental illness happy hour an hour of honesty about all the battles in our heads. From medically diagnosed conditions, every day compulsive negative thinking, feelings of dissatisfaction, disconnection, inadequacy, and that vague sinking feeling that the world is passing us by. You give us an hour we will give you one hot ladle of awkward and icky. This show is not meant to be a substitute for actual professional medical advice, I’m a jackass that tells dick jokes. This is not a doctor’s office, think of it as a waiting room that hopefully doesn’t suck. But first before we get to Paul’s interview a few notes.

As I mentioned on the, the last the podcast T-shirts are now available, Mental Illness Happy Hour T-shirts they’re, uh, they’re 25 bucks and you can get them at the website mentalpod.com you can also support the show there by making a donation through PayPal, uh, buying something through our Amazon search link. Uh, you can go to the forum there—I’ve been really touched by the, the number people that have started posting stuff on the forum and helping each other out, connecting and expressing love and support for each other. It’s really, really touching and I want to thank the, the guys that help keep the spammers out of that. Eternally_Learning is one guy and BCZF is the other guy. That’s their, uh, their handle. Is that what you call it? When you’re on the forum? Anyway, um, thank you t-to all you guys.

Um, it was an interesting week. A friend of mine called me from the emergency room and she was having a nervous breakdown and, actually, the paramedics had to bring her there because she was shaking so badly. And, uh, she couldn’t drive. And, you know, when I asked her what was going on, in a nutshell, she feels like her life is collapsing around her. She used to have a powerful position in her industry and now she’s unemployed. Um, she broke up with somebody, uh, that she had lived with for a while, and, I, you know what, I know that feeling, when you feel like the rug is pulled out from underneath you. And it feels like there’s nothing you can do to protect yourself from stuff like that happening. And while we can’t protect from things happening to us, I think what we can do is create a part of our lives that can’t explode, that can’t be—have the legs cut out from underneath it. And what I’ve discovered is engaging in stuff that doesn’t have to do with my ego is the only stuff that can’t be destroyed. Um, doing volunteer work, doing something nice for somebody else, uh, uh, especially if nobody else knows about it. If it’s completely anonymous. Um, because, when, when I do those things, there’s no—it can’t be popped. You know? Nobody can come in and cut the legs out from underneath that. Uh, I think of this story that Eric Clapton tells when he was at the height of his—people worshiping him as a guitar god, he read a review of, uh, of one his albums, in Rolling Stone and they completely dismissed it and said that his playing was derivative and he was ripping off old blues guys. And he says he fainted. And that to me proves that it was ego-based. Because ego-based things can always have the legs cut out from underneath them because they’re dependent on other people’s opinions of us. And, if you cultivate an area of your life that is kind of good, and pure, and selfless, when all the other stuff collapses, the landing, to me, is softened, because you always have that to fall on. And then you don’t believe that lie that ‘I am nothing. And my life is disappearing.’

[SHOW INTRO]

Paul Gilmartin: I’m here with, uh, Paul F. Tompkins. Uh, can I call you Tomcat? Does anybody call you Tomcat?

Paul F. Tompkins: (laughs) No, I don’t know what’s taken so long.

Gilmartin: Has anybody ever called you Tomcat?

Tompkins: No, no, no, no. Apparently they used to call Tom Kenney that. Back in the—

Gilmartin: Really?

Tompkins: Yeah, it was him and, um, uh, Bobcat Golthwait. Bob was Bobcat, Tom was Tomcat.

Gilmartin: Makes perfect sense.

Tompkins: And I think Paul Kozlowski was Paulcat or Polecat.

Gilmartin: Polecat

Tompkins: Depending on your pronunciation. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

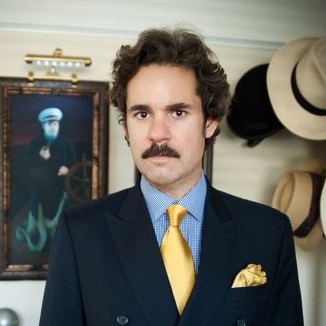

Gilmartin: Uh, for those of you that don’t know, uh, Paul F. Tompkins and there’s probably—

Tompkins: Oh, there’s more to it?

Gilmartin: Oh, there is!

Tompkins: Oh, I thought that was it! I thought you just had me by for, uh, for that.

Gilmartin: (laughs) Just, uh, just to call you Tomcat?

Tompkins: I guess I haven’t listened to the whole podcast.

Gilmartin: You should. You should, you should listen to the podcast.

Tompkins: Well I was busy.

Gilmartin: Yeah. You thought this was just an assigning a nickname podcast.

Tompkins: I thought it was like a four to seven minute podcast. And I’d always get halfway through it and, oh, I gotta, I gotta run.

Gilmartin: Oh my God this is very awkward. I’ve gotta be much—I’ve gotta reveal more information in my emails when I solicit people t-to come on the podcast.

Tompkins: I never got as far as the introductions. I would always think, “I wonder who that was?”

Gilmartin: You’re really impatient.

Tompkins: Well, it’s a flaw.

Gilmartin: We’ll get to that. We’ll get to the roots of that. Because that’s what this—but you wouldn’t know that.

Tompkins: Oh, that’s true.

Gilmartin: I just caught you.

Tompkins: You did.

Gilmartin: You so don’t flesh out your characters. You are really … a rank amateur. I, uh, for those of you who don’t know Paul F. Tompkins, he, uh, i-is in my opinion one of the standups working today. Uh, I’m alone in that opinion, because most people find him, um, intolerable.

Tompkins: Insufferable.

Gilmartin: Uh, long-winded.

Tompkins: Unbearable.

Gilmartin: Unbearable. Un, any word that begins with “un”.

Tompkins: “Un”, “anti”, “non”.

Gilmartin: Paul, Paul was a, uh, a writer and performer on the ground-breaking HBO sketch show Mr. Show. Uh, he has a podcast that is absolutely one of the funniest, most original podcasts out there. It’s called the Pod F Tompkast. If you haven’t heard it, is—I was, I was talking with somebody the other day about podcasts, and we were both saying how excited we are whenever one of your new episodes c-comes out. And we were like—

Tompkins: Thank you.

Gilmartin: Literally, it’s like comedy Christmas when your, when your episodes come out.

Tompkins: Thank you very much, Paul.

Gilmartin: It, uh, it’s—your sense of humor, um—and here’s one the reasons why I’m a little, uh—why I was a little surprised that you, that you felt you qualified to come on the show, because your sense of humor has a lack of hate in it that is really refreshing. It’s—Paul’s sense of humor is—it’s very literate, and it’s, uh, it’s got, uh, a silliness to it, and it’s got kind of a tangential, uh, abstract—

Tompkins: I’ll say

Gilmartin: Quality to it. A-and it is—there’s nothing like it .There’s nothing else like it. And, uh, but there’s almost like—a-and I don’t, certainly don’t mean this as a putdown, this is something I strive—there’s a childlike vulnerability in it that is unprecedented in comedy. I suppose you could go back to the 50s or 60s and find, um, comedians th-that had that kind of vulnerability, but their comedy wasn’t funny. There wasn’t, there wasn’t any—

Tompkins: I think I know you what you mean. You know who I would say though i-is like that, and it’s somebody that I, um, uh—was a, was a great example to me, i-in—wh-where I—how I arrived at th-the style that I have today. Um, is Brian Regan. Because Brian Regan was a guy—one day it dawned on me—his comedy is always directed inward. It’s always about him being the dumb person, it’s always about him being the screw up, you know. It’s not about, um, uh, easy targets and taking down, um, uh, people that are less than him. It’s always—what makes it so relatable is—here’s where I fucked up, and here’s where I feel dumb. You know, and, like, the idea of—that’s not a thing you see, really. Somebody—an observational standup comedian who just gets up there and talks about everyday stuff wh-who’s coming from the point of view of ‘This thing makes me feel uncool and stupid.’ You know, whereas so much of what we do is about, you know, being in control of the audience. You know, and projecting a confidence. It’s like, ‘Listen you guys, everything’s gonna be OK because I’m so cool. I’m gonna make fun of some shit that you’re gonna enjoy me making fun of and everything’s gonna be fine.’ And when I—it kind of dawned on me like, oh, this guy is doing something that is, is so—it’s so welcoming in a way that you don’t even realize that it is. You know, that the audience isn’t thinking about that, you know. But it’s a—it strikes a nerve that people don’t realize they want struck. You know, like, ‘I thought I was the only person who was dumb.’

Gilmartin: Right. And it’s, it’s refreshing in it’s lack of cynicism, uh, that’s the thing that I enjoy about your comedy, is, it’s so uncynical and I love that, at the beginning of the podcast, you know, the introduction to it, they say, you know, “Performed for a, uh, uncynical audience.” And, and, you know, I would say this to Jimmy—you and Jimmy Pardo to me are anomalies in that you guys can perform for a room full of hipsters, you can work G-rated clean, and get these people, and Jimmy can, can kill in front of crowd, and crowd on the road, and kill in front of a room full of hipsters. And that to me is: a, the sign of originality; and, b, just fucking amazing, uh, to me, uh. But I imagine you didn’t get to that, to that place, uh, right out of the gate.

Tompkins: No.

Gilmartin: Well, I, I don’t, I don’t want to—and—I don’t want the focus of this, um, of this episode to be too much about comedy, because there are other podcasts that, you know, I think Marc Maron does what he does. And while there are areas of our podcasts that overlap, I-I try to consciously avoid not treading territory that, uh … So, I would like to start with, um—I don’t know, where do you think would be a good place to start since you kind of know what you feel makes you relatable to the theme of this show? Where do you think would be?

Tompkins: Well, I, I think that like a lot of your guests, uh, wh-who are performers of some kind, you know, um, a-and I’ve listened to just about all the episodes, I think.

Gilmartin: Oh you have?

Tompkins: Of your show, yeah.

Gilmartin: Really?!

Tompkins: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Absolutely.

Gilmartin: Wow. That-that—I’m incredibly flattered.

Tompkins: No. And, well, it’s a lot of people that I know, you know, so that, you know, I have, uh, people that are, uh, sort of my gateway guests on podcasts. That’s how I find things. S-s-so sometimes I’ll do a search for my friend Jen Kirkman, you know, and I saw that she was on your show, so that—and I didn’t even know that you were doing this podcast, you know. And that’s how I found out about it.

Gilmartin: I didn’t even know I was doing this podcast.

Tompkins: Wait, how many episodes in did you find out?

Gilmartin: About the sixth one. I found myself editing and I went, ‘what?’

Tompkins: And it feels like a betrayal.

Gilmartin: (laughs)

Tompkins: So, I started listening, and, uh, I was, uh, I was in—I got into it immediately, um, and, uh, I think wh-what I share with a lot of people, and what a lot of performers share is, there was something early on, you were not getting enough of, whether it’s love or attention, or, um, or both, or, uh, whatever magical combination it is that some people—we think some people are getting—that makes them not do what we do, you know. Um, and for me, it definitely was, um, you know—

Gilmartin: You mean, you when I was talking about my childhood, not getting enough love or attention, or you mean professionally I wasn’t getting enough?

Tompkins: Take your pick. No, but, you know, I mean, I think it starts with, it definitely starts with childhood, and i-i-it’s, you know, a very common story, uh to all of us. Um, and, uh, you know, I-I was the fifth out of six children, you know, growing up with, uh, a-a-a mother who was, uh, just flat out burnt out, you know. Just by the time I came along, um—this was somebody, you know, from the, uh, Depression baby, you know, who, uh, I think, you know, my relationship with my mother, who passed away in 2007, I think, has informed, uh, just about all the choices that I’ve made in my life up to a certain point, you know. Um, because this was the person that, uh, this was the audience member for how many decades of my life, you know, the person that I was trying to make, um, trying to get the approval, trying to get the, uh …

Gilmartin: Was she a good audience for you?

Tompkins: No.

Gilmartin: No?

Tompkins: She sure wasn’t, no. TH-that’s why.

Gilmartin: I also heard you—I listened to you on, on Marc Maron’s podcast, and you said that your dad also wasn’t a really—

Tompkins: Dad—super remote. To this day, my relationship with my dad is—he—I-I’ve described it a-as, uh, you know, being with him is like being with the friend of a friend that I don’t know that well and, um, I’m struggling for, uh, any kind of conversational ‘in’, like, what—how can I get more than a one word answer out of this guy? Just the fact that I refer to my dad as ‘this guy’, like, a lot, a lot. Um, you know, but my mom was the person that—she—because my dad went to work all day, and then he would come home and he would go off into his world, you know. He would go up into his room where he would watch his television, read his newspaper, you know, that kind of thing. Um, and he was done for the day, you know. Uh, so like the socializing with the family was not a thing that he did. Um, their marriage was, uh, pretty much over from my earliest memories. You know, I never saw them exchange any affection, uh, at all, you know. Um, that was—

Gilmartin: B-but they stayed married.

Tompkins: But they stayed married. Because that’s what you did, you know?

Gilmartin: That’s exactly—I-I’ve never seen my parents, uh, express—well, my dad’s gone now—but I-I never saw them express love to each other. And, uh, it’s weird when that’s, when that’s your, your role model because it’s, like, it’s so bizarre. There’s almost like a deadness, uh, in your, in your house that’s walked around and not talked about. How do you, how do you think that, um …

Tompkins: That’s a really good way to put it. Because it like this thing of, like, are we not gonna talk about this at all? Like that fact that this is a weird arrangement? Like you two clearly are not on board with each other any more. What are we all doing here, you know? And that is how it felt to me. And I remember, I remember as, as—how old was I? Like, twelve, thirteen, and I—my mother had a lot of anger. And—which, uh, she was kind enough to pass on to me. Um, I inherited that from her. Um, she—I would hear her, um, kind of rail against her life, like, in the kitchen, banging things around, you know?

Gilmartin: Really?

Tompkins: And her, her—she was a person who felt clearly overwhelmed by her circumstance in life. She had to take care of all these kids, she had a job, she had this husband that she felt was not helping out in any way. A-a-and I guess my dad’s view, um, view on things was: he had a job, he worked all day, and that was—he was done. He was fulfilling his part of the bargain. He was providing for the family. So, like, the idea of washing dishes, on top of that, that’s not gonna happen. You, especially—

Gilmartin: Especially for that generation.

Tompkins: Yeah, exactly. And I think they were so—and I think my mother’s frustration was, she did everything that was asked of her by her time and her, um, social status, her, uh, her religion, you know, all the things that—she did everything that she was expected to do and nobody said “thank you”. And nobody said “good job”, and nobody said, um, uh, “Hey, eventually you’re gonna get this.” You know, like, th-the closest she got to that was, uh, the church saying, “Your reward is in heaven,” you know. But mostly what she got was—

Gilmartin: You where raised Catholic?

Tompkins: Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Went to Catholic school, you know, uh, for, for twelve years. And, uh, you know, w-was devout for that time.

Gilmartin: You were?

Tompkins: Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: Really?

Tompkins: It was not until I got out into the world—I-I started doing standup at seventeen—um, and moved downtown, and, uh—

Gilmartin: Philadelphia?

Tompkins: Yeah. And started meeting other people and experiencing other points of view and then that gradually, you know, very steadily fell away. You know, all my faith fell away. Um, and, uh, I-I-I was very much i-in the mold of my mother, you know, a, um, a person who was doing what they were told to do, uh, to a certain extent. Obviously, you know, embarking on a career in show business was definitely going my own way. That was not, uh, a thing in my family. M-my oldest sister, uh, actually tried it, um, and then that eventually stopped, you know. Um, she did not go as far with it as I did. But I was, uh, I was in it to win it, you know. And—

Gilmartin: What a waste of—it, it, it’s just—it’s almost tragic to me to think of somebody as funny as you not getting any response from either parent. You know, I at least had my mom, but you had neither parent enjoying—did either of your—did any of your siblings find you funny?

Tompkins: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And, and—

Gilmartin: Did you all make each other laugh?

Tompkins: Oh, yeah, w—we’re a funny family for sure. And my parents included, you know. Even my dad in his way every once in a while will get off a good one, you know. But, uh, but my mother was very outspoken and, uh, she liked to laugh, you know. And that’s what made it so maddening, that I could never really get the approval from her, which f-f-f-for me, for what was for me my number one thing, was that I was funny. Because I would make all my friends laugh at school. And it was, it was—a-and some of the teachers too. It was like, it was an acknowledged fact that I was funny, that I couldn’t really purely get my mother to laugh. And the response anything, uh, that I would try to do to get her to laugh was either, uh, an explanation of, like, you know why that is? Or, or a—

Gilmartin: Which is just soul-deadening.

Tompkins: Oh, it’s so frustrating! So frustrating. Or, she, or it was not the time, you know. Or she was, like, she was not in the mood for jokes.

Gilmartin: Do you think either of your parents were, uh, like, maybe clinically depressed?

Tompkins: Oh I think mother probably was, yeah. My dad, who knows?

Gilmartin: Yeah. Were either of them drinkers?

Tompkins: No, not to any great extent. M-m-my dad probably drinks more now as, as an old retiree than he ever did. You know, he would have, like, a beer after work, you know. But, um, but not really, uh, not, it was not a big deal, you know

Gilmartin: So, w-what do you—like, when you would try to make your mom laugh, and, and it would get nothing, do you remember kind of what, what that felt like?

Tompkins: Oh, it was embarrassment and shame, and, um, the most extreme disappointment. You know, like, because it’s, it’s that thing of: I was putting myself out there again and again and again. And, like, just the frustration of it, like, man, this—a-a-and a thought you can’t form as a child, but, “Wow! This lady does not care for me, you know. Like, I am a burden this person.” Because my mother’s whole thing was, “Nobody will help me. I am doing all of this by myself.” And, you know, like the way she would refer to us was “you people”. And, “None of you people are helping me out,” you know.

Gilmartin: She would say that?

Tompkins: Yeah, yeah, yeah. It, it was, you know, she couldn’t understand, like, to her it was, there’s all these people in the house, but she has to do everything. And, um, a-and—from, from, you know, a very young age, the idea that, uh, you know, I-I was a bad child. Because I was not helping her out. But it’s—I didn’t have the—

Gilmartin: And you weren’t any worse than the other siblings in her mind?

Tompkins: That was never pointed out. You know, that was never pointed out. I don’t know that I was ever made to feel, you know, that—I don’t know that I was ever singled out, you know, in that way.

Gilmartin: Would she let you know in no uncertain terms that you were th-tha-thankless and ungrateful?

Tompkins: Yes. “You’re not sorry, you’re thoughtless,” was a phrase that was used, uh, very often. When it was pointed out that I was not doing something that I should be doing, or I was not doing something as well as I could be doing, or that it didn’t occur to me to go do something on my own that would help out around the house. And I would say, “I’m sorry.” And she would say, “You’re not sorry. You’re thoughtless.” Which—

Gilmartin: That’s so harsh.

Tompkins: Oh, it was horrible. It was horrible. Because I really—I lacked the understanding of what was going on.

Gilmartin: Exactly, the dynamic that she wasn’t getting anything. And when you’re getting nothing, you have nothing to give.

Tompkins: But I didn’t know, like, as a child, like—of course, as an adult, y-y-you know, a-a-around the house, uh, when I would go back home and visit, and I would see things that needed to be done, I would do them. Because I’m a grown-up, you know. But as a child, like, ten years old, like, I don’t know, like, oh, I should go pick that stuff up, you know, and go put it away. I should sweep the front steps. You know, like, I don’t know stuff like that. I-I-I’m like, you know, I’m a kid, you know. And, so …

Gilmartin: Yeah, you don’t know that your mom is being treated like a second class citizen by society.

Tompkins: Exactly!

Gilmartin: And that she’s getting no physical affection from her husband, you know—

Tompkins: And that the world is changing, you know. Uh, I was born in ’68, you know. So, growing up in the ‘70s—

Gilmartin: You were born in the middle of a riot, correct?

Tompkins: Yeah, pretty much, yeah (laughs). That’s right. Conceived and born, conceived during one, born during another. Um, that, that, you know, I-I’ve recently watch um, that, uh, that, um, Gloria Steinem documentary.

Gilmartin: Great documentary.

Tompkins: Fantastic. And, really, it’s important that people see that, because, I-I—now. Because we, we’re kind of lulled into thinking, like, oh, you know, everything’s equal now. It’s still not.

Gilmartin: No.

Tompkins: Like the fact that the Equal Rights Amendment was never passed, still not, still can’t get passed, is insane. Like, th-th-that they just, not too long ago, reaffirmed—o-o-our government took time out to reaffirm that ‘In God we trust’ is still the national motto. Nobody was ever contending that, but, like, we can’t get to people to agree, like, yeah, women are equal to men, right? Like, a-a-and should be paid the same. Like that’s not on “the books”, is crazy. The Catholic Church has gotten rid of limbo, the place where unbaptized babies go when they die, like, the Catholic Church admitting, like, “Oh. Alright, that’s not a thing. That’s not a—of course babies go to heaven if they die.” Still, we cannot get in this country everyone to sign off on the idea that women should be paid the same as men. Like, to have it written down. So, my mother was, was, um, you know, raising kids at this time when the world was trying to change, and America was trying to change, and there was all this upheaval. And I think she was looking around saying, “What the fuck? Why am I still—where’s my—where’s that happening for me?” You know? And …

Gilmartin: Was she supportive of, uh, the Women’s Liberation Movement, or was it just not discussed and it was just something kind of in the peripheral background?

Tompkins: It was not discussed. But my mother would say things like, like, if there was an old movie on TV, um, or even like an episode of Columbo, or something like that, and uh, you know, if it was some thing where, um, you know, th-th-the criminal, uh, like a-a-a-a double indemnity kind of situation, the criminal does it all at the woman’s, uh, urging. You know, a kind of Lady Macbeth scenario. I remember my mother—I remember this so—because she said it more than once, very dryly, saying, to no one in particular, “It’s always the woman’s fault.”

Gilmartin: (laughs) Wow.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. That, that stuck with me, man forever, you know. And then, of course, you see it in stuff, you know.

Gilmartin: A-a-and how could she even begin to have that conversation with your dad cuz he’s completely shut down.

Tompkins: He apparently made his feelings known on the matter, which was, uh, you know, that’s the way I am. You know, he was a messy guy who was not gonna lift a finger to clean up his own mess, much less help out with anyone else’s mess. He wasn’t gonna put toys away, he wasn’t gonna, you know, uh, do any of that kind of stuff. So, um, and once we were old enough, um, to rake leaves, the idea was like, ‘Oh. Well, they’re gonna do it.’ You know?

Gilmartin: I-i-it—there’s this dynamic that’s so common w-w-with our parents’ generation where they, they had no idea what a relationship was gonna be like, what having kids was gonna be like. They had the kids and then they opened the present and realized, ‘Oh my God. This is not what I thought.” But then you’re in. A-a-and you go to a church on Sunday that tells you, “Oh no, you’re in.”

Tompkins: Yeah. They had been, they—from a time that, uh, it was, ‘Well, that’s just what you do.’ You know, if your marriage is in trouble, well then fix it. Or you suffer through it, you know. You stay together for the kids, like, everything, uh, from their generation was telling them, uh, ‘Shut your mouth. And just do what is expected of you.’ You know. And I think my mother had issues with that. And I remember her saying, years before she, um, converted to atheism, um, just before she died—

Gilmartin: Which is a beautiful ceremony.

Tompkins: It’s (laughs) it really is. I mean you really should go all out, you know. Get it catered. Um, she, she would say, “I’m a Catholic in spite of the Church.” So she had her issues with it. But she still had her faith. And I think that she was holding on for as long as she could, like, waiting for a payoff with all of this stuff. And it never came. And now when I think about it, I think of, of the crushing disappointment she must have felt, like, ‘Man, oh, man. I did all this stuff that I was told to do, and what did it get me?’ You know. And I-I-I mean, she—I think she liked us more as adults than she did as kids, you know.

Gilmartin: Do you think that’s because her responsibility to you was now much easier?

Tompkins: Oh, absolutely.

Gilmartin: She didn’t have to pick up after you.

Tompkins: Absolutely. Now she could just love us.

Gilmartin: Now she could enjoy you as people and didn’t have to worry about what kind of a human being I’m sending out into the world.

Tompkins: Absolutely, yeah. Yeah, yeah. And we all turned out pretty much ok. We all have our problems for sure, you know. And I-I will not, you know, I—it’s not, it’s not for me to discuss, I think, all of my siblings’ issues. Everybody’s got ‘em, you know. And we all—we are no different than any other family. We all have our issues.

Gilmartin: I don’t see how anybody could come out of a loveless situation like that and not be fucked up in some way. I-i-it imprints something on you that you’re-you’re-you’re not comfortable with people—like, I remember, uh, getting out into the adult world and sometimes, like, dating women that were very affectionate, and were very bubbly, and were very happy, and I remember something inside me wanting to snuff that out because it made me uncomfortable. Because it was so foreign. You’re happy for no reason. I remember saying, uh, uh, to a date of mine one time at a party in high school—she just smiled this beautiful smile at me, and I said, “What the fuck are you smiling about?” Good God.

Tompkins: You actually said that? (laughs)

Gilmartin: Good God, I felt rage. I felt rage because I thought she looked lame. Oh, God.

Tompkins: (laughs) Feels like a fool, a damned fool.

Gilmartin: I actually, I actually thought that. That is how foreign that—

Tompkins: Don’t you realize how awful everything is?

Gilmartin: Yes!

Tompkins: You idiot!

Gilmartin: What—how do you not know that the world is a sizzling cauldron of contempt and disappointment? You idiot! You know, that’s, that’s what I remember feeling.

Tompkins: But also, because she was directing that at you.

Gilmartin: Yes

Tompkins: She was happy to see you.

Gilmartin: Yes. And I thought, ‘Don’t you know I’m a piece of shit.’ You know, I couldn’t, I couldn’t construe that in my brain, but that was the—and it, and it expresses itself as just this kind of vague rage.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I had loathed myself for such a long time that by the time my girlfriend, then girlfriend, now wife—

Gilmartin: W-w-what were your thoughts towards yourself when you said you loathed yourself?

Tompkins: Oh, I—there was just nothing good about me. You know, like, th-the—I-I-I was ugly, I was, uh, uh, you know, uh, lazy, I was thoughtless, I was, you know, all of these things. I was not a good person. You know, that’s what I, that’s what I thought.

Gilmartin: Talentless, immoral, thoughtless.

Tompkins: Yeah.

Gilmartin: Unattractive.

Tompkins: Absolutely. Everything. Everything.

Gilmartin: The greatest hits.

Tompkins: (laughs)

Gilmartin: The Catholic greatest hits.

Tompkins: And many more.

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: Yeah. Every—there was just, uh, I-I-I was just not measuring up in every way possible. And, uh, like, the religion on top of it for so long. That I was disappointing Almighty God.

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: Because I grew up in a time when, um, where Catholic guilt shifted from, um, you know, it used to be, you know, if you do these things, uh—like, in my mother’s time, it was if you do such-and-such, you will make God angry. But, me, post-Vatican II, it was if you do these things you make God sad. You know, you’re really letting God down. Who—God just loves you so much and if you sin, you’re hurting God’s feelings. You know, so it shifted from just the fear of Hell—it’s almost like God doesn’t want to send you to Hell, but you’re leaving him no choice.

Gilmartin: God is gonna have to send you to Hell and it’s gonna make Him cry.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah, you know.

Gilmartin: So you were, uh—I-I-I—y-y-you were starting to say, y-y-you had a date—

Tompkins: So, m-my girlfriend, one, one day we were at the—

Gilmartin: You were how old at this point?

Tompkins: Th-this is just a handful of years ago.

Gilmartin: OK

Tompkins: We were at the gym, we ended up at the gym at the same time. And I was getting off a machine and I hear her call my name, and I turn around and she had this huge smile on her face, and it was the first time in my life that I consciously felt good about somebody being happy to see me like that. Where, it, like, i-i-it was like nothing—you know, people have smiled at me before. But there was something about this, that it was like, it made me feel like a good person.

Gilmartin: Wow.

Tompkins: Like I was—it made me feel like, for the first time, like, oh, maybe I’m worth that sort of—somebody looking at me that way. Like, somebody—maybe it’s OK for—to feel like somebody should be that happy to see me, you know.

Gilmartin: Yeah. And I’m not a fraud for taking it in.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. For the first time, it made me feel like, ‘Hey. Maybe I’m not an awful person. Maybe I am worthwhile.’ You know. But I had never, never really—and at that point I had been in, in therapy for a number of years, but still couldn’t quite bring myself to like myself.

Gilmartin: What do you think got you to that, to that—maybe this is jumping forward, but, uh, how did you, how did you get to that—I mean—

Tompkins: It was, it was work, you know. Pure and simple. It was—uh, it was going to therapy, um, every week, uh, and really, but really, taking it seriously, like, this is—I-I’m going to be as, as honest as I possibly can in here. I’m gonna try to catch myself any time I-I’m like, trying to wriggle away from something. Because, you know how easy it is to do. It’s like, we get so used to, uh, uh, uh, reframing a narrative a-a-and telling the story Rashomon style, “Well, here’s what happened.” Well, it’s like, maybe not really what happened. That’s how, that’s how—that’s your interpretation of the thing.

Gilmartin: And talking about it with saying how it made you feel. Because ultimately, to me, what therapy, really good, productive therapy is saying, “It made me feel … such-and-such.”

Tompkins: Yeah.

Gilmartin: “I felt such-and-such.”

Tompkins: Yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: What, do you remember, got you to the breaking point where you said, “I need to go get help.”

Tompkins: Oh, absolutely. I-I—my pattern was with relationships, I would fall in love with someone who was never really going to love me back. And it was the, uh, repeating the pattern with my mom. Trying to get that approval. And it’s like, well, clearly I have to get—I have to go after the most impossible person. Because if I can win their love, then—obviously, this is all—I’m not consciously thinking this, but inside, it’s like, ‘I will break that—I-I-I will finally have solved it.’ You know. And then I won’t need my mother’s love anymore.

Gilmartin: And it’ll be a delicious victory.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: I’m winning the World Series. You know, anybody can and, and win the love of somebody has a great mood and is happy to begin with, but where is the victory in that?

Tompkins: Yeah, absolutely.

Gilmartin: But if I can turn somebody around.

Tompkins: Yeah. So I was friends with this woman, we were close friends, and, this was somebody that absolutely of all the people in my world, this would be the person to not try to have a relationship with. And, knowing that—not only—it was a total non-starter. It was never even going to a failed relationship. She was not going to be on board with it, as soon as I brought it up, which is exactly what happened.

Gilmartin: Female friend, like you said, I like you—

Tompkins: Female friend. “I have feelings for you.” It was met with, um, uh, anger. She was—

Gilmartin: Anger?

Tompkins: Yeah.

Gilmartin: Why anger?

Tompkins: Because she knew it was the end of the friendship.

Gilmartin: Oh.

Tompkins: Because she had been down this road before with somebody else. She knew it was gonna be awkward, uncomfortable. She knew that I was gonna have a weird anger towards her for not loving me. A-a-all of it, exactly what happened.

Gilmartin: Really.

Tompkins: Exactly what happened.

Gilmartin: Was this a professional peer or just a friend?

Tompkins: Both.

Gilmartin: Ok.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So it was—we had this very, um—this relationship that would ping pong back and forth between, uh, really good and really tense, and, uh, and uncomfortable.

Gilmartin: This was after you expressed this to her.

Tompkins: This was after I expressed it. And it, we—

Gilmartin: Do you remember what she said to you when you said, uh, I’d like to be, you know, I’d like to be more than friends?

Tompkins: She, she—well, I, I called her up, I blurted it out, and then I hung up the phone. And then, I-I can’t remember, was it later that day, or a day later?

Gilmartin: Were you just waiting then for the phone to ring?

Tompkins: I-I—oh, man, I don’t know that the fuck I was waiting for. I don’t know—I think I was waiting for the earth to swallow me up at that point. I—there was that feeling of ‘I should not have done that.’ But I was so compelled to do that.

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: I had to do it.

Gilmartin: Yes!

Tompkins: Uggghhhh. Like the pit of my stomach. Horrible. Horrible. Um, and mortified! Mortified! Why did I do that?

Gilmartin: What a, what a prison to be in. When you’re compelled to do something that shames you. Especially if it becomes, like, you know, something that—a compulsion that you, that you do over and over again.

Tompkins: Yeah!

Gilmartin: Like, you know, overeating, or getting too drunk, or, or, whatever it is. And you know, ‘Oh my God. Here’s that feeling again. I’m gonna do this. I-I can’t stop myself.’

Tompkins: What made it so horrible was, I still—I still had enough of that, uh, you know, that, um— (leaf blower noise in background)

Gilmartin: By the way, I invite the, I invite the leaf blowers. Whenever I know I’m gonna have somebody over for the podcast, I say, “Please. Clear the immediate area of all leaves.”

Tompkins: I think it adds a nice subtext to everything. Where it’s, like, this –cuz this is, this is what it’s like in your mind when you got this stuff goin’ on, it’s as annoying as a leaf blower. Um, I, I, I still had enough of that, um, that romantic, cinematic delusion that you, that you have as a, as a kid, that you have in high school—

Gilmartin: That sliver of hope.

Tompkins: It’s so dumb. I mean, when I think about it. It’s still, it’s still hard for me not to dislike the person that I was, to really have contempt for the person that I was. Um, I cringe when I think about my past self, you know. And it’s all like—I’m not a completely different person but I am a very different person in many, many ways. Um, so when I think about, uh, I-I, oh, when I think about that, like, there was still—

Gilmartin: Can I, can I share an awful one?

Tompkins: Sure. Please.

Gilmartin: Uh, I was about 22 years old, had just graduated from college, I—it—I was making my rounds, going to auditions in Chicago, and I was represented by this agency that also happened to handle models, and so I struck up a conversation with this gorgeous model. Way out of my league. Too nice to say, “Stop bothering me.” I show up at her apartment one night (laughs), this is so fucking embarrassing, and she is showing—she’s amused by me. You know what I mean? She finds me funny, but there’s no—not a hint of I’d like to take this to the next level with you. Out of nowhere I (laughs) ask her if she wants to take a bath.

Tompkins: Wow!

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: A bath?!

Gilmartin: A bath. Cuz I think, like, that’ll be romantic. Oh, and as soon as it came out of my mouth—

Tompkins: Just so I know, just so I know, you show up at her apartment—

Gilmartin: She, she had been, uh, uh, uh, emotionally upset about something. I can’t remember what it was. But she was, and I was like, “I’ll be right over.” You know, “I’ll cheer you up.” I wrote a little poem for her. (laughs)

Tompkins: Oh….

Gilmartin: I read it to her. It’s so, it’s so—and she was too nice to show the real horror she should have reacted to me with. But, it—the reason I bring that up is, is to compare the notes of you don’t—it, it comes out of nowhere because you think, ‘Well, yeah, it’s one out of hundred, but I gotta try.’

Tompkins: Yeah. Well, there’s also that, that—we’re so conditioned to think that’s what’s going to turn everything around. If I just—If I, if I make this a cinematic moment, it will become one, you know, I just, I just gotta open the door to, you know, what would somebody in a movie say? And then, the other person will have to respond like a person in a movie. Not like in real life.

Gilmartin: Which I also think, uh, artists and, and, depress-depressives, may be a little bit more prone to, because our sanctuary is often grandiosity.

Tompkins: Yes. Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Because your mind—you, you retreat into how you would like things to be as opposed to dealing with the way things are.

Gilmartin: Yeah, and if you can paint them any way, and you’re creative, oh my God. So you wind up with these crushing, awful moments where you don’t know it’s grandiosity, you don’t know that it’s—you look ridiculous, until those words come out of your mouth. And then you’re standing there going, “I’m gonna let myself out.”

Tompkins: (laughs) Almost better to have no imagination.

Gilmartin: Really!

Tompkins: Then you wouldn’t get yourself into a situation.

Gilmartin: In many ways, yes. So, uh, so go ahead.

Tompkins: So yes. So we—our relationship, uh, limped along in this very awful, uncomfortable, awkward place for a good, um, couple years, I think.

Gilmartin: And you were seeing each other as friends frequently, infrequently, once a week, twice a week?

Tompkins: Oh, we saw each other, we saw each other very often, um, through her, um, having relationships, you know.

Gilmartin: Did that kill you?

Tompkins: Oh, of course, absolutely it killed me. Devastating.

Gilmartin: Is there anything worse than, than being in love with somebody and having to talk to them about somebody else, and pretend that it isn’t—

Tompkins: I mean, we did not, she did not bring up her boyfriends, she would not like, like rub it in my face. She wouldn’t try to like, you know, use it as a thing to—I have to say, she was never cruel about it. She was never cruel about it. And I—and it’s only now, you know, with, with the distance of time, and, and with maturity and having worked on myself, that I can admit how uncomfortable I made things for her, you know.

Gilmartin: Do you still feel foolish when you see her?

Tompkins: Oh I haven’t seen her in forever.

Gilmartin: Oh. Ok.

Tompkins: We stopped being friends about, um, a little over ten years ago. It’s been almost twelve years. It was, it was after—you know, after 9/11, when a lot of people were kind of taking stock in their lives and saying, ‘Maybe life is too short for this kind of bullshit.’ You know, it was not long after that. We, we, we were working together on something. We were writing something together, um. I gotta say, even despite, the, the, the uncomfortable nature, uh, o-o-o-of our friendship, uh, um, at that point, we were still able to kind of work really well together and create something that was, um, really funny. Um ….

Gilmartin: And all your sketches were about unrequited love. And the guy, and the guy’s a real catch and she can’t see it.

Tompkins: We had, we had written this thing where we played a couple, you know, um, it was this absurd thing where we were this absurd married couple, you know. Um, uh, but, uh, uh, that was—it was that close proximity, um, a-a-and—i-i-it—that—it was the working relationship that enabled the, uh, the friendship to end. Because it was the frustrations with the working relationship, um, that, that really—like, she was able to see and admit, uh, that, that was really just masking, or, you know, that was standing in for this horrible, dysfunctional relationship that we had that really needed to end. Because it wasn’t going to get any better. And, you know, she had told, um, friends of ours, um, mutual friends, um, that she, um, she knew that, um, I was always gonna hold it against her, that she did not return my feelings. And, of course, like, at time, I was like, that’s absurd. I knew immediately that it was the truth. But I could not even admit that to myself. It was like, you know, when you, when you, when you have an unpleasant thought that you really need to focus all your attention on and you look away from it in your mind, you know.

Gilmartin: I can handle that I’m unloved, maybe, but not unloved and petty.

Tompkins: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: You know what I mean (laughs)?

Tompkins: Cause it was, like, a deeper truth that, ok, if that’s true, then what do I do? You know what I mean? So I, I then, I got super depressed. And, and lapsed into this, um, state where, you know, still going out and doing the things that I used to do but, uh, just totally morose, just kind of just there, going through the motions, you know, um. And I was absolutely devastated. Like, I—cuz I knew I had made this happen. I knew it was never gonna get any different. I didn’t know how to be. Like, well, if I, if I run into her, which I would from time to time, do I, uh, ignore her? Do I try to engage with her? Uh, I-I could never get to place, uh, to a comfortable place with it.

Gilmartin: Were you that other people knew about it and were talking about it?

Tompkins: Absolutely. That’s all I thought about.

Gilmartin: So you thought I look not only a fool to her, but I look like a fool to everybody. I look desperate. I look unlovable. I just look ridic—everybody—my rejection is on a billboard.

Tompkins: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: It’s the worst feeling in the world.

Tompkins: It was horrible. It was really horrible. And just being a, a raw nerve for a really long time. And then—so that went on for a good—almost a year. Almost a year after that was when I went to therapy for the first time.

Gilmartin: Now before we get to that, was, was your comedy at this time, was it, uh, was it reflecting that pessimism and that anger or was it—

Tompkins: Oh absolutely, yes. And it was—my comedy at that time was um, uh, was very, like, I-I-I would go up at, uh, a place like, uh, Largo, her in Los Angeles, which was a, you know, a hip, cool room; and I would go out there and I would make fun of, um, you know, other people in show business. I would be really acerbic about, you know, just anything, um, you know, trying to, trying to achieve some kind of uh, er, coolness in the eyes of other people. Trying to get some kind of stature back, you know. Um, I-I did not—I was not able to talk about what was actually going on in my life. I—it was not funny to me. I couldn’t think of a way to make it funny. I couldn’t even talk about it obliquely, um, because, I just—I couldn’t even—I didn’t even know how to think about it, you know. Um, I was not at all in touch with my feelings really, you know. Um, so I was very—uh, there was a bitterness that was coming out of me, um, that was directed as these dumb targets that did not matter, you know. Um, t-t-to the point where, um, I think it affected my, um, my career. Where I think that, uh, I was talking shit about, uh, people or things that, um, I should not have talked shit about. And I think it adversely affected me. There’s one instance that I, I know for a fact, you know, that it took years to correct.

Gilmartin: Really?

Tompkins: Um, I did an episode, uh, uh, this of, uh, Curb Your Enthusiasm. And, um, it was, uh, great fun to do. Uh, I really excited to be asked to do it. Well, I auditioned to do it. I was really excited to get the job. But to be asked to audition in the first place.

Gilmartin: Sure.

Tompkins: Uh, it—my episode wraps, I’m in, um, trailer, uh, getting changed and, uh, there’s a knock at the door. And it’s Jeff Garland. And he said, “Hey. Can I come in for a second?” He comes in. He says, “Listen, I want to tell you something. You did a great job on this episode and I’m really glad that you did it. And you were really, really funny. And I’m glad that you got the job out of all the people that auditioned for it. And I want to tell you, I have to confess to you that I have been holding something against you for a really long time. That, years ago, I remember seeing you go up at Largo, and you made fun of this guy that I knew. You read a letter that he had written to the booker of the shows at Largo. And it was really mean. And it was really nasty. And I thought, ‘This guy is—who does something like that? This guy is terrible.’ And I would see you make fun of other comedians, and I would see you—and then, one night, you made fun of Curb Your Enthusiasm because there was a clip of you in the pilot and you said on stage that you were embarrassed to be seen in that. You made fun of Larry and you made fun of the show. And I thought you were a mean, nasty, phony person. And so I would see you over the years and then I felt bad that I never confronted you on that. I never said anything about that. And I held this opinion of you inside. And then years go by and you were auditioning for this thing and I thought, ‘Well, maybe he’s OK now, maybe he’s not that same person. Regardless, if he auditions and he’s funny, he should get the job.’ And you were funny and so you got the job. But I realized I needed to tell you this. Because it was unfair of me to walk around having this thing against you and never saying anything to your face.”

Well now I had done enough work on myself at that point that I was like, I can’t he is apologizing to me for holding—

Gilmartin: A grudge. A grudge anybody would have.

Tompkins: A rightful grudge. And, I said to him, “Jeff, thank you so much for telling me that. I really appreciate that, because the fact that you are being honest with me in that way means the world to me. Because i-i-it’s a respectful thing to do. And it’s also a very, i-i-in a way it’s a very caring thing to do.”

Gilmartin: Really, yeah.

Tompkins: Right?

Gilmartin: Yeah.

Tompkins: You know, like, because that means—

Gilmartin: That’s, that’s what men do. That’s what a man does.

Tompkins: It’s what human beings do. Because he is saying, “I consider you enough of a human being to tell you this.” You know. He could have written me off and probably did for a long time. Um, but that afforded me a chance to revisit some bad behavior that, frankly, I have, you know, I cringe when I think about the person that I used to be. And the stuff that I used to say. And the way that I used to treat people. And at that time in my life—when I was all about telling myself, ‘I’m justified in doing this. I’m justified and I-I’m better than, uh, a better person than that guy, so that means I’m an OK person.’ Constantly trying to reassure myself that I was a decent human being. When I was not being a decent human being. And I was not behaving the way I-I-I would like to behave. And I was not doing unto others as I would have them do unto me. Which is the one thing that, uh, I-I have kept from religion, you know. That simple rule. Um, it really just is that fucking simple.

Gilmartin: Do you think it’s possible—for somebody that grows up in, uh, in the kind of a household that, that you did, where you’re just—you’re not given, you know, any kind of emotional feedback that makes you feel like a valid person—I don’t see how it’s possible for you to become a centered person who’s happy with how they are without making those mistakes—

Tompkins: Oh yes, absolutely.

Gilmartin: Without breaking the bank and you having to have that moment of clarity where you say, “I need to—I need to change.”

Tompkins: Th-the way I look at things now is, whatever it is in my life where I have made a positive change, my—I-I always first think, ‘Oh, I should have done this so long ago.’ And then I immediately think, ‘ But you’re doing it now.’

Gilmartin: Yes!

Tompkins: You have to just move forward.

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: You can’t look back forever. Um, you know, it’s—i-if I could, like anybody, so many things I would do differently, if I could. But I can’t. You know. All I can do is try to be, a-a-a-a decent person now, is to try to, to try to treat people well now. Um, even if they don’t treat me well. You know what I mean? And that’s, that’s a—i-it’s gotten—the good news is, it’s gotten easier to do. You know, i-i-it’s gotten easier for me to catch myself in moments of, um, you know, extreme emotion. If I’m, if I’m sad, if I feel like someone has offended me, slighted me, insulted me, condescended to me, whatever, it’s gotten so much easier for me to e-either a moment later, the next day, a week later, whenever it happens, to say, “Hold on a second. What was that person going through? W-w-what’s their—what’s their story? And how much empathy can I engender for this person?” Can I really—a-and sometimes, it’s fucking hard. Sometimes it’s really hard. But sometimes, even if it’s hard, I’m able to say, “This person is a person. Just like me.” And thank God I have all that negative example of myself to look at and say, “Well, do I want to be judged forever on the person I was in 2002? Do I want to be judged for behavior that I exhibited last week? Or do I wanna get better, always keep getting better, and always strive to become, um, a-a-a person that I can, that I can personally be proud of?” You know, and say, “I’m not such a bad person.”

Gilmartin: Would it be fair to say that you wouldn’t be doing the comedy that you’re doing right now were it not for therapy?

Tompkins: 100%. A-as I improved my own life, my outlook, m-my art changed. And for the better.

Gilmartin: Oh, absolutely.

Tompkins: You know, I feel like it got—I got—I realized thr-through therapy, man, I have not been taking anything in my life as seriously as I should be taking it. And I have not been—I have been blinding myself with booze, with, uh, you know, with checking out, you know, as much as I can, and telling myself who I am as opposed to finding out who I am. Does that make sense?

Gilmartin: I-It does make sense. And, and sometimes what we think is a disaster is the necessary path to what we want, it just has to circumvent through maybe hitting a bottom, maybe experiencing s-some pain, that give us—there’s so much clarity that can be had through looking at our pain and all the stuff that we don’t want to look at. A-a-and it almost seems like o-our—the worst thing that could happen for us is for us to be given what it is that we’re fantasizing about at the time that we’re fantasizing about it. Because we wouldn’t be able to handle it.

Tompkins: Yeah. What I realized—when it kind of dawned on me—uh, there’s always something more that you’re gonna want. There’s never—because, there’s—I think especially—I think this is true for everybody, but I think especially in our business, because we have these, um, there’s, there’s, um, there’s always a carrot a-and the stick always gets longer, you know. It’s always like, well, OK, you got this, but what about this, you don’t have this yet. You know, and we keep thinking, like, you know, right now, what I would love more than anything, uh, is to get a steady gig on television, you know, where I go to the same place every day, Monday through Friday, um, and I get to come home and have dinner with my wife, you know, at the end of the day. I would love that, absolutely. And (laughs) in my mind, I conditioned myself to think that is a modest goal. You know what I mean? Like, I don’t want to be a global superstar, all I want is my own television show. Is that asking for so much?

Gilmartin: Financially and creatively rewarding, right near my home.

Tompkins: Exactly. Now the thing is, that is, that is a somewhat attainable goal. It’s possible that that can happen. It’s not probably, you know what I mean? I-i-it’s—nothing i-in a weird world like this is probable, it’s only possible.

Gilmartin: What do you, what do you define as the difference between a goal and a fantasy? How do you know when one—

Tompkins: I think a goal is something you can actually work to achieve.

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: You know?

Gilmartin: That’s, that’s what I would say. I would say a goal is something that you can logistically say, “Here are the steps it would take to get to it.” A fantasy is often something where there is a leap of logic there that no blank can be filled in, except by the ego and maybe, maybe grandiosity.

Tompkins: I think any time we’re thinking, “If that guy would just die, then the path would be clear.”

Gilmartin: If only the heads of all the networks could see me tonight, having this show that I’m having.

Tompkins: Exactly. Yeah.

Gilmartin: It would all turn, it would all turn around.

Tompkins: But I think a goal is also something that you—the difference between a goal and a fantasy is a goal is something that you could achieve, but if you don’t achieve it, it’s gotta be ok. Does that make sense?

Gilmartin: Yeah, yeah.

Tompkins: It’s like, look, I, I, uh, I went through a period of bitterness not that long ago, where I was in a, I was in a really dark place. I-i-it was all about, um, you know, uh, entering into middle age, turning—getting into my 40s. And getting, like, I’m 43 now. So, realizing, like, well that’s just going to continue happening. That’s—there’s not—I’m not gonna wake up and, like, “Oh, you’re 38 again.” What? Fantastic! I didn’t know it could go the other way! Um, you get, like, a reset of a couple years. Um, so, I, I, I got into this, this place where I was just overwhelmed. And it, it was, like, it was so much, like, what I bet my mother experience where it’s like, holy shit. Time is going by so fast, so fast, that all I can think about it, ‘I’m almost dead. I am almost dead and where am I and what am I doing?’ You know, I did not realize how great my life was. I couldn’t see it. And I tried—I was trying to see it. You know what I mean? Like, at this point, I am a married man, I’m a professional standup comedian, uh, I’m having, like, a really good year financially, from all these different things. I’m working on, um, all these other projects that are towards my goal, but I was still at this point where everybody else was doing better than I was. I was, I was not any closer to achieving this goal that I wanted to achieve. It was never going to happen. And, but really what it was about was mortality. It’s that time is too short. It’s never gonna happen. And, uh, I-I-I—it’s embarrassing, that I can’t, um, uh, provide for my wife better. It’s uh, it’s embarrassing that I have, I have fucked up my career with this dumb behavior in the past, that now I’m never gonna be where I wanna be, not even what I want to be, but to a point where, uh, I can breathe, you know. It’s always gonna be like this. I’m always gonna be on the fucking hustle. I’m always gonna be traveling around, I’m gonna be packing that goddamned suitcase.

Gilmartin: That’s so crazy.

Tompkins: It was terrible. It was terrible.

Gilmartin: Because I can tell you, Paul, from—you’re—as a peer of yours, and I know there are tons of other peers that feel the same way, we look at you and think, “If I could only get to where, where ….” And that ladder, I think, never ends. Unless you can say I’m happy to just be on this journey—

Tompkins: The ladder never ends because you’re always building the fucking ladder.

Gilmartin: Yeah.

Tompkins: You’re always adding the rungs on there. It’s always you, you know. Nobody else was telling me, “Paul, you know you’re a failure, right? You know that, uh, you should be a lot farther along.” I was the only one telling myself that.

Gilmartin: Do you ever stop sometimes, uh—

Tompkins: Paul, I’m sorry, I do wanna say this. The life that I’m leading now is the exact same life that I was leading when I was in that horrible place, except now I see it all totally differently. And I see how great it is.

Gilmartin: And do you think i-it was anything other than, than therapy that brought—and time, that got you to that place?

Tompkins: I’ll tell you exactly what it was. It was—th-the breakthrough for me—

Gilmartin: Dianetics?

Tompkins: (laughs) Yes. Thank God we can talk about this now. Hail Xenu. I have a book I’d like to pass along to you.

Gilmartin: (laughs) I don’t even know what Xenu is.

Tompkins: Soon you will. Uh, I, I was going to therapy this whole time. I was talking to friends, I was talking to my wife, you know, who’s—my wife is so great. She, like, that she was able to be there for all of that. It was bad. And I was in a bad place. And it was hard on her. And I know how hard it was on her. And she was a fucking champ through all of that. I-I-I ….

Gilmartin: Do you think it’s because she could see the real you inside there and this was just something you had to work your way through—that this wasn’t—it wasn’t that she had low self-esteem, and this was what sh-she was gonna have to put up with for the rest of her life, she knew this is Paul growing.

Tompkins: Yeah. Absolutely.

Gilmartin: Isn’t that amazing? When life gives you somebody that has that kind of patience, and can see into you, and allow you to be that person, and forgive you, and put up with your shit.

Tompkins: Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. She, she—oh, I will say this and then I would like to talk more about how great my wife is. She, um—the thing that, the thing that changed it for me was, I had dinner with a friend of mine, an old friend of mine. And I hadn’t seen him in—

Gilmartin: His name’s not Andre is it?

Tompkins: What’s that?

Gilmartin: Andre?

Tompkins: (laughs)

Gilmartin: Dumbest joke ever. Maybe dumbest joke—thirty-some-odd podcasts. I don’t know why I don’t just shut my fucking mouth. I’m creating wreckage as I do the podcast about wreckage, I’m creating more wreckage. So dumb.

Tompkins: It was not, it was not Andre. Um, we—I hadn’t seen him in a while. And this was a guy who was a-a-a-a slightly older friend, slightly older than me, um, uh, and a guy who, whose counsel I, uh, put a lot of stock in. Um, whether I agree with him or not. He is a great sounding board, and a, uh, uh, uh, a great giver of advice. Not a lot of people are. Not a lot of people give good advice, and give it well, you know. He never, ever, ever starts anything with, “You know what you gotta do.” It’s always—he’s a very, uh, a very thoughtful person in every sense. And, so, we’re gonna have dinner just to, like, catch up. And …

Gilmartin: This is how long ago?

Tompkins: This is like—this is around the beginning of the summer, I think. This year. And he—I think the just asked me, “How is everything?” And I started talking, and I started saying all these things that I did not know I was going to say. And I laid it all out for him. Here’s where I am right now. Here’s this, this, uh, pit that I am in, that I cannot fucking get out of, you know. And he was just able to talk to me in a way to—that flipped my perspective. Because he was saying, “No, you don’t understand. You’re saying this is a bad thing and that i-it’s a dead end and it’s going nowhere. I would like you to look at it as an opportunity for this. Here’s what you could get out of it.” I was doing this—I was gonna do this project, and this thing is going nowhere. I’m gonna bail on it, I’m gonna bail on it. He goes, “Don’t do that. Because as flawed as this project is, if you are good on it, if you give it your best effort, everything will come around to you. Because you are going to shine. You will—i-i-it’s not a matter of, um, it’s not the thing that you want it to be. It’s that you’re getting a chance to do something that, uh, is good for you, you know.” It was just that, it was just that simple.

Gilmartin: Stop obsessing about the whole and just look at what you have control over.

Tompkins: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But he was also kind of making me realize things are not bad. Like, you think they’re bad, they’re not bad.

Gilmartin: It makes me laugh to think that you would have anxiety about your career.

Tompkins: Aw.

Gilmartin: Which tells me it never ends, unless you decide to say it ends. I’m gonna appreciate where I am this very moment in my life, look at what I have and what can I be grateful for, and accept the fact that life is not perfect, and I’m never gonna get what I want, because my brain is crazy. Everyone’s brain is crazy in terms of coming up with, with what they want and where they think they should be.

Tompkins: If you just keep getting everything that you want, th-there’s going to be—

Gilmartin: You’re gonna go mad. You’re gonna go mad. You’re gonna become Howard Hughes and then you’re gonna fear bugs, you’re gonna want things that aren’t possible.

Tompkins: I’m already afraid of bugs.

Gilmartin: Afraid of germs.

Tompkins: You mean listening devices?

Gilmartin: Yes.

Tompkins: That was, that was the beginning for me of the process of-of-of crawling back into the light, as it were. And not long after that, I talked about it on stage. Cuz I do this live show at Largo every month.

Gilmartin: It’s such a great show.

Tompkins: You did it up in San Francisco.

Gilmartin: Oh, I had so much fun doing it.

Tompkins: Please do it again in Los Angeles. I’m putting it out there on the podcast.

Gilmartin: Oh my God, I would—

Tompkins: I would love to have you back on.

Gilmartin: Jump through hoops to, uh, to come to that.

Tompkins: Consider them jumped through. I, so I do a new monologue every month, brand new material, and, uh, which is usually decided that day. I kinda sit and think, ‘What am I gonna talk about?’ You know, and all I could think of was this place of bitterness that I had been in. I was like—but I didn’t wanna—I was afraid to talk about it. Because I thought, like, ‘This is gonna bum people out. I don’t know if I can make this funny.’ But, that’s how I approach it every month, is, ‘I don’t know how I can make this funny.’ And what makes it funny is, it has to be funny because I’m out there in front of people. So it’s the necessity of that, it’s like, you know, the tightrope, you know, make it—it’s gonna be ok because it has to be ok. So, I was like, ‘I wanna try this. I wanna try doing this and see I can make this funny. If I’m ever gonna do it, it’s gonna be in front of these people, who are gonna be the most generous and welcoming people.’

Gilmartin: And these people show up specifically to see you. They love you, they know your point of view, your sense of humor. They show up for that, yes.

Tompkins: They know the score. They know the score.

Gilmartin: This isn’t just a random comedy club audience that has shown up for funny night, and you’re the guy. No. They—you have a built in audience, 300 people, or however many come to Largo—

Tompkins: And there’s some people that might be coming for the guests that I have on the show. There might be some people that are coming cuz their friends won them over.

Gilmartin: They won them over already, is my point.

Tompkins: Yes. Yes, i-it’s a welcoming atmosphere and i-it’s like, if I was ever gonna do this, it’s gotta be now, and it’s gotta be, it’s gotta be tonight, you know, in front of these people. And it was, um, very, uh, uh—and the whole show, I did not realize, the whole show took on this tone of catharsis, of talking about this stuff. And when I was talking about it, I was saying, “I know that I’m crazy.” Like, as I was saying, I’m feeling this way, and I know that, like, intellectually, I know things are not bad, but this is what I’m doing. I’m taking everything that is good, and I’m turning it into a negative thing. So if somebody says, “Hey, you got asked to guest star on that TV show.” It’s like, “Yeah, but I don’t have my own TV show.” You know? And—there’s—and knowing that there’s people in the audience who would love to have the career that I have, and that night, on Twitter, like, there were, there were many people who said to me, “Hey. What you did was really cathartic for me. You talking about that stuff made me feel good. Because it made me realize that I do the same thing. Like, things are good, but I bemoan that they’re not what I, what I fantasized them being, or what I wished them to be.” And then there are people that thought it was just complaining, like, they said, you know, “Listening to you, like get up there and, you know, cry.”—

Gilmartin: But you said you were crazy.

Tompkins: I know, it doesn’t matter. Because they’re in their own thing, you know what I mean?

Gilmartin: Yes

Tompkins: Like, they, they hear nothing but me complaining. They don’t hear the disclaimer. They don’t hear the, “I know that what I’m saying is nuts,” you know. Um, and then my friend was there at that show, the guy who started th-th-th-the about face for me. And he was really bummed out by it. And he said, “It really distressed me to see you talking in that way, and I would hope that for your next show, you would go back to being delightful for the audience. Because people don’t wanna worry about you when they go to your show. They want to be entertained.” And my feeling—wh-what I did not express to him, because, you know, I—

Gilmartin: Was this the Christmas show wh-where you got the nasty letter from the guy that—

Tompkins: No, no. This was, this was July, I wanna say this was the July show. And then we, we—

Gilmartin: Was that when—was that monologue recorded and available to hear?

Tompkins: It was recorded, it is not available to hear.

Gilmartin: Ok, alright.

Tompkins: I wanna give it, give it some distance and listen to it, to see what it, what it sounds like. Because it was, like—I should not listen to this right away. This is something I should let breathe a little bit.

Gilmartin: Ok

Tompkins: A-a-and, you know, I felt very—he was telling me this, and I felt embarrassed, you know. And I felt like, oh, I fucked up. O-o-or I displeased this guy, who is not, not quite a father figure to me, but, certainly an avuncular figure in my life, you know what I mean? Or, maybe a big brother in a lot of ways. And I think—but a guy that definitely has a presence in my life that, I don’t want to disappoint this man, you know. Um, but I was also, I was frustrated because, like, that’s not what it was, you know. A-and, I feel like the, the difference between the entertainer and the artist is that, that the entertainer, the first duty of the entertainer is to entertain. But the first duty of the artist is truth. And you—and I like to consider myself an artist. And I-I feel like my evolution as an artist has not come all this way to just stop at merely entertaining people. I’m not trying to shut anybody out, I’m not alienate anyone, but I do feel like it is pointless for me to not explore these things.

Gilmartin: Absolutely.

Tompkins: It’s pointless to me. T-to have this much feeling and not, like, explore that ever? Ever?! Like, I gotta try it. I gotta try it.

Gilmartin: To me, that’s the most fertile ground for art, is that makes us uncomfortable, that is tinged with tons of gray, where things aren’t clear, and especially where there’s the disconnect between what we know intellectually and what we feel emotionally, because it’s so, it’s so crazy. It’s like, it’s like, how can I know something intellectually and still feel different emotionally? How do you not talk about that artistically? That to me is, the—that’s what a great movie is about. Like, Broadcast News, for me, what is so great is that Holly Hunter falls in love with William Hurt, who she has no respect for. And she can’t understand why, why do I love this guy? Y-you know, that to me is, is great art. So, I say bravo, sir!

Tompkins: I accept your kudos.

Gilmartin: Uh, well if, if you live in the LA area, and, uh, you’ve never heard of, uh, of Paul Tompkins: a) You’re an idiot, uh, b) Get to his monthly show—

Tompkins: You’re stupid for not having heard of me.

Gilmartin: Uh, you probably have—were raised in a loveless household, and, uh, there’s hope for you, if you can only ask out a woman who has no feelings for you. You’ll get your moment of clarity. Um, uh, the Paul F Tompkins—what is the name of the live show?

Tompkins: The Paul F. Tompkins Show.

Gilmartin: Ok. And the podcast is The Pod F Tomkast, and, uh, you can get it on iTunes, you can go to the website paulftompkins.com, follow him on Twitter. Um, anything you’d like to plug, other than before, uh, because we’re at like, an hour and eleven and I know you got, uh, you got some places you, uh, you gotta go.

Tompkins: Wow. Um, two things in December. Uh, I think it’s December 15th, I believe, is my Christmas show at Largo, which will be a benefit for Habitat for Humanity. I’m sorry, December 17th.

Gilmartin: December 17th.

Tompkins: December 17th at Largo, um, December 22nd I’ll be in Charleston, South Carolina, which is where my wife is from, and this is the first I’m performing there, I’m very excited.

Gilmartin: Oh, nice!

Tompkins: That’ll be December 22nd. It’s a benefit for Crisis Ministries, which is a local charity there. So, um, I hope to see people there.

Gilmartin: If you for that giving to the needy kind of bullshit.

Tompkins: If that—look, if you want to pretend to feel good about yourself, here’s how you can do it.

Gilmartin: I’ve got a charity called Looking Out for Number One that, uh, I’m just getting off the ground right now. Well, how about if we—you know what’s funny, before, before, uh, we did this, uh, this episode, I said, “Paul, there’s this idea I have, uh, where I’ll start, uh, my guests and I will start giving, uh—answering advice questions and we’ll do it—we’ll call it Either/Or.” And, uh, the first one I was going to do is this email I got from this woman, and she says, uh, “There is something wrong me because I love a dysfunctional man incapable of having a deep relationship with anyone and I don’t know how to stop or break away. I don’t understand why I can’t. I don’t know why I always love men that are incapable of loving me back.” How perfect is that?

Tompkins: That is perfect.

Gilmartin: Also, how common a thing is this? So common.

Tompkins: I think most of us go through this, where you’re trying to, you’re trying to get—there’s some person that you’re making all these other people stand in for. For how long, you know? And I think it’s—so many people I know, it’s the, it’s the pattern that they go through for a while until they eventually break in one way or another, you know. And start another nice relationship with somebody nice.

Gilmartin: Yeah. I-i-it—I like to think of it as it excites the unhealed part of you. And when you heal that part of you, you will be shocked at what used to excite you about people.

Tompkins: It’s just so much better.

Gilmartin: And so much easier to live—th-that woman’s name was Winter. So, uh, Winter, uh—

Tompkins: Ooo, I like it.

Gilmartin: Uh, hopefully, you’ll, you’ll get to that place where you, you know, you work on yourself and can, uh, you can stop chasing guys that, that aren’t interested in you. But know that you’re, uh, you’re certainly not alone, um, in that one.

Tompkins: Not at all.

Gilmartin: And, uh, Paul F. Tompkins—

Tompkins: We’re not gonna do a fear-off?

Gilmartin: Oh, yeah, I almost forgot the fear-off!

Tompkins: Why did I bring it up? Why did I just do that?

Gilmartin: No, I could talk for another 45 minutes, but I know you got an appointment, so, uh, yeah, we’ll do a, a quick fear-off. Cuz you said you only, you have, like, five major ones and they all kind of, are sub, underneath that.

Tompkins: Yeah, branches, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gilmartin: Let’s get to the—what are your trunks, your fear trunks?

Tompkins: Uh, still, that I may never achieve a relatively stable, comfortable existence in my career.

Gilmartin: I fear that, uh, my depression will get the better of me and my purpose in this will be to show, uh, to show other people how serious depression is.

Tompkins: Um, and this that yours or is that—

Gilmartin: Yeah. No, these are mine. I came up with some.

Tompkins: Oh, I get some personal ones.

Gilmartin: You get some fresh ones, from the fear stash.

Tompkins: From the personal fear cellar. Uh, I fear that I will drift away from my family.

Gilmartin: I fear that our foreign policy will trigger a world war.

Tompkins: That’s a pretty good fear.

Gilmartin: Yeah.

Tompkins: I fear that I will let my wife and my marriage down in an irreparable way.

Gilmartin: Uh, I fear that we will never get enough elected officials in office to stand up to special interests.

Tompkins: I’m less afraid of that than I used to be. I have to say.

Gilmartin: Where’s that hope, where’s that hope coming from?

Tompkins: With the Occupy movement, honestly. The fact that it’s still going on and that it’s still spreading, um, actually, gives me a lot of hope. That it’s finally kind of happening, that people are, uh, are literally getting out on the streets, you know. Which is what I think needed to happen.

Gilmartin: It’s certainly what needs to—how it needs to, how it needs to start, at least.

Tompkins: I don’t want to be cynical about it, you know. And I think some people were, were pretty cynical, obviously, there are still people who are cynical about it, but I saw people that were cynical about it when they first heard about it, like, “Ugghh, no, like hippies and bongos and stuff.” And people that were not supposed to be cynical about it, you know. But it’s like, these people are like, they’re like you, you know. And now there’s the people—those are the people that are going out there, you know, friends of mine that are—that are out there, you know, New York and LA. So, yeah, I’m less afraid of that than I used to be. Um, I’m afraid that I am a (laughs)—that I do not realize what a thoughtless and self-absorbed friend I am to my friends.

Gilmartin: Uh, I’m afraid I will execute badly, fail to enjoy, not put enough effort into, or just plain stink at a project I’m going to do.

Tompkins: I’m afraid that I am not as talented as I think I am or that people tell me I am.

Gilmartin: That’s so funny, because my next, my very next one is I’m afraid I’m a much worse actor than I think I am.

Tompkins: I think I found out that I am recently.

Gilmartin: You think you’re not a good actor?

Tompkins: I’m think I’m ok, you know what I mean? I-i-it’s the equivalent of, if, like I was a singer, uh, I could carry a tune. You know what I mean? Like I can reasonably pretend to be somebody else but, um, I know that at things like auditions, uh, that I-I realize sometimes, uh, like, I’m not, like, I’m just ok at this. Like, this is, this is an audition that a real actor will, will ace.