Episode notes:

Paul: Welcome to episode 114 with my guest listener Michael D. This episode is brought to you by Squarespace, the all-in-one platform that makes it easy to create your own website. For a free trial and 10% off, go to Squarespace.com and use the offer code happy. My name is Paul Gilmartin. This is the Mental Illness Happy Hour, 90 minutes of honesty about all the battles in our heads, from medically diagnosed conditions and past traumas to everyday compulsive, negative thinking. This show is not meant to be a substitute for professional mental counseling. It’s not a doctor’s office. It’s more like a waiting room that doesn’t suck. The website for this show is mentalpod.com. Please go there and check it out. There’s blogs written by me, by guest writers, there’s a forum you can join and post in, there’s tons of surveys that you can take that I’ve designed that lets me get to know you guys and what’s going on inside your heads. So, yeah, please go check that out.

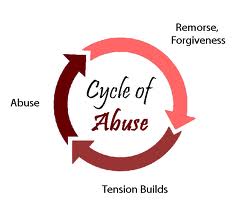

Let’s get into the show. You know, it’s interesting last week’s show I’d read a letter where somebody had wanted—a listener had wanted to hear more from the episode with social worker Ray, they wanted to hear him talk more about the cycle of abuse in families. And we didn’t really get to it in that episode, and as I was putting this week’s episode together, it’s just fortuitous how so many of the, like, emails and survey responses and this episode with listener Michael D., the subject of the cycle of abuse just happened to come into play. I just love when that happens on the podcast, when there’s this beautiful synchronicity.

Ok. Kick it off with a couple of surveys. This first one is from the Shame and Secrets survey filled out by a listener; it’s a guy who calls himself James. He’s gay, he’s in his 40’s, was raised in a pretty dysfunctional environment. He writes, “My mother was/is extremely controlling and probably has a few personality disorders: borderline, narcissistic. My father, who is now deceased, struggled with depression. I never really knew him because he rarely spoke to me. I felt very alone as a kid and didn’t have many friends until I discovered drugs and alcohol in my late teens. My mother used to strap me with a leather belt when I was bad and threatened to leave welts that would never heal. She would punch me in the face and call me ‘faggot.’ She used to sleep in my bed at night for years because she didn’t want to have sex with my father. She used to tell me that and I remember feeling very creeped out about it. And yet, I have always loved my mom. We still live together and I take care of her in her old age.” “Ever been the victim of sexual abuse?” He writes, “Some stuff happened but I don’t know if it counts as sexual abuse. When I was 12 years old, my mother sent me to ‘aversion therapy’ because she was concerned I was growing up to be homosexual. For one year I met with a doctor recommended to my mom by our parish priest, who made me watch slide shows of men and women in various states of undress. And gave me electric shocks to my fingers every time a male was shown. I would also have to smell test tube vials which would be associated with either men or women. Female smells included rose, cinnamon and vanilla. Male smells were shit, bleach, and gasoline. My therapist would show me pictures from true crime books of murder scenes and explain to me that this was how gay men ended up dead. This experience was pre puberty. I didn’t know anything about sex at that time. I grew up to be a gay man who is unable, even after 17 years of therapy, to have a normal sex life.” “Deepest, darkest thoughts?” “Even though I want to be social, I fear that people see something in me that is frightening or offensive so I rarely leave home. Despite my self-loathing and anxiety, I still managed to meet a wonderful man who loves me deeply, yet in eight years I’ve never been able to ejaculate with him because I feel so much shame and repulsion towards my sexual needs.” “Deepest, darkest secrets?” “When I am happy, I feel guilty. When I feel guilty, I have to mentally punish myself. I am terrified of violence and death but feel compelled to watch disturbing shock videos on the Internet. War, atrocities, animal violence, suicides, hate group propaganda. Afterwards I feel gutted and afraid to go to bed. I wake up in the middle of the night with severe panic attacks.” “Sexual fantasies most powerful to you?” “My sexual fantasies revolve around being rejected. I masturbate thinking about my boyfriend cheating on me and I can actually feel the hurt inside my body, which brings me to orgasm. I have fantasies of men using me, almost as enhanced masturbation. I’ve never fantasized what it would be like to enjoy receiving sexual pleasure from someone.” “Would you ever consider telling a partner or close friend?” He writes, “Yes, I have spoken about all of this with my boyfriend and also my psychiatrist. He accepts me completely. I am so lucky. Despite my past, I have such a warm and affectionate lover.” “Do these secrets and thoughts generate any particular feelings towards yourself?” “I feel disgusted with myself. I cannot look at myself naked. I am terrified of confrontation. That said, I keep going. I have love in my life and I have amazing long-term friends, a comfortable home, and a dark sense of humor.” James, of all the people that I have wanted to hug in the 2+ years of doing this podcast, you are at the top of the list. That survey moved me so deeply. I’m so struck by your fortitude. It’s—God I can’t imagine going through that aversion therapy stuff that you went through. How that must have—buddy, I’m sending a lot of love your way. But it sounds like you’ve got some love in your life and our partner sounds like a great, great person.

And before we go to the interview I just want to read a Happy Moment filled out by a listener named Amanda. She writes, “A happy moment was a recent late morning on a Saturday as I was driving back home after running some errands. The temperature outside was a perfect springtime cool. The windows were down and there was a slight breeze in the car because of it. Sunshine of My Life by Stevie Wonder was on the radio. The sunlight looked beautiful. The street I was driving on was nearly devoid of traffic for a long stretch before the stoplight in the distance. And I just felt connected and free of any worries. No anxiety. No physical pain of any sort and good memories associated with the song. Simply wonderful.”

[SHOW INTRO]

Paul: I here with—we’re gonna call him—we’re just gonna use his first name: Michael.

Michael: Yeah, yeah.

Paul: You’re cool with that, right?

Michael: I’m cool with that, yeah.

Paul: We were talking before we started recording that there are some people involved in his story that are still kind of in the middle of things that are, you know, it would just be simpler that way and kinder to them if they weren’t dragged into what we’re gonna talk about. So that’s—otherwise if it was just about you, you would be comfortable using your full name.

Michael: Yeah, sure, yeah.

Paul: You’re how old?

Michael: I’m 45 this year.

Paul: Congratulations.

Michael: Old enough to not be able to remember how old I am.

Paul: And where would be a good place to start with your story? We exchanged a couple of emails as I was coming up to Portland. There were so many listeners I wanted to record and I couldn’t even get to a quarter of the ones that I wanted to record. And I feel kind of bad about that. And some of it has nothing to do necessarily with what their story is about, it’s just sometimes when I get depressed or overwhelmed, I just have to make a decision. And I have to go, “Ok, this person’s gonna come on this day and then I’m shutting the whole thing down.” Because otherwise I just—it’s—I ruminate about it. Did I make the right decision? Is this person’s feelings gonna be hurt? And I know that nobody that likes the podcast wants me to be stuck in the corner of a room feeling like I’m inept and whatever. So with that out of the way, let’s get into your story. Where’s the best place to start?

Michael: Well the first memory I have is my dad laying dead by the side of the road.

Paul: Good podcast. We’re done.

Michael: Yeah.

Paul: Thank you for coming.

Michael: So I tried to bring strong. So ….

Paul: How old were you?

Michael: I was four years old. And we were on a family vacation in a borrowed pickup truck with a camper shell. And it was …

Paul: What state was this?

Michael: Wyoming or Montana, up there near Yellowstone. And it had been raining and they stopped to get gas. And my dad was driving, they switched out and my birth mother took over. And she spun out in the hail, flipped the car. And I found out recently that my dad died saving me. He threw himself on top of me. And so my first memory is of him laying on the side of the road. Which is probably the most important event in my life, right?

Paul: Wow.

Michael: And my second memory is at the hospital after. So I don’t care for going to the doctor’s office a whole lot. But things went south from there. So that was in July and in October she remarried. Now unfortunately she remarried someone with a lot of problems. And that just went worse from there.

Paul: So the only memory you have of your dad is that memory?

Michael: Yeah. I have a couple of photographs of him since, but I don’t have any memories of him.

Paul: You don’t remember what he was like or any of that stuff?

Michael: Nothing.

Paul: Is there fondness attached to that memory, or is it all bad?

Michael: Oh, no that one memory I had by the side of the road, no, it’s just all traumatic, all sad. I mean sadness is the dominant emotion probably I would say in my life.

Paul: Because I mean the fact that he was trying to save you but you didn’t remember him trying to save you, you were just told that.

Michael: No. Yeah, I found that out most recently. My birth mother’s family is pretty dysfunctional and doesn’t talk about anything. And I’ve had a really hard time finding out anything about my dad. Which I think is kind of weird because it seems obvious that a kid would want to know about their father, to the point where my birth sister’s daughters, my nieces, didn’t even know that she had a biological dad. They just never talk about him. Which is ridiculous, I mean I have a picture of him up in the dining room on the wall of fame, right? And so it was really hard for me because I didn’t have a father and I didn’t have any memories of a father.

Paul: They just assumed you were the child of your stepfather.

Michael: Yeah, a lot of people would say that. And even as a kid I knew that I had to keep up pretenses but I couldn’t let that go by. Anytime somebody said “your dad,” “Oh, no, no. Stepfather.” I mean it was a big point to me even though that was socially—got me hot water. Because that was cracking open that façade.

Paul: Were you not fond of your stepfather?

Michael: No, he was abusive. To give you an example, so my therapist says I have to—

Paul: How many kids in your family?

Michael: Just me and my sister, biological, but then he had four daughters that he brought. And so some of them lived with us, some not. My therapist says on a scale of one to ten, I have to say he was a 13 on the abuse scale.

Paul: Really?

Michael: So I say he never used a weapon, how could it be a 13? But he says it’s not good. I just got used to it. It’s a sensitivity, right? You get used to it. My sensibility for people hitting me is fairly different than most folks. And so they had this delightful game that they would play after dinner. He would go down the hallway, turn out all the lights and hide somewhere in one of the four rooms down there. And then my birth mother would push me down the hall and I’d have to walk down the hall until he jumped out from somewhere and scared me. So you might guess that a small child who’s seen his dad die traumatically might be a little twitchy to begin with. And so this game just—again I thought it was just normal. I didn’t know.

Paul: That he was sadistic.

Michael: Yeah.

Paul: I mean how sadistic to do to a four-year-old who’s scared of shit that’s not even scary.

Michael: Yeah. It’s mind-boggling. And there’s so many parts…

Paul: Did your mother seem to relish it the way he did or was she just controlled by him?

Michael: You know, for many years I thought she was just neglectful. She just had given up and checked out. But the more I look at it, the more I realize that she was actually much more active. And so I’ve had to reconsider that. About two years ago some stuff happened and I began digging a bit more and discovered how the abuse is generational. It pervades my entire family of origin. And so as a result of that, I don’t have any contact with most of them anymore because it just drags me down. I get sucked into it. So I don’t really know—I haven’t—ever since then I haven’t been able to really interact with her to know any more but as I look back on my memories, she was very active. And I can only reinterpret it as not really neglectful. But I think there’s a sadistic part too and I don’t know why. I suspect she was abused as a child. Again I don’t know, I haven’t talked, but since her father was abused and was an abuser, I expect it, so maybe I should have some compassion that way. But, you know, she really enabled his behavior.

Paul: Was he a drinker?

Michael: Not to excess. You know, social, I would say casual drinker. He had rage issues that would explode on the spur of the moment. And it was just one of these things that we never talked about, right? Oh he got so mad that he broke the steering wheel on the car. Oh, ok, he broke the steering wheel.

Paul: Wow, that’s pretty mad.

Michael: That’s pretty mad.

Paul: That’s a hard—I’ve done some screaming and some pounding on the steering wheel and—was he an imposing guy physically?

Michael: Well he was to me because I was always smaller. I grew very slow and so it wasn’t until later in life that I actively began training to defend myself and got bigger than him. But I wouldn’t say—I think he was average height. He just was fueled by rage.

Paul: What did it feel like when you got bigger than him?

Michael: Well there’s actually I remember one incident. I was maybe about 15-16, so this was around the time he tried to choke me, but—

Paul: Also known as your birthday.

Michael: Yes. Happy birthday, would you like to stop breathing? So he had this thing where he would just smack me upside the head for no apparent reason and so I finally got to the point where I was big and fast enough, he went to do it without thinking. I blocked it and returned and slapped him upside the head. And that was the last time he ever touched me. The game wasn’t fun once I fought back.

Paul: Yeah. Did he say anything when you slapped him?

Michael: Nope. Just turned around and walked off. And that was the end of that. It just never happened again.

Paul: I’ve heard that so many times from people I’ve either interviewed or talked to. It’s almost like what they’re doing is—almost like they’re not even aware of it on a certain level and then once that person fights back, they’re—it’s like a switch turns off. It’s like, “Oh, ok, I can’t any more cookies from that jar.” You know what I mean? It’s so—there’s like no intellectual processing of it, it’s almost like a caveman kind of level. It’s fascinating to me how that—and it’s almost like just the very act—like there’s—there never seems a struggle for the control, just the very act of that person putting their foot down shuts that off. And I’m even talking about girls that are, you know, 13 years old that, you know, their father’s molesting them or something and they just take some type of stand.

Michael: Yeah, I think all it would take is just saying no. Saying no I think would have been sufficient at a certain level. The thing that boggles kind of my mind is I can kind of understand, ok, there are certain people who are damaged in that way and they think this is a reasonable thing to for years slap around this kid. But then what goes through everyone else’s mind in the family who says, “Ok. Well, he’s just beating him, I guess that’s ok.” There’s no line there? And no one stands up and so part of what happened two years ago I discovered some people were being actively molested and …

Paul: By him?

Michael: No, not that I know of there. But that’s an interesting part. When I talked to my birth mother, I mentioned there was someone who was molesting people in the family, and she leapt to his defense. And I said, “Wait a second, I never said his name.”

Paul: Wow.

Michael: “Why are you defending him?”

Paul: Really? And how was she related to your birth mother? Or he, how is he related?

Michael: He’s her husband.

Paul: No, no, no, the person who was doing the molesting.

Michael: Oh. That’s her son-in-law. It’s my birth sister’s husband. And so I said, you know, this has to stop.

Paul: This is the husband of the sister you have that was conceived by your stepfather and your mother.

Michael: No, my real dad, my bio-sister.

Paul: Oh ok.

Michael: So it’s her husband. So my nieces. And so my birth mother says, “Well, what are we supposed to do?” I said, “Well, first step you could stab him with a kitchen knife.” Just off the top of my head I’m thinking right out loud here.

Paul: Yeah.

Michael: “I’m just thinking out loud here, but how about you say, ‘No.’ You drive over, you get your granddaughters out of the house with the child molester.” Step one.

Paul: Yeah.

Michael: Don’t even bother to pack jammies, just put them in the car and drive. “Well, that wouldn’t change anything.” “Yeah it kinda would.” So that level—at first I thought, “Well this is an amazing level of laziness.” But then it dawned on me, “No, she herself thinks this is reasonable behavior.”

Paul: Yeah.

Michael: Which means she was probably abused. And—but this is active enabling. So she couldn’t burn calories to protect me as a kid, but she can burn calories to protect her granddaughters’ abuser? This makes no sense to me. This is exactly the opposite of how it should be. Which says somebody’s really, really messed up.

Paul: Yeah, they’re afraid of opening that door of what is right and what is wrong because then they’re gonna have to look at the things that were done to them probably that were wrong.

Michael: So during the last phone call I had with her, I was bringing up some of the stuff and she said, “Don’t open that door. You don’t know what you’ll find.”

Paul: I talked to her. That’s why I told her to come to the door.

Michael: And—I’m sorry if you really did. But she has this thing where I think there’s an instinct, a natural human instinct, that this is wrong. And she knows it’s wrong at a very fundamental level, but she’s so damaged and she so into—after decades upon decades of this—and you know, I think was my dad in some sense a way out? And then she wrecked the car and killed him. And she felt she had no money and she had to move back in with her father who himself was abusive. He beat my grandmother almost to death several times. Drove her into the psych ward at the hospital. I mean just an amazingly abusive person. And so was that experience of I had this one golden ticket, this one way out and I ruined it, did that break her completely? I don’t know. But she’s amazingly warped and twisted and for years I chased this, I wanted a family. I lost my dad when I was four. I had one memory, nothing beyond that. I wanted that family and here is a mother, ok. I needed that maternal energy. I chased it; I chased her approval for years.

Paul: Did she ever give it to you?

Michael: Oh no.

Paul: Was she ever warm to you?

Michael: You know, I have one memory of her smiling when I was a little kid and I actually wonder if it was before my dad’s death because she always worked as far as I knew, and this memory was I came home from the school and she was home from school, and I actually have a photo of when I’m like two and she’s smiling and happy.

Paul: It might have been gas.

Michael: It could have been. I knew the cabbage was a bad idea. So I wonder was she happy before his death? Was she miserable before had a moment of happiness, and then suddenly everything went to hell?

Paul: I’m gonna give you my two cents on that – is people that don’t deal with horrific abuse that’s been inflicted upon them, no spouse is gonna be able—no human outside of yourself is going to—no matter how charming and fun they are, is gonna be able to pull that stuff out of you. They may soothe it or numb it for a while, but that stuff is so deep and so heavy, it’s gonna come back up, you know. I think we can get distracted and I think that’s where a lot of addictions come from, is they’re a way of us not having to deal with things that are confusing or icky buried deep inside. So that’s kind of my two cents on that kind of stuff but you know, yeah, she might have been experiencing the best time of her life, but if her dad was like what you said he was, good God, what kind of child isn’t gonna be emotionally so fucking injured by that?

Michael: Well it’s amazing that when I started digging a little bit and discovered how bad it was, I mean it’s one thing if it happens but when you look back generation upon generation, how do you break that cycle in some sense, right? And so that’s my sacred duty is to break that cycle for my kids, right? It’s not gonna happen again. I tried to break that cycle for my nieces and only time will tell, right? The damage has already been done at a certain level, but I like to think that just the fact of standing up, of saying, “No, this is not acceptable,” maybe after some work, some years of therapy, they’ll be able to see, “Ok, this is abnormal. This is not what we have to do, to continue to perpetuate the thing.” However the mind just kind of boggles at it. I can’t put it any other way of how this family could possibly hang together for these generations with this amount of work. I remember when I was in college, still way deep into my stuff, not being able to talk about it, late one night. And when I just was struggling and had a breakdown or something, and I said to a buddy of mine, “You know, you can’t just make one TV movie about my life, you could make a bunch of them.” And I didn’t realize when I said that, that that was a bad thing. I was just making an observation. And I think everybody around me could tell that I was struggling, but without really some hard work, and I mean a brilliant therapist, and a decade of work, I was not able to get out of that. I mean, for years and years and years I was in the midst of that. And so I have a certain amount of compassion for somebody who’s in the midst of that because you can’t think your way out of it.

Paul: No, and it’s so overwhelming and it’s so deeply ingrained. It’s almost like trying to change your breathing. It’s such a part of you and it’s so—my therapist said family dynamics are like—you know that mobile that hangs above a baby’s crib, and if you like pull part of it off, the rest of it will shift to rebalance itself? And they said that that’s—dysfunctional families are like that and then when you change one dynamic like you, you know, you pull love out from the father, other things are going to try to shift to make up for that. But rarely in ways that are healthy.

Michael: Oh no. Well my thing was I had—actually I had a brief respite. I went away to college for two years and it was my first exposure to alcohol, which I made sure I embraced fully. And unfortunately my grades suffered a little bit from it. I don’t know if I attended class much my last semester there, but I was living on campus. And it was the first taste of, well; I shouldn’t say functional families, but non-dysfunctional, right? College kids have their own issues, but wait; nobody hits me here, right? I don’t have this issue of what’s gonna happen when I—

Paul: You weren’t going to the right parties.

Michael: Yeah, apparently not. And so then I basically failed out and had to come back home. And that—moving back into it was probably in some sense worse than the previous.

Paul: Because you had tasted what it’s like to be around people that aren’t abusive.

Michael: Yeah. Now I had a sense of normalcy and I had to get back into it. And so my way of reacting to that was I became incredibly rigid about what I was doing. Everything I was doing – my schedule. I would get up at 4AM to go for a 5K run every day, seven days a week. I would go to work at this time, I would go to school, I’d come back, I’d have dinner, I’d go lift weights. Every day had to be exactly the same. It was this rigidity, it was my sense of control, without knowing what I was trying to do, I was adapting to the situation. And it, you know, caused my mind to just fracture at a certain level. I couldn’t keep it up for very long; I mean I lost probably about a hundred pounds over the course of a year and my body—

Paul: And everybody told you you looked great.

Michael: Yeah. “You look fantastic!” And they would say that thing, right, “Oh, you know, you’re really good now. We used to say you looked good, but you’re really good now. This is better.” And, “Oh, I bet you’re saving a lot of money on food.” Yeah, that was really my big concern is the grocery bill. And I had—actually my boss at work, she said to me, “Are you ok?” I said, “Yeah, I’m fine.” She said, “You’ve lost a whole lot of weight. What’s going on?” I said, “Oh, nothing, just working out, eating right.” And she says, “You need to go to the doctor if you haven’t been doing anything extreme, because this amount of weight loss is not normal.” “Oh yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, whatever, whatever, whatever.”

Eventually your body breaks down and my mind broke down. That level of just white-knuckle, holding on rigidity, and any time anything was out of that order, would, you know, just freak me out. I couldn’t handle it, I couldn’t take it. I was just living on the edge.

Paul: Kind of reminds me of like anorexia, without necessarily the food restricting.

Michael: Yeah, well actually that was there too. I was living on about 900 calories a day.

Paul: And running 5K?

Michael: Yeah.

Paul: A day. That’s …

Michael: Yeah, it’s not even remotely healthy.

Paul: Wow.

Michael: And, uh …

Paul: Did you think you had an eating disorder then?

Michael: No, not at all, right? My whole life I’d been the short, chubby kid. And always heard, you know, “You just need to use a little elbow grease, push away from the table.” So I said, “Oh, that’s the trick? Ok, that’s what that feels like. This thing about being hungry constantly? That’s what you should do.”

Paul: That’s winning.

Michael: Exactly. This is the feeling of winning. I’m gonna lose weight. I remember I’d weigh myself every evening, right, and fanatically watch that number. And if any day it went up instead of down, I was just crushed and devastated. It was a full-on eating disorder. No question whatsoever. But because I had the weightlifting component, people socially thought it was acceptable, right? I mean, I honestly feel like if I had been female and I’d lost half of my body weight over that time period, people would say, “Oooo, Karen Carpenter all over again. Let’s talk to this girl.” But it was like, “Oh, no, he’s just really fit now.” So I didn’t even see it as a sign that something was going on, that this was abnormal. I mean if you talked to me intellectually I could say, “Oh yeah, nobody else gets up at 4AM every day.” My friends would be like, “Yeah, yeah, why don’t you stay around a little longer?” “Nope, sorry, I gotta get home, I gotta get up in four hours.” “You’re a little weird buddy, why don’t you take a day off?” And the thought of taking a day off was just too much, I couldn’t handle it. No, the world’s gonna come apart if I don’t keep to the schedule. And so, yeah, there was an obsessive component to that, I think it was all about control, trying to control this environment that I was back in again and I didn’t know how to get out. Which was silly because I was working, I could’ve just moved out. But for so long they had trained me to be a victim that I just fell right back into that role again. And it was really hard for me to get past that.

Paul: Was there a part of you that felt they needed you, that’s why you were there? Did they guilt you into staying? Were they welcoming to you living at home? What was the vibe of you living there?

Michael: Well, they wanted me to live at home because they could control the story. To make sure that I didn’t say anything to anyone, let loose the secret of what was happening behind closed doors. But—

Paul: You being beaten, your siblings being beaten, anything else other than that or just…

Michael: Well, there was sexual abuse as well as physical and emotional abuse. It was for the most part—

Paul: From your stepfather.

Michael: Yeah, the dim sum platter. You could have a little bit of everything. And, I mean, I remember I got a very creepy vibe from him once but he never made a move on me, thankfully. But I really worry about my sister.

Paul: You never asked them if he did anything?

Michael: No, not since the breakup or the severing of my contact with, I really haven’t. When I talked about it right near the end period there, people were very sketchy but they would never say anything outright. And what really kind of frustrates me, as I started unrolling this, I’m calling all the different people in the family of origin, “Did you know that so-and-so said this happened? Do you know that happened?” And people would say, “Oh, well, yeah, didn’t I tell you about that time that Grandpa told me this incredible story about abusing a prostitute, blah, blah, blah?” “What?! No you didn’t mention, this information seems like it would’ve come in handy twenty years ago, when we could have said, “Man, this guy’s a creep, let’s not spend time around him.” It’s bizarre the things that kind of came up and everybody kept hidden and compartmentalized. And so that’s the thing, is if I was in a house they could control me, they could make sure I was doing what they wanted me to do. I think there was a large part of the role that I took on for myself of protector. That it was my role to stand between abusers and their victims. And even though at that time, it was just my birth mother, her husband and me in the house, I still, I think, I had that role. My job was to get beaten. I was the whipping boy.

Paul: I see, so he had anger that he had to unleash, you should be there to receive it because you can receive it best.

Michael: Yeah, so I guess I can take a punch. So that’s why I was there. And again I’d never thought of this, and I vividly remember about four years into college, I took a psych course. Which was the beginning of the end for them because as I started hearing about dysfunctional families, I’m like, “Wait a second. This sounds disturbingly familiar. Maybe something’s not quite right at home. Even then I wasn’t able to see the role that I was playing. I just, um …

Paul: How did you feel when you saw your family portrait in the psych textbook? Was that weird?

Michael: It was a little bit weird because he never paid me the royalties for it. So, I was hoping. No, it is scary, I think, at a certain point. And so for a long time I just hid behind like my go-to maneuver, which is, “Let’s make inappropriate jokes about things.” And that’s just kind of how I did it, right? I was gonna be that guy that had the bad background, who just laughed about it, ha, ha, ha. It only makes me laugh, the Danny Elfman song, but it didn’t, right? I mean, that was the thing. And it took me years to get to the point where I could recognize maybe there’s a problem here. And it took more and more years before I could talk about it and then in some sense it’s sad it took—such a waste of time because if I’d done almost anything different, you know, I have that feeling maybe it could be different. Maybe I could have made a difference; I could have pushed things onto a different path. Which is itself crazy thinking.

Paul: It’s its own sickness. You know, I think we all do that. I think we all shoulda coulda woulda. And that is such a waste of time to sit and beat ourselves up instead of going, “All right, how am I gonna move forward from this? How am I gonna be the healthiest me that I can be? How am I gonna flourish?”

Michael: Yeah, I think I’m pretty darned good at beating myself up. So it’s—I wouldn’t call it a siren’s call but it is definitely something you have to be aware of before you go down that road again. But then you play the game of, well, what would it have been like? What would my life have been like? And so you go through this standard thing well, how would I have met my wife and had my kids if I’d done something different? So I don’t believe there’s any value in worrying about what could have been. But there’s still that tendency kind of late at night, you know, it’s almost like you have a sore tooth, you can’t help but worry at it occasionally.

Paul: So what was kind of the personal cracking point or bottom for you? Was it those—that period where you were living at home and you were food restricting and over-exercising?

Michael: Yeah, I mean, I remember very vividly, I had what we would call a nervous breakdown back in the previous century. I don’t even remember what it was over, but I’d just come back from lifting and I was in the bathroom taking a shower and I just lost it, broke down, collapsed into a fetal position on the floor sobbing uncontrollably. And I was there for hours until they came home and they found me. And of course in classic fashion, just shuffled me off to bed, said, “Sleep it off.” And we never spoke of it again. So you would think finding your son sobbing uncontrollably, naked on the bathroom floor would be something you might want to talk about at breakfast the next day. “Hey! What say we do something different?” So we just pretended it didn’t happen. But for me, I’d gotten to the point I’d injured my body to the point I couldn’t work out anymore. I didn’t have the option of working out.

Paul: Because of the lack of food or the over-exercising or both?

Michael: Both. I firmly believe that it was a combination of both. And so because I just damaged the tendons in my hamstrings so badly I couldn’t run. My left leg, it was swollen so badly; to bend it was incredibly painful because it was prying the joint apart. It was a serious injury. So I didn’t have a choice.

Paul: What was the injury from?

Michael: I just tore the tendon somehow.

Paul: Oh, ok.

Michael: I mean, I remember what happened. I was running and I felt a pop and it started hurting and swelling up and that was that. So I couldn’t lift, I couldn’t run, I couldn’t do anything. My entire schedule, my order had been broken. And so now I had to do something different. And so …

Paul: Did you ever feel like that was the universe kind of throwing you a bone?

Michael: Or well a giant boulder, like, “Hey, dummy!”

Paul: Yeah.

Michael: “We’re trying to tell you something!” And, so, yeah, and it wasn’t much longer after that that I graduated from college finally and so I moved out. For some reason in my mind, “Ok, now you have a degree, you can live on your own.” And I moved out and that was the beginning of the change because now I wasn’t with them.

Paul: And had you started seeing a therapist? Because you had taken some psychology courses so you were beginning to …

Michael: No, I wish I had. It took many, many more years until I got really screwed over in the dot com bust before I began seeing a therapist. I was all for it for everyone else. Man, that’s a great idea. You know, therapists are awesome. You should go talk to somebody! Well, are you going to? Nah, nah, nah.

Paul: You had a shower to cry in.

Michael: Exactly. There are some jokes to be had here; I don’t want to mess up my humor. Yeah, it was, you know, such similar asymmetry that a lot of people have, right? You see everybody else a lot more clearly than you can see yourself. And so I had begun seeing a therapist. You know, I read a metric ton of self-help books, though. That’s gotta count for something. And I talked to everybody who’d listen about all these philosophical issues in general that were just dancing around the root problem because I didn’t even know what the root problem was. See; at that time I didn’t even realize that it was abuse.

Paul: Yeah, and that’s why therapy is so good cuz like reading the self-help book before you understand what happened to you, you know, it’s kind of like reading a road map before you know how to read.

Michael: Yeah. It’s just crazy. And so, I mean, I remember this concept of people looking at me talking about something I was really excited about, and I remember it’s like why aren’t you doing this, right? Buddy, you got things to work on. And I was just not there and that’s the part that’s frustrating. And, you know, so many people suffered. I mean, I didn’t abuse them physically, but I just think I was probably a real asshole, hard to be around at times. Not because I wanted to be, but because I just had all this stuff I didn’t know how to process.

Paul: Were you controlling with other people?

Michael: I don’t think so. I think I isolated myself, is the thing. But I know—like in work relationships and things I was probably incredibly touchy, very sensitive to everything. I think I’m a sensitive person in general but hypersensitive.

Paul: So criticism really hurt?

Michael: Oh yeah. You know, it just set me off.

Paul: Would you go to lengths to avoid criticism, sometimes even like manipulating situations or bending the truth? Or how would you try to control the potential to be criticized?

Michael: Yeah, my birth mother, who may be the laziest person on the planet, always told me I was lazy. Wasn’t good enough, didn’t work hard enough. So I learned to overachieve, right? There was no way somebody was gonna outwork me. You can do nine hours a day? I can do ten. Oh, you want to go eleven? I’ll bring twelve. Ha! I don’t need a Saturday. I mean, that’s my thinking. I wasn’t even that direct and conscious. But that was my—that was how I controlled it. I would outwork everyone. I’ll outrun you, I will out-whatever you. It doesn’t matter. I’m gonna outdo you in every way. So you don’t have any opportunity to say I did something wrong. There’s gonna be no doubt in my mind. I didn’t feel comfortable letting people have an honest judgment. So, you know, we laugh that—my therapist is brutally honest to me, right? I mean, it’s kind of almost a joke. There’s no dancing around anything. And—but that’s important for me to get that feedback. And to have a relationship with someone where I can take that feedback and not feel like, ok, this is a person who’s trying to control me with their criticism or trying to abuse me or make me feel a certain way where they can say, “No, this is what I see happens. This is what you’re doing. If you don’t like the result, let’s do it a different way.” And for years I couldn’t take any sort of feedback like that. I would implode if I got that.

Paul: Even from your therapist or just from everybody?

Michael: Oh no, before I went into therapy.

Paul: Ok.

Michael: But when I was younger.

Paul: You would implode; you would just be overcome with self-hatred? Or would you lash out?

Michael: No, I think because I was a victim of being—of that lashing out, I was never that kind of person, right? It was always myself. Self-abuse. That was the thing I would do.

Paul: And there seems to be—that seems to be with people that turn it inwards, then they, you know, restrict the food or they do other things to punish themselves and to push themselves and then that victory seems to be their way of cleaning the slate and saying, “I’m ok now. I’ve re-achieved my worthiness.”

Michael: Right. For me I think there is a certain amount of penance. So, you know, I would hit myself. I was never like a cutter, because, well, that leaves permanent—people can see that. But I would just physically beat myself even. Because I think in large part it was familiar. That was a punishment I knew.

Paul: What would you do?

Michael: Most of the time I would just punch myself in the head as hard as I could. And it would hurt. But sometimes I would bite my own arm, right? Just any pain I could cause that would help me feel, I think, again. I mean part of it was it brings you back into your body. But I think a lot of it for me was that I suck, so I have to suffer. And I’m used to that, so …

[MUSIC]

Paul: Ok, you know what that sound is. It’s time to give our sponsors some love. And our sponsor is Squarespace. You know, one of the great things about doing a podcast is you get what it is that you—who you are, deep inside, it’s your place on the Internet to let that shine. And Squarespace is such a great way for people that aren’t web savvy to be able to create a beautiful looking website for almost no money. I’m tempted to say it’s completely free but that probably wouldn’t be true. It’s about $8 a month and you get a free domain name with that if you sign up for a year. And you can get 10% off if you go to Squarespace.com and put in the offer code HAPPY. But they just—it’s drag and drop. It’s 24/7 support. You can connect all your social media to it. It’s just—it’s a really great, really great way that is not intimidating. Because I think that’s the biggest thing that keeps us from doing things is—it seems like overwhelming or complicated, or they’re gonna try to fuck you. Maybe that should be their slogan at Squarespace, “We’re not gonna fuck you.” Squarespace – everything you need to create an exceptional website. Or maybe that’s Squarespace – secure your place on the Internet before you lose your place on the planet. That might be a little dark. Thank you, Squarespace.

[MUSIC]

Have you ever sexualized that masochism or that pain? Has that ever become a thing? Because one of the things I see on surveys that people that turn their anger inward is oftentimes it’s expressed in their sexuality as well where they like to experience pain or degradation or humiliation.

Michael: Not at all, in fact, the opposite, right? I’ve never found that even remotely interesting. To me, the two are different. Pain is pain and sex is sex. And I understand intellectually that some people enjoy that but not at all for me. In fact, as far as you can possibly go. Part of it is, probably as a victim of childhood abuse, but I don’t like to be tied up or restricted or anything like that. And so the thought of letting somebody handcuff me and whip me would drive me crazy. I’d, you know, rip the headboard off the wall and run down the street before I would let that happen.

Paul: Yeah. I’m always fascinated how sometimes trauma becomes infused into a person’s sexuality so that’s one of the reasons I asked that.

Michael: Yeah, I kind of responded by taking that and putting it into my life in another sense. And so I, in essence, went through my own boot camp. I was gonna make that my experience, right? So I think it was a part of taking back the pain and the suffering and turning it around. So, ok, if I’m gonna be miserable, at least when I’m done being miserable, I’ll be able to take care of myself. So it’ll be different than it was before.

Paul: And I would imagine too it’s much—when you feel like, “I’m going to experience misery in this world, well, then I’m gonna do it to myself. Then at least I’m beating it—instead of waiting around for it to happen, I’m gonna be the one and I’ll have some control over how I suffer.”

Michael: Absolutely. And my startle reflex is just off the chart. So I don’t like any surprises like that at all. So, I mean, I think that makes a ton of sense from my perspective that, “Ok, I’ll know when it’s coming, right? Ok, it’s 4AM. I know it’s coming. And I’m doing it to myself. It’s my choice.” And there’s a lot of that aspect of control and I’m sure that’s part of the reason why I was harder to be around when I was younger because that sense of control—not necessarily controlling others but controlling my entire environment, which included other people.

Paul: I wonder how many people find that aspect of the military to be alluring because it’s kind of built in that sense of—at least, you know, the basic training and stuff like that? I’m thinking of one listener in particular that I am familiar with who’s in the military and does extreme endurance stuff, and that just always—sometimes my brain is just thinking about a hundred different things at once.

When you got into therapy, what are some seminal moments in your process of therapy that kind of—where light bulbs went off or you experienced an emotion that you had never experienced before?

Michael: Well one of the things that came out in therapy was that I suffer from PTSD. And my therapist is great about not putting labels on me. But I was reading this book called All the Fishes Come Home to Roost and she talks, the author talks a lot about how her experiences with PTSD happened. And the thing that to me it triggered was she talked about a PTSD blackout being different than when you black out when you’re drunk. That it’s like a jump cut in that one second you’re there and the next instant you’re somewhere else with absolutely no idea that any time has passed. And so I had two of those incidents when I was younger. And one of them was during my first week in high school, I was a freshman. And this other kid, for whatever reason, threw a soda on me. And jump cut. Next thing I knew I was twenty feet away and I had him up against the lockers and the teacher was pulling me off. So to this day I don’t know what I did to that kid. But whatever it was, nobody messed with me in high school ever again. And so at the time it’s incredibly frightening. What just happened? I don’t know what happened. But I didn’t know what it was. And so reading that book, it allowed me to kind of, oh, I think I know what’s going on here. I think I can kind of start to get a handle on what’s going on. But why would I do that? What trauma did I have? Right? Stupid question. Well, you kind of lost your dad when you were four and then were abused for a decade. Oh, ok. Now I’m starting to get that and starting to understand that. And so for me because I have this overachieving part, I want to always be perfect and to do the right thing and to do everything. But it’s not something that—healing myself does not lend itself to analysis. Or that kind of hard work in the sense of rote. Like if I get up and I do the same exact thing every day at 4AM, eventually I’ll be better. It requires a vulnerability that was really heard for me to get to. Because I learned, apparently, early on, right, if you’re vulnerable, you get hurt. So you need to toughen up. Don’t be a pussy. Just take it and get past it. You’re stronger than this. And I remember having physical issues and thinking instead of saying, “Gosh, I’m in pain. I need to take a couple weeks off, maybe take some Ibuprofen, put a little ice on something,” thinking, “Oh, come on. Just get past this, right? Just work through it.” And I would do that in a lot of different places. And so part of, for me, the ability that allowed me to start the process of healing was to realize that I can be vulnerable, that I can have emotions, I can have moments of weakness, that I can show that vulnerability to other people and not have them take advantage of it. And that was a process that took a very long time. I remember in one of the first sessions with my therapist, I don’t think it was intake, but it was pretty quick thereafter, I told him honestly, not trying to put on airs, “You’ll eventually betray me. I know this. And I’m here anyway.” Which is, when you say it, kind of a stupid thing. If you knew that was gonna happen, why would you show up, right? And I think there’s a part of me that was hoping that wouldn’t be the case but I think that’s how I thought, right? And so for me that ability to go and to be honest, and I know I wasn’t as brutally honest then as I am now, because I had to learn that skill, but to go and tell him something—I think of it like a game of cards, right? I have 52 cards of abuse and so I put one out and I see what’s his bid, right? And I put another one out. Like, how far can I go before he’s going to use this against me somehow? Which is, of course, a stupid thought, but it’s the way your brain works when you’re in the middle of it. And he never has, right? And so that allowed me to kind of—

Paul: How many years have you been going to see him?

Michael: It’s, I think, probably twelve now. But there was a break in the middle where I stopped going, I don’t know why.

Paul: He needed to take time out to betray you.

Michael: He was plotting my demise. Yeah, I don’t know what it was that really brought it about. But then what happened was two years ago when I found out about all of the abuse I knew I had to go back into therapy. There’s no way that I could—

Paul: Found out about all the abuse going on in the satellite family?

Michael: Yeah. In my family of origin that had gone on decades ago and is continuing, right? So it’s common, I guess, for some victims of abuse to seek that out again. So it’s not uncommon I guess in some cases for families to have that generation upon generation upon generation of abuse, right? It was actually a little bit in some sense worse for me. I was sent to a private religious high school that coincidentally two of the faculty are currently in prison for child molestation. And I suspect more of the faculty were. For a high school of 500 students, it’s a fairly high proportion of molesters in the populace. And I talked to my therapist about it and he said, “Well, a lot of times they recognize the environment that’s set up for them. That it’s an environment where they can predate as best as possible. And so in that sense again—but that is where I went from. You know, I went from ok, molesters at home to molesters at school, back to home. It was a crazy, crazy thing. But for some reason it was ok if it was just me. I mean, it’s heartbreaking to say that. If one of my kids said that, oh, well, yeah, I was abused but was just me, it’s ok, it would break my heart anyway. But I seem to think that way. And so when I found out, no, it’s not just me, it’s generation upon generation, I knew. I was at least far enough along where I knew this will crush me without help, right? And so that ability to say, “I can’t do it on my own.”

Paul: And what was it that came to light that let you know all of this stuff was going on?

Michael: Well …

Paul: Conversations you had with people where they let things slip? Or did you see something happen or what?

Michael: So, my niece had been going through a lot of trouble in her life, struggling at college, struggling at her job and different things, and there was always an aspect to her behavior that made me think there was a sexual component and I thought, “Well, maybe she’s just a lesbian. They’re a homophobic, racist group of people. If you happened to be a lesbian, that would be a bad place to be, right?” But then—

Paul: You were thinking that maybe she was getting picked on because she was gay and that’s …

Michael: Right, especially by her family.

Paul: I see.

Michael: Because they are so intolerant of everything, right? I mean, it doesn’t matter, you pick the wrong condiment for your hot dog and they’re all over you, right? It’s incredible, the pressure. But then she had to be hospitalized. Basically like a 5150. Medical professionals said she has to be put into the hospital and cannot leave. And they couldn’t cover it up. And suddenly that was out.

Paul: And this is your birth sister’s kid?

Michael: Yep. And so then we started kind of digging into that, and oh, she’s going into therapy and this is a group that does not believe in therapy, so I’m, “That’s kind of odd, why is that?” And one day she texted me and just kind of mentioned offhand, “Oh, yeah, by the way, did you know my father molested me for my childhood?” Huh, no I did not.

Paul: So there was something about you that was safe. She knew that you were in therapy. Were you the flakey, the fruity uncle who is into talking about his shit?

Michael: Yeah, Mr. Feelings. Yeah, that was me. I was the guy. I was the guy that was not religious, that was not homophobic, that was not everything else they were. I was the, yeah, the fruity guy who moved away to the land of hippies. And, so, yeah, I think there was a certain comfort level she had where she said she knew instinctively that she had to talk about this, and that I was relatively safe. And then immediately began backtracking and felt guilty and trying to minimize, right? And …

Paul: Just protect the abuser.

Michael: Yeah.

Paul: Yeah. That’s so common. It’s so common.

Michael: I’m like a dog with a bone, though. When I found out that she had been molested, it was on, right? I’m getting involved here, you know, I have an agreement now with my therapist that I cannot drive someplace and kick doors open without getting his agreement first. I have to check with them first; because I was ready to load up the car and we were gonna go take care of this, right? And I wouldn’t let it go. And I’d call up, “What’s going on?” I asked her mother, my sister, “What’s going on with this?” “Oh, well, you know…” “No! Not ‘well, you know.’ That’s gotta be hard. How do you feel about this?” “Well, what are you gonna do?” Again!

Paul: This is your child.

Michael: Yeah. And so I started, like I said, digging. I was just on it. I was so into it.

Paul: And now was your niece at this point backing away because she’s like, “He’s making fucking waves and this is gonna get ugly?”

Michael: Yes. Oh, yeah, she was immediately, “Please stop. Please don’t do this, right?” And I said, “I can’t.”

Paul: So she wanted somebody to know, but not to do anything about it.

Michael: Yeah, I think that’s it. I think there is the competing forces inside of her. And I tried very hard to say, “Look, this is not on you, right? This happened to you, you need to get help. You need to get out of this environment, you need to…”

Paul: How old was she?

Michael: Well, while it was going on I want to say maybe seven to fourteen or what have you. So—but at this time she’s much older. But the damage had been done, right?

Paul: So she was an adult then at this point?

Michael: Chronologically yes but very stunted, which I think is not uncommon with victims of sexual abuse as a child, right? And so she should have been able to take care of this on her own in some sense, except she’d been so damaged.

Paul: Now were there siblings of hers still in the house that were minors?

Michael: Yep. And so I talked to my therapist about it and I said, “I really feel like I need to call Children’s Services.” But at the time I hadn’t broken off contact, and I said, “They’ll hate me forever.” And he says, “No problem because I have to call now. I’m bound by my oath.”

Paul: That’s awesome.

Michael: And so Child Services was contacted because of that and as far as I know nothing happened from that. How that could be, I don’t know.

Paul: I did an interview, I haven’t aired it yet, but I did an interview with a guy that works for Child Services and there has to be proof. They can’t take somebody away just based on evidence—the proof can be a child saying this is happening to me and they will take the parent out of there, but if the child isn’t the one saying it they need, you know, I hate to be graphic, but they need a semen sample on underwear or, you know, something like that. So it’s—their hands are tied a little bit if there isn’t a certain amount of cooperation or physical evidence.

Michael: Right, I don’t know if there’s any physical evidence. She told her therapist and psychiatrist. I would presume that’s where all of this came out. But, so, I remember vividly, speaking of physical evidence, talking with my birth mother about this. And she actually said the phrase, “Well, at least there was no penetration.”

Paul: Oh, my God.

Michael: And I couldn’t believe it. My jaw dropped. And for a while I was furious. And then my wife brought up that that is not the reaction of a healthy person. That she probably came from a situation where there was penetration.

Paul: Yeah, or there wasn’t and that’s what she told herself and, you know, either way, that qualification, which is so common with people that are abused, is to find some part of it that is ok.

Michael: Right, so I figure that’s gotta go on our headstone. But, so I’m working through this. I’m saying, “I have to do this.” And it comes to the point where I realize on a phone conversation with my birth mother, “I just can’t do this anymore at all.” In the middle of a conversation with her, I say to her, “I can’t do this anymore.” And she says, “What do you mean? Can’t do what?” And I said, “All of this.” And I knew in that moment that was the last time I’d ever talk to her. Because here I’m dealing with this person that refuses to stand up for their granddaughter, to stop something that happened to them, and probably happened to their daughter. And still won’t stand up. I said, “This is so unhealthy. I have tried for my entire life to overachieve, to work hard enough, to make this family work and I’m done.” And you know, I am so much more free since I have said that. I thought about this on the way to work recently. I realized I hadn’t talked or thought about these people, affectionately known as the shitheads, for months. And I was so much happier. And that sounds horrible because in some sense I don’t have a family. I’m kind of orphaned. But just to have that energy out of my life is an amazing thing.

Paul: Do you talk to your niece ever or is she just withdrawn?

Michael: We occasionally trade text or email. She’s still very much into her problems and she’s not able to have a conversation so I have to keep a pretty firm arm’s length. I wish I knew more. I wish she was getting better help, but I don’t know. My therapist tells me to have faith in therapy, that eventually she’ll be able to get where she’s healthier, but it’s a long journey and she’s just starting.

Paul: And the fact that she was able to text you is a good sign. You know, I try to get into the heads of these people like your mom that just want to brush it under the carpet because they don’t want to look at what happened to you. And I would imagine in their mind it’s like, “Well, if we’re gonna start talking about that, you know, it would almost be like saying, ‘Well, if I’m gonna help you with your taxes, I have to do my taxes, which I haven’t done for the last thirty years.’” You know, it’s gotta feel like that overwhelming and just undoable. It must just seem undoable to them. And not necessarily a moral choice, just a, “I can’t. I don’t have it in me to face that.”

Michael: And so one of the plus sides I suppose to my compulsion to overachieve is I can’t give up. And so I know that feeling well. I mean, I went through decades of, “This is impossible.” Honestly I don’t say this to be excessive or to get to people’s feelings, but I never thought I would live to see 25. I just couldn’t imagine how a person could live this way for year upon year upon year. And so I can understand when you’re in that kind of feeling why a person would try to kill themselves. But I couldn’t because it was quitting. Right? So I had to stick it out and luckily I eventually got to a point where I could start healing myself, start making progress. But, yeah, I get that. I get that idea of it’s just—it’s impossible. I didn’t have the tools. I was not given the tools to deal—to cope with this. And when you think about it, what four-year-old has the tools to deal with the death of a father in the first place? Let alone, hey, three months later let’s bring this abuser in because life isn’t bad enough yet for these kids; let’s make it really bad.

Paul: So what are some of the tools that you draw upon that you’ve learned in therapy? Has there been another learning thing other than therapy and self-help books? Are those the two main things?

Michael: Well, you know, the interesting thing is I’ve actually been able to move physical exercise back into my coping mechanism as a way—I almost consider it meditation. Not in the sense where I’m counting my breaths.

Paul: It has some moderation to it. It’s not obsessive.

Michael: Yeah. Well, it depends, if you ask my wife it still might be a tiny bit obsessive.

Paul: She’s—Christy is sitting on the bed in my hotel room nodding her head and laughing.

Michael: But that’s one of my coping mechanisms. Another thing, I think, is I’ve learned to find balance and that’s been probably one of the hardest things I’ve done, is for me, and maybe a lot of people, extremes is a lot easier. It’s easier for me to say all or nothing. And that thing about, well, I can skip today, or I don’t have to go into work today even if there’s something big going on, or what have you. That ability to say, “I can balance my needs with others’.” Instead of when I was growing up, it was my needs zero, nothing, everyone else’s needs, all.

Paul: Because there’s a beautiful oblivion in getting lost in other people’s needs. There is a certain narcotic quality to it.

Michael: And so that part requires constant vigilance to make sure that I’m still readjusting. And so, you know, a while ago, well maybe six or seven years ago, I talked to my therapist, I said, “Maybe pharmaceuticals is the way to go here.” Thinking this has got to be easier than this. And he laughed at me. All right, so back to work. But I would love to have things like that. But I do try to mix in different things that respond for me. Going for a walk with the dog. Simple things that help connect me.

Paul: By the way, I’m a believer in pharmaceuticals if they’re necessary.

Michael: Oh yeah.

Paul: Not as a solution to everything. You know, I think talk therapy is a great place to start and oftentimes then the therapist can help you kind of assess whether or not you need to go see a shrink for …

Michael: Well I think it would be fantastic if I needed that I could get it.

Paul: Do you feel like you’re able to get to place where you’re functioning and you’re achieving enough joy and peace in your life that you can do it without meds?

Michael: I think he was right. I think it was the instinct of “this is too hard, this is too scary.” I want to look for a shortcut, a way out. Which is why he laughed at me and told me to get back to work. But that’s something where I don’t have that luckily that problem where I need some sort of intervention in that sense. But I look at it from the standpoint of, you know, balance in everything. Eat some cake now and again guys. Bacon won’t kill ya every now and again, these kinds of things. But by the same token, try not to have a bacon double cheeseburger every day for lunch. Because that obsessive part is always in there. Well gosh; if it made me feel better yesterday, I just need to keep doing that. I need to keep doing that. I need to keep doing that. And so I don’t have the obsessive thing like counting stairs or doors or all these kinds of things but boy, I mean, it’s so much easier, that all or nothing to get into a behavior instead of having to balance things. And so for me that thought of balance and disconnecting myself from a lot of the negative energy that I encounter, not just my family of origin, but I’ve forsworn watching the news because it never makes me happier, right? It’s always panic and pain and heartache and I don’t need any more of that. I have a full dose already. This lifetime I’m all filled up, don’t need anymore. And so—

Paul: I’m glad you said that. That makes me feel better because I also had to really, really pull back from that because it was just really bumming me out. And for a guy that hosts this podcast …

Michael: That takes quite a bit.

Paul: But go ahead.

Michael: So those are the kinds of things that I think work for me. I happen to live in an area with a lot trees around me. I love trees. They’re soothing to me. I love the sound of rain on the window, right? Things like this help me to maintain this. But I think probably the single greatest thing for me is that ability of just getting a perspective to realize that the feeling I’m having is a feeling and it’s not necessarily a reality. And so for so many years I chased that, right? I’m feeling this way and that’s the way things are. That person’s out to get me. Or everything’s gonna be screwed up, I’m gonna get killed and everything was all that sense. And to be able to just maybe through experience, maybe it was just enough years on the planet, you start to say, “Wow, I’ve felt this way before. And guess what? It’s gonna pass. It’s gonna suck for the next two days, but I’ll be ok.”

Paul: And I think therapy is such a great way to have that difference pointed out to you. That what you’re feeling isn’t necessarily reality. You know, the therapist might not be able to say, “That isn’t reality.” But they can help you put the question in your mind of, “Is what I’m experiencing actually what’s happening?” So you begin to go, “Maybe it’s just a negative voice that was planted in my head when I early that’s kind of out to get me.” And that can be incredibly freeing. And a book that I’ve recommended many times and I’ll recommend it again, that is so good at identifying that negative voice is a book by Eckhart Tolle and it’s called A New Earth and you can get at Amazon, and of course I ask you to buy it through the search portal which we have on our website. But, yeah, those are—distinguishing between our feelings and reality is huge. It’s huge.

There was something else that I wanted to ask you. I can’t remember what it was. Was there anything else you wanted to add before we do a—fears and loves?

Michael: Well I think I’ve gone through the top of them.

Paul: I just want to ask Christy, your wife, if you can scoot down here a little bit. I’m gonna hand you the mic or maybe you can hand her your mic. What is, if you can—what’s the difference you’ve seen in Mike? You guys have been together twenty years. Is there kind of an arc of his change that you experience and how you as living with someone who’s been through so much, what has been helpful for you and what you’ve learned?

Christy: I think, I mean he touched on it earlier, the obsessiveness with the exercise. He would get sick. And I would just cavalierly, not knowing kind of the background and why, say, “Just take a day off. It’s no big deal, you’re not gonna die, you know?” And he was just—he would get so angry. And it actually—it wasn’t until he brought it up now, the hitting, I remember that and it used to scare me because I come from a history of abuse too. And I realized, that’s right, he doesn’t do that anymore. So I definitely see that. One thing—and because I was a child of abuse, when things get tense or something that would have set him off, I think I get—you know, I tense, “Oh, here it comes.” I tense up and then it’s like, “Oh, he’s doing ok. He’s figuring it out. We’re all right.” So I definitely see that that hair trigger is gone. It’s smoothed a bit. And we both, with lots of therapy—we share the same therapist, he’s—like he said, we’d move him in if we could.

Paul: That’s so beautiful; he sounds like such a great guy.

Christy: Oh my gosh, I feel like he saved my life. Cuz I dealt with depression I’m sure after our second son was born. And then just all the abuse in the past. He’s definitely saved my life. I related to your interview with Teresa and that moment where you are contemplating, you know, you’re making a plan.

Paul: So you had some serious PPD. Post partum.

Christy: It wasn’t—it’s weird, it wasn’t post—I don’t think it was post partum. I think it was just depression that never was addressed. And then now you’re a mother at home alone with two small children with no outlet. So I don’t think it was hormonal, triggered by the pregnancy, it was just undiagnosed depression.

Paul: I’ve also heard people say that just seeing the innocence of their children sometimes they get a perspective that, oh my God, I was that. How could somebody abuse or mistreat such a beautiful, innocent little person.

Christy: Oh yeah, exactly. Exactly. And I think seeing the potential, you know, something then triggers you and you get frustrated and you’re thinking, “Oh my God, that thing that I never liked, I don’t want to become this. I don’t want them to have to become who I am. I don’t want them to fear me. I don’t want them to cower.” I don’t want, you know, when you see that you can get so angry it scares you. And, yeah, that innocence. You don’t want to abuse them.

Paul: But don’t you sometimes think that if you both hadn’t gotten help, you would have made a pretty sweet episode of Cops?

Christy: Oh yeah. I guess there’s that.

Paul: Well thank you for sharing that and it’s really sweet seeing you here supporting him and seeing the fondness and the love and vulnerability that you guys have. It’s like, you know, marriage—so many people shit on marriage and it’s really what you put into it and how committed you are to making it work. And it’s a lot of fucking work and there’s many times that both people are like, “What the fuck?” But when I get to see something like I see between you guys and just how you interact with each other, it’s the opposite of the news to me. It’s the opposite of the news. It’s like—I’m just reminded of how beautiful and resilient the human spirit is and the power of love. The power of people to be there for each other and to embrace each other’s imperfections and clumsy struggle towards the light.

Christy: I think—

Paul: She just asked for the microphone and I thought it would have been so awesome if he hit her. It would’ve just …

Christy: I think that that’s the thing that’s great. You know it’s corny, but we have these opportunities with our own children when something will happen and we get to rewrite the script and do it the way we wish somebody had done it with us and in the end, we, all four of us will usually end up laughing, you know. It’ll be something—somebody came home with a bad grade and normally it would have been the end of the world for him and I when we were kids, and, you know, we still correct the problem, we still redirect them and we still tell them what our expectations are but in a way that is loving and kind and we can all walk away laughing.

Paul: And isn’t zero or one hundred.

Christy: Yeah. Yeah, and so it’s just so great to be able to go, “See, you can do it this way. You didn’t have to do it the way you guys did it. We can, you know, break that cycle.” Which is really important to both of us.

Paul: Nothing makes me happier than seeing that. Truly, nothing makes me happier. That’s so beautiful.

Let’s do some fears!

Michael: All right.

Paul: I’m gonna be continuing a list of fears and loves from a listener named Kate. She says, “I’m afraid that I’m crazy.”

Michael: I’m afraid of dying in a car wreck like my dad.

Paul: Boy, fucking deep right out of the gate. Christ, right to the Mariana’s Trench! “I’m afraid that I will feel this way forever.”

Michael: I’m afraid that I’ll become abusive monster like the one who terrorized me.

Paul: “I’m afraid that my eating disorder made me infertile.”

Michael: I’m afraid of being unable to defend myself, either through age or infirmity and becoming the victim of abuse again.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I’ll always be bulimic.”

Michael: I’m afraid that at this very moment this cancer that will eventually kill me is stockpiling resources and finalizing its plans for my demise.

Paul: “I’m afraid that my teeth will fall out.” I have that one too by the way.

Michael: I’m afraid that I really am a whiny pussy and this podcast will be the confirmation that the rest of the world needs to justify ignoring me.

Paul: I have that feeling every week when I put it up. I’m like, “Oh, man.” And it’s that negative voice in our head, there’s nothing it won’t attach itself to. That’s why that Eckhart Tolle book is so good because it points out how the negativity and the ego are just barnacles that will attach themselves to anything.

Kate says, “I’m afraid that my roommate and I won’t be able to renew our awesome lease because of some stupid mistake of mine.”

Michael: I’m afraid that I’m as bad of a parent as my birth mother was and that I’m perpetuating the cycle of dysfunction for another generation.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I won’t wake up in the morning because purging caused an electrolyte imbalance.”

Michael: I’m afraid that I will never be good enough for the ones I love and that they’ll suffer or die because of my inadequacy.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I will get fingerprinted for a job and I’ll be connected to some crime that I don’t remember committing.” That is awesome.

Michael: I’m afraid that someone will leave the toaster oven on when we leave and the house will burn down while we’re gone.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I will always feel like I’m the worst one at my job.”

Michael: I’m afraid that someone will pull the episodes of Love Connection I was on and use them to publicly shame me.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I won’t get into grad school and I’ll get stuck at a job that I hate.”

Michael: I’m afraid that my therapist will quit the practice, run off to Thailand or die before I’m healthy enough to make it on my own.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I’ll have to ask my parents for money.”

Michael: I’m afraid that I’ll never be healthy enough to make it on my own.

Paul: “I’m afraid that my parents think of me as an emotional burden.”

Michael: I’m afraid that I’m not really that funny and that people’s laughter is the kind you reserve for the awkward dork at the grocery store who you want to just go away and leave you alone, but you know that you won’t until you laugh at his stupid joke.

Paul: I love the synchronicity in these things. We always get them. Here’s the next one on her list: “I’m afraid that I’ll never get the hang of things like grocery shopping.” I’m telling you, it’s crazy.

Michael: Awesome. I’m afraid that I’ll never get a good night’s sleep again and die from fatigue or sleep deprivation.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I’ll never find a slipcover for chair that I hate.”

Michael: I’m afraid that this is all a giant conspiracy designed to drive me crazy and that it has already succeeded.

Paul: “I’m afraid that I need knee surgery again.”

Michael: Ok, so I’m out of my prepared ones. And I think the unprepared wouldn’t be very good.

Paul: Let’s go to loves then. I’ll start with Kate’s. “I love when I get over a cold faster than I think I will.”

Michael: I love the smell of my grandmother’s house because that smell means love.

Paul: “I love when I order a vodka soda and I don’t have to ask the bartender for the lime.”

Michael: I love the word pantalones.

Paul: It is a good word. “I love beard burn on my skin after sex.”

Michael: It’s hard to top that, boy.

Paul: That is a good one. That’s very picture painting.

Michael: And this is not synchronicity I don’t think. I love the feeling of freshly clipped fingernails.

Paul: Close. “I love the first kiss when you wake up with someone in the morning.”

Michael: I love a really good carne asada burrito made by a food truck.

Paul: “I love talking to old friends on the phone for hours and feeling the same connection as I did when I saw them every day.”

Michael: I love the moment something really hilarious happens and you look around to see if anyone else noticed and only one person did who’s a complete stranger and you share a momentary connection and chuckle.

Paul: That’s a beautiful one. I love that one. “I love when I’m the first person to use a new tub of margarine and getting to see the swirl on top.” That’s a great one.

Michael: I love when I make someone laugh so hard they do a spit take, can’t breathe, or pee themselves.

Paul: “I love oatmeal cookie dough with tons of cinnamon in it.”

Michael: I love that fact that while I didn’t think I would live to see the 21st century, it’s actually a lot better for me than the 20th century was.

Paul: “I love when I reveal something about myself and it is totally not as big a deal as I thought it would be.”

Michael: I love when a photograph that I thought would be really took it turns out in fact to be really good.

Paul: “I love lavender spray on freshly washed sheets.”

Michael: I love when I craft a really funny tweet that merits a response from my cousin.

Paul: “I love Oreo ice cream especially when I get a bite that has almost a whole cookie in it.” Yeah that’s a great one.

Michael: I love driving at night during Christmas time with all the Christmas lights reflecting off the rain-slicked pavement while listening to Christmas music.

Paul: That’s a beautiful one. “I love feeling like I am friends with my older relatives.”

Michael: I love one of those sessions with my therapist where I come away with an insight that rocks the foundations of my reality, like one of those sideways earthquakes.

Paul: “I love the feeling of the inside of a brand new sweatshirt.”

Michael: I love warm puppy smell. The smell of my 85 pound Rhodesian ridgeback when he’s all roasty toasty under the covers.

Paul: “I love puppy breath and little pin puppy teeth.” Even if it hurts when they’re teething and they’re biting your fingers. Yeah, I could drink a drink that smelled like puppy breath. That’s disgusting. “I love helping my dad put up their Christmas lights.” Are you out of loves?

Michael: I’m out of loves.

Paul: Ok, then I’m gonna end on her last one. “I love when I’m able to remember that perfection is unattainable.” Wow what a great one. And what a perfect one to end on for this episode.