Episode notes:

No show notes for this episode.

Episode Transcript:

Episode 125 -- Randy Olea

Paul: Welcome to episode 125 with my guest, Randy Olea. I'm Paul Gilmartin, this is The Mental Illness Happy Hour, an hour or two of honesty about all the battles in our heads, from medically-diagnosed conditions and past traumas to everyday compulsive negative thinking. This show is not meant to be a substitute for professional mental counseling, it's not a doctor's office, it's more like a waiting room that doesn't suck. The website for this show is mentalpod.com, please go check it out, there's all kinds of stuff you can do there. You can join the forum, you can support the show financially, you can take one of the many surveys that thousands of people have filled out and are an important part of this show. That blows my mind sometimes when I think about that like 15,000 people have taken the surveys on the website. It's so cool getting to know...and when people take them anonymously there's something about what they share...I'm learning so much is what I'm trying to say with all these awkward silences. To give you a med update, I've been on 200mg of Lamictal, it's been added to my cocktail of other meds and I'm actually feeling pretty good. Despite those last 20 seconds I feel like I'm having an easier time forming sentences and putting my thoughts together. There was a period about six months ago where it was just so hard to put sentences together and it's nice to feel like that's maybe behind me, at least for now. That's the thing about being on meds, you never know how long the good is gonna last so you just try to enjoy it. So I'm in a good place and thank you guys for all of your support. Although I gotta tell you there was a little bit of hypo-mania, I think that's what it's called, in the first two weeks at that 200mg dose, and then like a switch flipping off it switched off, but it was a little scary there for a while, 'cause I was surfing the internet and looking at porn, and doing it really compulsively. Then like I said, just like a switch it flipped off, so it's nice to be back among the living.

I wanna kick things off with an email that I got from a listener who calls himself Johnny. And he writes "Hey there Paul. I just discovered the podcast via a review of Maria Bamford's new CD on The Onion AV Club. I'm not really pro or con on podcasts, it's just not something I've ever been into much. With every other social media platform out there I've already got some serious information overload going, you know. But I'm bi-polar 2, electric boogaloo, and I love Maria Bamford so I figured what the hell. That was Saturday, this is Wednesday, and I've already listened to 6 episodes. I'm on meds and my current cocktail has been working for several years now for which I am grateful. I've been in talk therapy with my amazing shrink for about a decade. My friends and family know I'm bi-polar and I even try to talk about it a little on Facebook, just to let people know that I'm dealing with it and to try and dispel some of the stigma and prove that I'm not ashamed of it. But your podcast, Jesus Christ. I'm hearing people talk about things I've never heard anyone say out loud before. Dammit, I'm tearing up. I've avoided contact with other bi-polar folk because I didn't want to have to deal with anyone else's problems. I'm a profoundly self-centered person and when I'm trying to deal with my own mental illness I can't give someone else the attention deserve if they start to talk about their own experiences, and in that way I think I've unintentionally isolated myself from any kind of help I could get from a larger community. So hearing other people, people whose work I know and respect, I started with the names I recognized, talk about the same things I've experienced has been, well, it's been a lot of things, but mostly I think it's relief. Relief that I'm not alone, and thank you for repeating that every episode. It's one thing to read or hear about other people's struggles through a third party but it's quite another to actually listen to someone talk about it in depth and in a way that's not really irritating or choking on its own sense of self-importance. You know, honestly there are a million things I want to say to you but there was one episode where you talked about seeking compassion and I realized that that's something I've been doing my entire life and I've made some really shitty choices because of it. That's just one example and I could go on, and I kind of want to tell you my whole life story but it's late and I'm still processing a lot of what I've heard and maybe you don't want to know about the gay BDSM scene in Chicago. It plays a major role. Lastly, I'm going to attempt my first support group this weekend. A former therapist recommended it years and years ago, but he called it group therapy which just sounded sad. But you talked about how much support groups have helped you so I decided to look one up where I live and see what I could find. There is one that is literally across the street from my apartment. I don't think it's any kind of a sign, just a remarkable and excuse-annihilating coincidence, so I'm going this Saturday. Why not, right? Keep up the great work, Johnny." Thank you so much for that, Johnny. That really touched me. And I'd suggest to anybody who's seeking a support group, even if the first couple of ones you go to don't stir anything in you or don't make you want to come back, try a half dozen different ones. Because I'll be honest, there's some shitty support groups out there, or the support network may be great but that particular support group in that location might not be the best one, so don't give up on them.

And I want to just read this happy moment from a listener named Sally. She writes "I remember actually taking time to lay in the thick carpet-like grass under a tree when I was around eight or nine. It was summertime and I was visiting my grandparents' farm. I was free to relax and be a child at the farm. I remember feeling the warmth of the ground radiating up into my body, the contrast of the cool shade over my face and torso, and the sun's rays still on my legs, the sound of the giant tree's leaves slowly being blown to and fro by a cool summer breeze. I remember thinking 'This is heaven.'"

[Intro/theme music]

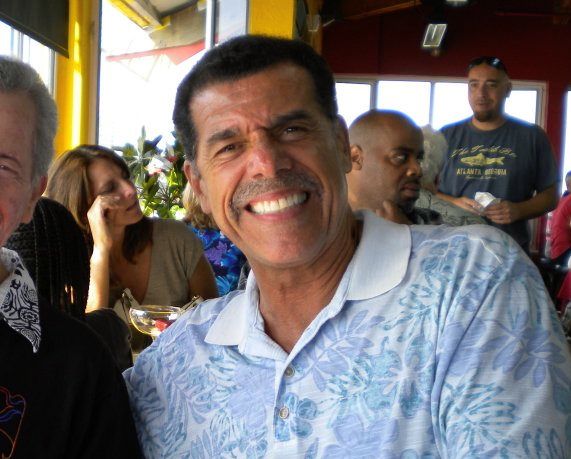

I'm here with Randy Olea who has been a friend of mine for probably eight years. We met through a support group and you were one of the first guys I met in a support group where I remember thinking 'That guy seems like a man, to me. That guy has the confidence that I wanna have, and the compassion that I wanna have.' I was dead wrong, but the point is you are somebody that I'm so happy to be friends with. And I've wanted to get you on the podcast for a while because I think my listeners would like to hear your story and get to know you. So you're how old?

Randy: I'm 62, I'll be 63 in September.

Paul: But you're a young 62, you still play basketball...

Randy: Playing full-court ball, Saturday and Sunday, go to LA Fitness two or three times a week, trying to stave off Father Time.

Paul: You're married, you have a six-year-old daughter.

Randy: And a 20-year-old stepson.

Paul: You're a Vietnam vet, you've been sober for 25 years?

Randy: Yes, 25+.

Paul: And you grew up in Los Angeles?

Randy: I was born in East LA, just like the song, and raised in Pico Rivera until I was 12 or 13, and then we moved to Temple City. I don't know if you know those areas?

Paul: Uh uh.

Randy: OK, a lot of gang activity back then. Of course gang activity was brass knuckles and switchblades, and being in a gang today is not quite...I mean, we used to meet at the park when you wanted to have it out back in those days.

Paul: You're Mexican-American?

Randy: Mexican-American.

Paul: Second generation?

Randy: Second generation. My dad was born in Texas, my mother was born in LA. Funnily enough, speaking of my dad, he dropped out of our lives years and years ago and came back in when my mother passed away in '85, I think guilt brought him back into the picture and then he disappeared after about a year of trying to hang out with us. He had never met any of his grandchildren, and I was watching an episode of Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel, and they were profiling this young white kid who has brought all these old Negro League players back together again because he's been researching them and putting them back together. So I thought you know--

Paul: Not to play just to--

Randy: No, no, they're very old, many of them are dead. 'Cause that was back in the '20s-'30s-'40s.

Paul: So these guys are in their 90s.

Randy: Right. And 80s. This was before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in '47. In any case, I thought I'm gonna look up the East LA baseball teams, maybe even find out where my old man is 'cause we really haven't heard from him in about 20+ years. Found out that he passed away. I went on this site where you can put in your last name and it'll give you all the Oleas, for example, in my case, who've died in California. And found his birth date and he was living in Fontana, apparently, and he died in 2009. So he's been dead for four years.

Paul: What did you think or feel when you read that?

Randy: One of the first things that came to my mind, Paul, was I do not wanna die like that. I want my loved ones around me. This is probably one of the greatest revelations a man like me, who's had the kind of like that I've had...He was a role model, he was not a positive role model, but he was a mean son of a gun. He was mean, and he pushed us away and always kept us at arm's...The only emotion he felt comfortable showing was anger.

Paul: How would he express that?

Randy: Physically, usually. He broke my sister's nose a couple of times, broke a couple of bones. He would never last in today's environment in terms of child abuse. He was a classic child abuser, but he provided for us, we had three hots and a cot, so I can't blame him for not raising us, 'cause he did do that, but one of the key ingredients that was missing from our lives, my sisters and myself, was that emotional upbringing where love is expressed. You just met my daughter again, you got to see her after so many years, she's gonna be seven years old and there isn't a day goes by that I don't kiss her and tell her I love her. There isn't a day that goes by that I don't kiss my wife, tell her I love her. Or my son. His legacy is kind of a reversal of fortune kind of legacy. I do not want my family to ever doubt that I love them, and I don't want to die alone and I don't want them to be alone. That is an incredible revelation for a guy like me to have, to realize after denying myself so many years that comfort. I've had plenty of sexual experience with women, but not a lot of love. Not a lot of that kind of emotional attachment. And since I've been married, and a few years before that since I've tried to change my life to become more of a spiritual person and less of a physical person, if you will. It's changed. So I kind of felt badly for him for a few moments because we were there for him. We wanted him back in our lives. He just couldn't do it. He could not do it. And when you're thinking about your life and you're looking at your father, because I looked at my father and thought 'What made him that way?' And then I remembered all those summers that I spent with my Grandma Rose. She was mean. Every other summer we would spend one summer with our Grandma Mary, one summer with our Grandma Rose. When it was Grandma Mary it was parades, it was bouquets, it was great. It was my mother's mother. When we were gonna go to my Grandma Rose's, tears and fears. What is so ironic, this comes years after going through, looking at her life, one of the incredible ironic indications about the kind of person she was, in her backyard she had tiers and tiers of cactus. That's what she raised. We used to drive to the desert, we used to drive to Indio when I was a child, I remember this. Before there was a 10 Freeway that took you out there, we would drive for hours so she could go cactus shopping. What a revelation that was for me later on in my adulthood.

Paul: Give me some snapshots from you being around her.

Randy: Fear.

Paul: How would she express what it was that made you afraid?

Randy: She didn't want us talking too loud, we couldn't play too loud, we couldn't disrupt her, whatever she was doing. And I've got to tell you, you know those pictures you see of kids sitting in a corner with their face to the wall in a high chair? That was me, she literally made me do that. She literally faced me to the wall looking at the corner where the two walls came together. And my sisters, very early on, God bless them, I love them, and I have forgiven them for this, but they would collude and they would lie to my grandmother and say "Randy hit us, Grandma," and smack! In the corner.

Paul: And would she hit you too?

Randy: Oh yeah. She was a slapper. She was a hitter. So I realized that my father was brought up in this environment.

Paul: And what was her husband like?

Randy: Here's the thing. The only grandfather I knew was my step-grandfather, my Grandpa Pete. But he was her second husband, which I didn't know until years later. But my Uncle Chris, his half-brother, was the only uncle I knew from that side of the family, but he was Pete’s son. My father’s father was a professional boxer in Mexico, and I only met him once and he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Spanish. He looked very much like my father, he was big and he was imposing, so I really never knew him.

Paul: Did your father know him?

Randy: I suppose he knew him. We never had the kind of relationship where we ever talked about my father’s life. I never talked to my father about his past. Too much fear.

Paul: So what was your mother like?

Randy: She was an angel.

Paul: That often seems to be the case with the spouse of the abuser.

Randy: Yeah. She was a classic victim, you know what I’m saying? Everyone loved her, Aunt Lupita and Lupe, and she was loved by all of my cousins and of course us. But she allowed the abuse to occur. She did fight back and she paid for that.

Paul: What a terrible position...Especially when it’s that era of divorce is off the table. I imagine you were raised Catholic?

Randy: Right.

Paul: So divorce, you might as well tell God to go fuck himself.

Randy: Yeah. Now there was a moment in time where he left and it was heaven. We could breathe. Unfortunately for us he came back into our lives, and I remember those hollow promises he made: “I’ll never yell at you, I’ll never hit you again, blah blah blah.”

Paul: Was he a drinker?

Randy: He was not an alcoholic. He was mean, he was not an alcoholic. And he wasn’t’ the kind of guy that was only physical with us. I’ve seen him get into fights with men when he would play ball. He was…

Paul: Baseball? Basketball?

Randy: Baseball. Like I said, he played semi-pro ball. There was a Mexican league in East LA, played at Belvedere Park and all these other parks in East LA. So it was all Hazard Park, Belvedere Park, there were a lot of parks over there—

Paul: Very competitive, I would imagine.

Randy: It was competitive, as am I. That’s one of the things I got from him, that’s why I’m still playing ball. I love that kind of physicality.

Paul: There’s a muscle that we have in us that can only be exercised through butting heads with somebody.

Randy: For certain guys. There are guys, I’m sure you know them too, they have no response. They don’t care, they don’t wanna do it, or they’ll just go to the gym and lift weights. Me, I played yesterday and I got into it with a guy, we didn’t get to a point of…Just competing. The guy was guarding me and I was guarding him, and you’re bumping.

Paul: There’s something, too, about the oblivion of that focus, when it’s like ‘That motherfucker’s not getting around me. I will die before I let that person score.’ It’s not necessarily healthy—

Randy: And oh, the joy of scoring the last basket of the day. In your face. And that’s happened so many times. I’m a good ball player, so it’s fun. And I’ve had an incredible amount of injuries since I turned 50. In fact, everything happened after I got married. All my major injuries all happened since I’ve been married. How does that happen?

Paul: Did your dad show you affection when you were good at sports?

Randy: Let me illustrate a basketball event in high school. I was captain of the basketball team in high school, and my father really until my senior year never really came to see anything I did. He came to see some varsity football games finally. I had had a great game, and scored 24 points, a number of rebounds, just was kicking butt. So I come home and I go ‘Hey Dad, I made 24 points today in the game.’ And he said “You scored 24 points.” And that was all he said. My mother told me after I came back from Vietnam that my father was extremely jealous of me, athletics-wise. He was a good ball player, but he only excelled in baseball. I lettered in track, baseball, football, basketball through high school. I was captain of a couple of teams and I always excelled. And he apparently, according to my mother, hated that. And my father challenged me to push-up contests when I came back from Vietnam. He was an older guy at that point but he just couldn’t…And especially if he started to drink it would get very ugly sometimes.

Paul: But he wasn’t an alcoholic.

Randy: He was maybe a binger. But really that is not my experience of him, that he was drunk all the time. But when my mother died he guilt drank. And then things would come out.

Paul: It would have been so nice, when we were kids, if somebody could have just taken us aside and put their arms around us and said “You should know that even though they’re in adult bodies, you’re being raised by children. You’re being raised by a child, and understand that all this stuff that makes you feel terrible is not because you’re unworthy.

Randy: Well, it made me feel terrible. I have a perspective on it today, which is good, through my recovery. If I wanted to have any kind of peace, I had to go through and look at every segment of guilt and shame and self-loathing, and figure out why I felt this way. Why it was like this for me. Why I had these fears.

Paul: Were you a violent kid, or did sports take care of it?

Randy: Sports pretty much took care of it.

Paul: So when sports went away for the most part...When did you start using your fists?

Randy: Early, and then a lot when I came back from overseas. I was a bouncer in a Hell's Angels bar, you probably heard me say that, in Sacramento.

Paul: Was that before or after Vietnam?

Randy: After Vietnam. No, after, after. Everything was after. Before Vietnam--

Paul: Did you go to Vietnam right out of high school?

Randy: No, about six or eight months. I graduated in June of '68, so a year I was in training to go to Vietnam. I would have been there in August of '69 but then Hurricane Camille hit and we were delayed from that, and then my mother had some kind of physical problem, that delayed me, so I ended up going to Vietnam in November of '69. My birthday is end of September, so I actually turned 19 when I went there, so it was a little bit more than a year after.

Paul: What was your motivation in going to Vietnam? Or did you not want to go?

Randy: My best friend at the time, who's a friend of mine on Facebook that I found, his name's Bill, he and I were best friends, right? And he talked me into it. He said "We're gonna go to Vietnam together. We're gonna go on the buddy system." Back then they had a buddy system, you go in the service with your friend, and I wanted to be military police because I wanted to be a policeman. I wanted to work for LAPD, in fact I was a police cadet for LAPD before I went into the service. So I wanted to be an MP. Never happened. Because of my scores I got put into a specialized training so I was what we call airborne weapons controller.

Paul: 'Cause your scores were high or low?

Randy: High. My scores were high. So I ended up working with jet aircraft, controlling, calling in close air support and being targeted quite a lot because we were guys who were bringing in support for guys on the ground. I was on the ground as well but I was on a hill. So there went that whole thing. And my friend Bill, who talked me into going to Vietnam, never went overseas. He ended up doing his tour on the East Coast, and when he found me on Facebook, and the first thing, he was so guilty. I hadn't spoken to him since I'd been back from Vietnam, hadn't spoken to him for 39 years, 'cause it was like three years ago. And he was so sorry. And I said "I am who I am today because of that experience. I can't imagine who I would be now, because I lived through it, first of all." That's the benefit.

Paul: And we have to thank him because the East Coast was never invaded.

Randy: That's right. He became a male nurse. And then when I came back from Vietnam the whole idea of becoming a cop was out the window, because I had discovered drugs then and I had handled a lot of weapons by that time, and I knew with my disposition, putting a weapon in my hands or having access to weapons was going to just end very badly for me. And my father had given me a handgun for Christmas, which I immediately gave away because then, and even now, I don't like having handguns around, or that kind of thing.

Paul: Give me some snapshots from Vietnam and how, if it did, it began to change you. Or things that affected in you in a way that felt intense or...

Randy: Fear is a major factor when you're in that kind of situation, but what you do is you end up making really good friends, like the guys who I was stationed with who I'm not in contact with now, but that is very important.

Paul: I can't imagine. That's just gotta feel like you want to cling to them and not let go.

Randy: Yeah. Guys save your life. You save each other's lives.

Paul: And they understand what you're going through, I imagine.

Randy: Yeah. Let me tell you something. I remember walking down my street the day after I got back from Vietnam, and as I'm looking at the houses of the people that live on my block, my friend's house, and thinking 'To them it's like nothing had changed,' and for me, everything had changed. I remember thinking to myself 'You don't know. You have no fucking idea what a year is.' A year in Vietnam, or any war zone, as any of these young men that are going overseas now can tell you, is like an eternity. Every day is years long. So I came home and people said "Hey, Randy, how are you doing? Haven't seen you in a while." Haven't seen you in a while, not "Haven't seen you in a fucking lifetime, haven't seen you since your world has been turned completely upside down." Like you missed 'em at the bar last week.

Paul: Describe the fear for me, when you’re over there. When does it first hit you, what does it feel like?

Randy: I was under fire, my first day in country. I was under fire. My best friend Art Castillo, God bless him, got killed his first day.

Paul: Near you?

Randy: No. I don’t even know where he was, and we went over at about the same time. Now Art was my childhood best friend until at like 12 years old I moved out of Pico Rivera. We were Cub Scouts together, his mother was my den mother from the time we were old enough to spit, we were best friends.

Paul: Were you moved out of Pico Rivera because of Dodger Stadium?

Randy: No, it was kind of a move up for us, I think. I’m not privy to that information in terms of what my parents’ financial situation was, ‘cause I ended up with my own room, which I never had before, I had to sleep on the couch before that, and when we moved to Temple City I had my own room. So it was a move up for me.

Paul: So describe that first day in country.

Randy: First day in country landed in camera on bay and it was hotter than hell, and I’m disembarking, coming down the stairs of whatever the hell that airplane was…

Paul: Humid?

Randy: Yeah, there’s a line that Matthew Broderick had in Biloxi Blues where he said “It’s hot. It’s Africa hot.” And subsequently I ended up going to Africa and spent a year in Africa, but it’s like hot, Africa hot. It’s humid, it’s 100% humidity practically, and it’s 110 degrees on that tarmac. And I saw these guys walking that had been in country for a while and one guy had a shotgun shoved down into his pack, another guy had a Bowie knife in his boot, and they looked like the walking dead. I thought ‘What the fuck have I gotten myself into here.’ And as we got to the place we were gonna stay that night, there was a mortar attack on the airfield, which they had many of. And nothing prepares you for that. There’s some perfunctory training but…And then a week later I remember sitting on a bunker after I’d gotten to my place in Pleiku, I was in a Special Forces camp and I was sitting on a bunker with a guy at night, we were getting high, smoking a bowl of weed, and he was from Malibu or someplace. He was from California, ‘cause all the guys in my unit were from New York, but this guy in Special Forces was from Malibu, he was a surfer guy, and we were getting loaded and the vil was about a click from where we were—

Paul: What’s the vil? The village?

Randy: Village, right.

Paul: Is that enemy or friendly?

Randy: In the daytime it’s friendly, at night it’s a free-fire zone for them. Because at night…So we’re sitting there and we’re smoking and we were sitting on top of a bunker and behind us was a hooch, the wall of the hooch was behind us. The bunkers were outside of the hooches. So if there’s a rocket attack you run out of the hooch, you jump into the bunker. So we were on the bunker because there was nothing going on.

Paul: And the hooch is the tent you sleep in?

Randy: A hooch is a hard frame, you’ve probably seen them, it’s like a long hut made out of wood.

Paul: And that’s what you live in?

Randy: That’s where you live. You have mosquito netting and blah blah blah. Look at Platoon. The hooch that they’re in, that’s what most hooches in Vietnam look like.

Paul: My first thought, too, when you described the tarmac, that's the scene right out of Platoon.

Randy: You know how many guys saw that scene and got a lump in their throat? Including me. Guys that are Vietnam vets, who've seen that movie...I didn't have those experiences, I don't know who did, I'm sure it happened but I didn't have that experience, but I did have some of those experiences. And Oliver Stone, he was there. Anyway, so I'm sitting there with this guy and I'm hearing this weird kind of sound when I'm talking to this guy. I look over and he's not there and I'm thinking 'What the fuck?' and his hand reaches up and pulls me off the bunker, off the sand bags, and he goes "Do you hear that? Look up at the wall there." So I'm looking up at the wall and he says "Look, look." And there were bullet holes. We were taking fire from the vil, they had seen the light from the pipe when we were smoking. And they were shooting at the pipe and they were missing, they were shooting high so they were hitting above us. That was the first time, Paul, when you realize someone is actually thinking of killing you. There is nothing in the fucking world like realizing someone has targeted you. Not just in general kill somebody, but you. And most guys, if they have time to think that long, die before they're able to process that. That's the kind of fear that you can live in.

Paul: So is it fair to say that when the fear becomes personal, it must just be so visceral.

Randy: It is then, but you learn that you can't think...If you live any kind of experience like that overseas in a war zone, and guys will tell you I'm sure, after that it's just reaction. Don't think. That's why guys, I'm 43 years out of there now or whatever it is, I don't have those kind of reactions but when I first came back from overseas any loud noises, backfiring, you see it in the movies, it's cliché now, but it's not cliché for a guy who's a vet. You react to those noises. You move. That's why you see guys moving when they hear a noise. And no one who's been under fire likes to hear sudden, loud noises. And you see them moving. Just move, don't think. I'm not an expert on this, I'm just giving you my opinion, and there are plenty of other guys who've been through a lot more shit than I have, so, I'm just telling you how it is for me and how it was for the guys that I knew when I was over there.

Paul: Do you remember consciously thinking "This is changing me"?

Randy: No. Too young. That's a process that older people go through.

Paul: Would you try to bolster yourself with bravado?

Randy: Drugs.

Paul: What were the drugs?

Randy: Speed. They had this thing over there called obi, obisitol, you would take if you knew something was gonna happen, or even if you didn't, you would take obisitol. And there was a lot of opium, smoked a lot of opium, and then just the regular weed over there was like the strongest weed you'll ever smoke. It was like smoking Thai stick, just regular Vietnamese weed, very hallucinogenic. And everybody had a nickname, my nickname over there was Lizard.

Paul: Why?

Randy: I don't know. I have no idea how I got it. But I was the lizard, we had Boach, Lizard, the Rat, we had all kinds of guys who had different names.

Paul: I can't imagine a worse drug to be on when you're getting shot at than weed. The paranoia of weed...

Randy: You smoked that at night. You don't usually smoke it in the daytime.

Paul: Jesus Christ, I'm afraid what people across the room think of me, let alone do they want to shoot me.

Randy: But see you're thinking like an adult, you're thinking like a person who processes. That's why the fucking draft is for 18-26-year olds, 26 being the latest. The oldest guy in my outfit was 22, I think. You're just not processing. That's why the draft was created, for young guys. You think you're invincible, you think you're invulnerable, you don't think about what does this mean for my future. You don't think that. See, you're thinking with an adult brain, as an experienced adult. That's not how you think over there.

Paul: Did you enlist or were you drafted?

Randy: I enlisted. I volunteered.

Paul: Just because your buddy talked you into it?

Randy: Well I wanted to be a cop, so I had that whole altruistic thing. I was totally fucked up when I was young. I wanted to serve man, I wanted to serve the community. I wanted to be a good cop and then I wanted to be a good soldier and I wanted to use my brain. That was why we chose the Air Force and ended up with the Army and Special Forces. It was so ironic to me that I ended up living with the Army and with Special Forces. Those guys were my guys because we were surrounded. Like I said, we were on a hill so we were the specialized group and then they were a part of our entourage, if you will.

Paul: Were you in Vietnam for the Tet Offensive?

Randy: No. That was in '69. I was there for the move into Cambodia. That was the 101st, the 170th, we were all there for that. That was in June of '70, or whenever that happened.

Paul: And that was secretive, right?

Randy: Well, open secret. I mean, you're moving thousands of guys to Cambodia...

Paul: It was illegal on the part of the President to expand the war into Cambodia, but that was supposedly because the Ho Chi Minh trail--

Randy: It happened overnight. One morning we woke up and there were thousands of other guys camped out around where we were, literally.

Paul: Were you close to the Cambodian border?

Randy: Pleiku is tri-border area, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam. Central highlands. So you have these two countries coming like this, and then Vietnam here.

Paul: And was it because it was close to the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was the supply route?

Randy: Yeah.

Paul: So your mission was to try to disrupt the supply route.

Randy: Yeah. A lot of the stuff I did was top secret stuff, that's why I had a top secret clearance, so there was shit that I don't wanna talk about even now. But arc light missions--I don't know if you know what arc lights?

Paul: No. It's a terrific theater down in Hollywood...

Randy: Arc light we can talk about. Arc lights were B-52 runs. They dropped big, big tonnage on Ho Chi Minh Trail and all of that. So I did a lot of that, that was a lot of stuff that I did, controlling those aircraft and support.

Paul: Do you ever feel guilt or dwell on the cost of that stuff? Or is that just too painful or not worth looking into?

Randy: I've had all kind of guilt, man, including survivor's guilt. I don't think there's a vet who has any kind of a conscience who doesn't have regrets. Sure. Yeah. Why them and why not me? Why Art, first day overseas? My parents and my family didn't even tell me until I came back from Vietnam that he had died. They didn't want me to freak out, especially knowing that he got killed his first day. And then I came back and my Uncle Joe, who's my mother's brother who's also passed away now, we were playing pool in his pool room and he let it slip. He didn't realize I didn't know. That's how I found out that Art had been killed over there. That was when I came back.

Paul: Did you feel anything when you heard that?

Randy: Oh yeah. I freaked out. It was not good.

Paul: Freaked out outwardly or just inwardly?

Randy: Outwardly.

Paul: What did you do?

Randy: 'What the fuck?' You know, got mad. You don't cry, there was no crying back then. You don't cry, you get mad.

Paul: Which, I would imagine, made it very convenient to be a bouncer at a Hell's Angels bar.

Randy: I got into a lot of confrontations when I was younger.

Paul: Before Vietnam?

Randy: No. After Vietnam. Before Vietnam there was...

Paul: I remember you telling a story about the smell of Brut.

Randy: That's right. Well, I used to send back tons of dope to my sisters and friends.

Paul: Weed, or...?

Randy: Weed, in envelopes, not bales. Maybe a couple of lids at a time, an ounce, whatever. So when I knew I was coming back from overseas I was completely hooked on speed. I couldn't imagine living without it, so some guy was doing something like that, and he goes "Put it in a bottle of aftershave," so I bought like $150 worth of this stuff, 'cause they come in these little vials. Little ounce vials.

Paul: It's liquid, the speed.

Randy: Yeah. It's like a medical vial. You break 'em and then you pour them into whatever. So what we would do is we would break them, pour them into a Coke, drink it, and you're up for two days. One little vial puts you up for two days and you were talking the whole time. It was one of those things where you and your partners would sit down and you'd all take speed and you're just waiting for someone to breathe that's talking so you can jump in and start talking. You just can't stop talking.

Paul: What happens when you come down and you crash?

Randy: You smoke opium to come down.

Paul: But you're on duty, right?

Randy: Yeah.

Paul: So what would happen if shit started to go down and you're on opium?

Randy: Take some more speed. But fear is the great awakener. If there's incoming, 122s or mortars or if you're taking small arms fire, you're fucking straight, trust me. It's not like being drunk. I mean, you've smoked weed, you can come out of it. You can't come out of drunk. You can come out of high. Maybe that's a revelation, I don't know.

Paul: So you poured all this stuff in a bottle--

Randy: There must have been a hundred vials at my feet, I just broke the speed open and poured it into the Brut bottle. I just rinsed it out with water 'cause I didn't want to put soap in there to try to rinse it out and the smell never came out. So I got back home with this big green Brut bottle full of speed, and I was home free. But ever since that time when I would smell Brut I would have a contact high and it was like I would start speeding just on the natch. But I didn't think I could live without it, and I eventually poured out...Being back in the world and being on that high didn't work for me. It was too like being back there, I didn't like that feeling. And then there were plenty of other things to do. I was introduced to LSD, this was 1970, and mescaline. There were plenty of other things I could take that were hallucinogenic, that were psychedelic. So I became very hooked on that stuff.

Paul: Was that the most soothing thing to you, when you would come home? What took you to a place where you felt okay?

Randy: Pretending that I was okay was what...I had re-hooked up with an old girlfriend and we would go to the park when I had time off or something, like if I wasn't working. Because I was still in the military, I was still working as a soldier.

Paul: Even though you were stateside.

Randy: Even though I was stateside. I got stationed up in Sacramento, that's how I ended up back in Sacramento. They were gonna put me in an airborne squadron, airborne radar, it's called AWACS in the Air Force--Airborne Weapons and Control System, which is like a--

Paul: It's that thing that spins around and looks for planes?

Randy: I don't know if it's true now but the United States is covered by airborne radar, planes that are flying constantly, that were back then in 1969 because there was still that danger of ICBMs and all that bullshit. So the whole of the US, but mostly the western and eastern coasts, were covered by airborne radar. But I was scheduled to go back overseas to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines, so when I found that out I asked the flight surgeon 'Am I gonna be flying back over Vietnamese airspace?', he said "Yes", and I said 'I'm not doing that. There's no way I'm flying back." 'Cause I knew how many aircraft had been shot down over there, 'cause that was my job. There were a lot of aircraft that were shot down that were never reported. So I said 'I'm not putting myself back over there again. You gotta help me. Look at my service record," 'cause I had been awarded a few blah blah blahs, this and that. And he says "Unfit for flying, cannot sit in a confined space..." Rubber stamped me out of there. But I was headed back there 'cause the war was still going strong in that point, in 1970. It started to wind down and Vietnamization was occurring in '71 and by '75 we're out of there.

Paul: When did you get out of the Army and what was the reason?

Randy: I was in the Air Force, I got out in 1973. May, 1973, in Wisconsin. The greatest thing that could have happened to me was they thought they were screwing me over so they put me on a radar site, a hundred guys literally in the middle of a corn field in Osceola, Wisconsin, and saved my ass. Mexican kid from East LA and I ended up with all these white people in the middle of America, and learned to eat Bratwurst and corn on the cob and drink beer and play underhand fast pitch softball, and tractor pulls and going to the fair and seeing Neil Diamond at the Minnesota State Fair in 1973, I was working on a farm for a summer. It was good. But my top sergeant and the officers there hated my guts. I was the only Vietnam vet on the base when I got back. They hated that.

Paul: Why?

Randy: They thought that all Vietnam vets thought they were hot shit, that was their mentality. And so "You're not gonna come on to my base with that Vietnam veteran bullshit and act like you fucking own the world." So my top sergeant, he was a seven-striper or a six-striper, he just had it in for me and so I was always catching shit from him and he tried to make my life hell. But even with that it still was great. I loved living there and it was a great time. Learning to drive into the snow. Turning into the skid. Plugging your car in at night. I never knew any of that. You know, a tank heater? What's that? That was an experience, coming back from Vietnam and driving to Wisconsin in January of '71, driving to Wisconsin. I grew up in California, I had a California car. Heater didn't work, tires were bald, so everything was fine until I got to Iowa and got caught in a blizzard coming out of Des Moines. I didn't know shit about turning into the skid. So I thought the magic thing is to buy snow tires, so I bought snow tires. Fifty bucks apiece, didn't help me a bit. I drove out of this town and going north up to Wisconsin, just getting past the tree line, 'cause you know all these small towns have trees that they line the streets, they were windbreaks. Of course I didn't know that then, I just thought it was for looks, but realized later that those trees helped break the wind, especially when there's a blizzard. As soon as I got past those trees the wind is blowing my car and it blew it literally across the road and there are cars coming the other way. I turn away from the skid, my car goes into a 360...Are you from the Midwest?

Paul: I am, I'm from Chicago.

Randy: Okay, so you may or may or not know this, in Wisconsin and Minnesota and places like that, out in the country the roads are built almost like a dyke system. The roads are higher than the corn fields--

Paul: So the banks from the blizzard--

Randy: Then they have ditches with culverts and things--

Paul: That's where you wind up when you're drunk.

Randy: Exactly. But the snow all accumulates there, which is kind of good. So you're literally, it takes the snow a long time to catch up to the road. Anyway, the snow was already almost at the level of the road. I go off the road and my car goes down through the snow, and I'm buried. I'm in a white-out. There's snow all around me, I had to force the door open and crawl up through the snow to get out. I was in that town for three days in a church. I was late to get to my base to my assignment for three days because I was stuck in the snow. I learned a lot about snow.

Paul: So let's fast-forward to when the violence began and your temper began to get out of control.

Randy: Well, probably in '88--

Paul: So a long time.

Randy: Well you said "Out of control." There was violence all through that time. I started working at that Hell's Angels bar in the '70s.

Paul: What brought you to that?

Randy: Because I was working in martial arts and one of my senseis was the manager of that bar so he brought me in. And then I was doing judo as well back then so it was the perfect place to be for me. Plus I got all my drinks for free. And I ended up being a bartender. I bartended. I was bartending when I came back from Vietnam, I ended up getting a job in the NCO club as a bartender. That's what started my bartending career. So I was bartending all the way through until I got clean, up until '88.

Paul: So were you intimidated when you were the bouncer at that, or were you just running on testosterone, or...?

Randy: There were probably times when I was in a little fear, see there wasn't a lot of violence there. There was the threat of violence. Guys would go in there, prospects would go in there, and it wasn't all Hell's Angels. There were guys that were in the Hell's Angels and guys that were prospects that would go in there and sometimes there would be violence and sometimes not, but if there was there were a number of us that were there to handle it.

Paul: It wasn't a TGI Friday's.

Randy: No. You were seeing mostly guys in leather jackets and jeans, long hair and bears and shit. Kind of like ZZ Top.

Paul: Not a lot of them order cheese sticks.

Randy: No.

Paul: So give me some snapshots from that time period.

Randy: It’s very hazy for me ‘cause I was drunk a lot, I was high a lot, with a lot of different women. I did that until I graduated from college, and then I worked for Club Med. See, there’s that whole Club Med life that we haven’t talked about that I spent five years doing. It wasn’t violence, it was just out of control drinking and partying.

Paul: The Club Med thing. And how you didn’t die from syphilis is beyond me.

Randy: It’s amazing. And I’ve gotta tell you, I remember being in Africa, in Senegal, where the President was last week, in Dakar, that was one place I had spent six months at.

Paul: There was a Club Med there?

Randy: There was a Club Med right on the coast, outside of Dakar, a short drive on the coast. It’s called SIDA in French, it’s a communicable disease, it’s got a French derivation. I had never even heard of it. But I was sitting around with a bunch of other GOs, those are employees of the club, and this was 1983, maybe ’84, when AIDS was just coming to the United States. That’s when that air steward brought it. They actually found the number one—what do they call him?

Paul: Patient zero.

Randy: Patient zero, or patient number one, whatever, who started in San Francisco going to those spas, mud baths and stuff, and he’s the guy that created that whole epidemic in the United States. But he caught his in Africa, that’s where it originated, in Africa. But I remember sitting down one night with a bunch of guys and girls and we were all talking about this thing called SIDA. And they were saying “Oh, it’s really bad…”. But up until that time at Club Med, and probably a few years after, because it didn’t really become an epidemic for a few more years, but them saying this was bad, blah blah blah.

Paul: So SIDA was AIDS before you knew it was AIDS, I mean HIV?

Randy: No, that was the French name for it. SIDA.

Paul: For HIV.

Randy: For AIDS.

Paul: Well AIDS is technically the symptoms of HIV.

Randy: Not full blown. I don’t know. I have no idea. But in any case, yes. This was a hint that things were going to change, but everybody kept passing partners around. That was the thing about Club Med, having multiple sex partners.

Paul: Plus people go to Club Med, to fuck. To get a suntan and fuck and forget about their lives.

Randy: That’s right. And there was a lot of that going on and I was a major part of that wherever I was. It was a wonderful time if I’d have been sober enough to have enjoyed it more, ‘cause I traveled around the world. I worked in Mexico, worked in Africa, I was in Tunisia and in Dakar, Senegal. And then I lived in Paris for a while. Worked in Greece, Italy, so it was a good time. But then my drinking got heavier and heavier and my attitude got worse and worse and worse, and eventually they fired me. Such an ignominious fate for me, to be fired from Club Med for being too crazy. That was bad.

Paul: So what happened after Club Med? You came back to the States?

Randy: I came back to the States and my French girlfriend followed me, which was a big mistake. Chantal, she was from Paris. In fact her last name was Paris. That went very bad, and that was in ’84, and within about five months of that my mother went in for a simple operation on her ankle. She had broken her ankle, they were gonna put a rod in her leg, so she went in for that and they over-anesthetized her and she died. Well, she was brain dead, and that was really the beginning of the end for me. In Vietnam and in other war zones you’ll find that nobody dies on Christmas Day and nobody dies on New Year's Day. I don’t know if you knew that or not, but Americans don’t die—

Paul: They’ll push it one day or the other.

Randy: They’ll push it one day ahead or behind, and my mother died on January 2nd of 1985. I was really doing a lot of drugs and drinking a lot, and I was having one of those Twilight Zone moments in my life almost every night where I kept thinking that the phone was gonna ring and it was gonna be my mother saying “Where are you? Why didn’t you come and see me?” Because I remember her calling me right before she went into the hospital, saying “No one’s calling me. Don’t you love me?” And you’re so disconnected from your feelings, I was so disconnected from my feelings, let me become more personal, that I just said I would come and I never did and boom, she was gone. So then there was a law suit, and it went on for three years and we settled it in 1988 in March or February of ’88, and then in April of ’88 I was struck sober. I had a moment of clarity and changed my life.

Paul: Describe that day.

Randy: The day that I realized that I needed to get some help? I had a girlfriend who was like a starlet, she was a former Miss Iowa, how ironic that is, she was trying to make it in Hollywood. We had met at Stanley’s, a drunken night at Stanley’s, and she was beautiful and I was at the end of my life. That life.

Paul: Getting in a lot of fights?

Randy: I actually did wake up a few times with blood on me that wasn’t my own. I would come to in the morning and there would be blood on me and it wasn’t mine—

Paul: And you didn’t know how it got there?

Randy: I did not. There was that, that’s true. And I can’t even tell you about those experiences because I don’t remember them but they did happen. And she was one of those experiences. Woke up with her the next morning and there she was, and then we ended up starting to have a relationship , and found out later that she was having a relationship with a producer and had been lying to me about that and blah blah blah. So I was sitting in my studio apartment up on Sherman Way and we had gotten a settlement from my mother’s death, that was after three years of haggling, so I had money. My dealer, his eyes got bigger than plates when he realized how much money I had. Here was the plan—he was gonna take my money, he was gonna buy all this drug, and I would never have to buy drugs again because we were gonna live on the profit, solely the profit. I would get all my money back and then I would be able to live on the profit from all the sales of all the dope that he was gonna sell for me.

Paul: How could that go wrong?

Randy: How could that go wrong. So I had a new bag of dope, cocaine and weed, and I bought one of those lucky bottles of vodka that don’t break on impact, made out of plastic, we talked about that before I think. So I’m sitting in my studio apartment on my bean bag chair and a voice came into my head that said “You’re done.” It wasn’t my voice. You know how sometimes when you’re loaded you hear your voice talking to you? Or a voice that may not be your voice but it’s a familiar voice? It’s that interior dialog voice? But this was a voice I had never heard before, and it said “You’re done.” And it was scary but I knew I was done. And I had all this stuff. I literally was loaded to the gills, I was ready to start another run. At that time I was a part-time actor and a full-time drunk so I was a member of SAG so I called SAG—Screen Actors Guild, for the uninitiated—and they said call this number, it was Studio 12. There was Tom Key on the other end of the line and he said “Yeah, come on down here.”

Paul: This was one of the first rehabs in Los Angeles--

Randy: Recovery houses, yeah.

Paul: --specifically for people in the studio system. Actors, musicians.

Randy: Yeah, there were a couple of famous guys and girls that went through there before I went there and I’m not gonna bust anybody’s anonymity there, but I walked up the front steps and there was this big guy and his wife and they had two teeth between them. And they were like “Hey, come on in, welcome to Studio 12.” I was like ‘Oh my God, what have I done.’ All they needed to do was if they were wearing raincoats it would have been perfect. It was like a nightmare, like ‘Oh my God, what is going on here.’ But my life began to change that very day. It was a re-birth day.

Paul: I was thinking as you were describing that voice coming into your head and saying "I'm done" and you had all the stuff in front of you...I had a similar experience in my life in that all the stuff that I thought would make me happy and fix me just made me realize even more how empty I was inside and that I needed something else, and I can't help but think that you saw it in black and white--'I've got my drug dream come true.' And on a certain level you realized 'This isn't gonna lead anywhere but eventually I'm out of that money and I'm even more fucked-up.'

Randy: I don't know that I was that insightful.

Paul: I don't think it's even necessarily conscious but sometimes our brain and our soul can figure things out that our conscious mind can't.

Randy: Yeah, I'm sure it was my soul that was speaking, coming through. There was no reason for that to happen on that day at that time, for that voice to come into my head.

Paul: And you've been sober since that day.

Randy: Yeah, since that day.

Paul: So talk about what you've learned about yourself and how you carry yourself in the world since getting sober. What were the revelations to you? And the changes that began to take place?

Randy: I realized that I'd been lying to myself and to a lot of other people about who I was and I realized that I had buried who I might have been under a ton of fear, and I think and I believe, really, that recovery is about recovering the true essence of who we are. It's kind of like when you think of recovering a body or recovering people from a disaster. We are recovering, and I have been in the process of recovering the original Randy. Who that kid was as a youngster who had a joy of life and was loving and caring and wanted the best for himself and others. I had totally just put a lot of distance between who that person is and who I had become. So it's really about finding out why am I like this? What has made me this way? I did not accept who I was. I didn't like who I was. I really hated myself, and why not? I think it would be so beneficial if there was some way to take a spiritual snapshot of people before and after, because a lot of people slip back into that old behavior because they forget where they came from, what they were like. And I don't ever want to do that.

Paul: I like you have that saying, our first day that we come in, we should have a photograph around our neck so in case we start to get any attitude somebody can go--

Randy: "Let me see that photo again." I got that idea, I think it was my daughter when she was doing soccer, they take those photos when they do soccer, it might have been at school, there's a picture of her and she's totally crying. We couldn't get her to stop crying because that's just where she was at, so they took a picture of her crying. And I thought, what a great idea, to take a picture of people before and after. Because a lot of people think they're all that after a while. I'm a blue collar guy and I love what I do today. I'm able to do what I do today because I'm clean and I'm not that guy anymore.

Paul: And your essence isn't weighed down by 50 layers of shitty coping mechanisms.

Randy: My coping mechanism was fight or flight.

Paul: Or fuck.

Randy: Well, that too, but that's also kind of a flight.

Paul: Yeah.

Randy: That's a flight from emotional responsibility. Even today I carry my backpack, you see me, I always have my backpack with me because that was how I lived my life. It's a metaphor for my life, it was a metaphor for my life before, because if I couldn't carry it with me I didn't want it. I didn't want to own it. I wanted to always be able to say 'F-you, I'm outta here. I'm done.' And I did that. I literally did that to a couple of beautiful women that I was living with, we had a fight and I just walked out. I'm gonna be 12 years married. To me that's just amazing, and I love my life today, and I love who I am today. I love my wife and I love my kids and I want what I have. That's the trick, really, wanting what you have, not so much having what you want. Wanting what you have.

Paul: Couldn't agree more. But you can't get there intellectually.

Randy: No, you cannot. You cannot think your way into it, you have to act your way into it.

Paul: You have to act your way into gratitude, and often that means getting outside of yourself and caring about another human being.

Randy: And for me, getting married was incredible, having a child, that really changes everything. At least for me it did, and I think anyone with children will know what I mean, and if you're married and you have a wife that you love you'll know what I mean. I never thought that I would ever be married. I didn't get married until I was 51. I never thought I would have a child, didn't have a child until I was 56. So I never thought that would happen for me because I was too selfish and I was too unable to have a lasting relationship.

Paul: What do you think changed?

Randy: When I met my wife, the first date we had, we talked about having a child. I think I was ready for the responsibility. That is probably the most important thing.

Paul: That's so funny because I would think what a red flag that these two people are so far down the road, but clearly it's worked out.

Randy: Look, I have a spiritual adviser and others close to me at the time, who when I told them I was getting married they were like "You're what??", 'cause I was the bachelor, no way Randy was getting married. And then I told them we were having a child, and that was a process. We went through a few years of miscarriages and things like that, but eventually God brought us our child. But I look at my life today and the good and the seemingly not good is a blessing. Just a total blessing.

Paul: Expand on that, because I know some people will be like..and I agree with you, but help the person out there who doesn't believe or understand that "bad things" can be blessings.

Randy: Well there's the obvious "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger", there's that obvious answer. But also part of that saying is it makes you appreciative of what you do have, and also it's taken me years to come to the conclusion that not everything is permanent, you know what I mean? Feelings are not permanent, situations are not permanent. There are conditions that can be permanent, if you're injured in some way, or--

Paul: But how you feel about it may change.

Randy: That's right. That's what's not permanent. It's your feelings. And that has taken many, many years of going through it and then realizing...I saw in a movie, something had happened and one of the characters said "Why didn't you tell me that was gonna happen?" and the guy says "Showing's always better than telling." So knuckleheads like me, we learn through experience, that yeah, it is gonna change. What I think is really bad now...Even Vietnam, worst experience of my life at the time, but after a few years of being away from it, has been addiction, being in that is the worst thing and then being freed from the bonds of that addiction as long as I maintain a spiritual balance, is a blessing as I look back on it, as long as I don't put it away. As long as I don't turn my back on my past. That's the key, to remember the good stuff and the bad stuff, and the bad stuff, yes, it happened, but we moved away from that. We can recover from that.

Paul: That's why I always harp on how important support groups can be 'cause therapy is great for certain things but there's nothing like sharing your experience and your shame with somebody else who's also lived that and seeing that recognition in their eye that they're not bad, their life has just been covered up with unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Randy: Absolutely. That is very important, to know you're not alone, or you're not the only one.

Paul: What a revelation, what a feeling.

Randy: I think when I first got clean, that was probably one of the...although at the time I couldn't process that, but knowing I wasn't alone, that I wasn't the only one who had lied, not the only one who had done horrible things to people, to myself as well. What is normal? That's always a question.

Paul: I was talking with someone the other day about--it was a bunch of us from the support group, we were having dinner--and I was saying that people that haven't lived a certain experience, that haven't experienced the feelings of your lowest lows and the shame and the guilt, you don't feel like they can ever fully understand you and see you 100%, and the people that do, because they've lived a similar experience, there's a bond that you feel like you've been through a type of war, like you've been in a type of a foxhole. And I immediately felt guilty after I said that because that's a disservice to people who've been in actual war. So I guess I wanna ask you as someone who's been through both the internal battle of addiction and the external battle of being in a war, is that a fair analogy or does that denigrate what--

Randy: No, I don't think so.

Paul: Not comparing it to the horrors of war but just in terms of that bond that you feel with somebody else because you've been through this internal battle in your head where you want to die. You hate yourself so much you want to die.

Randy: Well, you're asking about parallel versus correlation, I think. There is no parallel between recovery and surviving a combat experience, but there are correlations. There are connections that can be made, there are analogies that can be made that are legitimate. Why him and not me? That's the biggest one. We do that all the time in recovery. I've been over 25 years clean and there were guys--and you've heard me say this before--that knew more guys or helped more guys than I ever will, and they're loaded or they're dead now. Why are they? There were guys when I was overseas that went left and should have gone right, that were in that hooch and they might have been outside with me, or they went there and I didn't go there, and they're dead and I'm not. Or they got stationed here and I didn't and they're dead and I'm not. So there are those kind of correlations. Does that make sense?

Paul: Yeah, it does.

Randy: But there's no direct parallel, there isn't. There was a director named Sam Fuller and he directed a few World War II movies, The Big Red One, Steel Helmet, and somebody asked him once "You make your war movies seem so realistic. How do you do that? And all your war movies, would you say they're like war, that they come close to the war experience?" And he said "Let me tell you how you make the war experience come home for a person who's going to a movie. You go to the drive-in where they're showing a movie about war. You go up on a ladder behind the screen, you drill a hole through the ladder, you put a rifle through the hole, and you snipe at the people while they're watching the movie. That's how you make a war movie real for people. A war movie is not war." That's pretty simple. It's like a woman can tell you about having a baby, but you ain't never gonna feel what it's like if you're a man. Never. You can draw correlations, you can say the pain is like...You can make an analogy, the pain is like...You've heard that before, it's like having a watermelon come out of your ass or whatever. But until you feel that pain...I have made those analogies.

Paul: Is a watermelon coming out of your ass considered a fruit baby or an ass baby?

Randy: That I don't know. I think that's interpretive.

Paul: One of the things that those of us that know you quote often is your phrase "Be shut up. Just be shut up because there are times when the world doesn't need to know your opinion. Somebody doesn't need to know that they're wrong and you're right."

Randy: I think in a marriage situation or in a spousal situation or in a relationship situation, that is really for a long-term relationship you've got to make some hard choices. There are a lot of surrenders that have to be made, and most of the surrenders are about your ego. Am I right?

Paul: Totally right. And if you've been raised with the movie version of what a man is, your skin is crawling.

Randy: It almost killed me. The John Wayne image of what a man is, hard drinker...I was raised on Bogart and Wayne, and that almost got me killed. You're absolutely right. It's the image of what is a man. In this day and age, I teach high school today, and their favorite put-down is "Hey, bitch!" That is probably the cruelest, most demeaning thing you can say to a man, and it's almost a sure-fire way of getting your face hit or getting a reaction. What an incredibly intelligent way to get at somebody, and I'm being facetious here. If you call a man a bitch, "Hey, bitch", and I hear it all day at school when guys are angry or they're yelling at people. Because it goes to your manhood. Think about that.

Paul: And it's not so much that you're saying "You're a woman and women are bad", you're saying "You have no manhood."

Randy: Absolutely. But you wouldn't want to call a girl a bitch either. Just calling someone a bitch, period. But to call a man that, you hit it right on the nose. That's probably the most demeaning thing you can say to a man because men like me who've been raised with the idea of what a man is, it's very ego-deflating. And like I said, I'm in my 12th year of marriage, how did that happen? You have to make surrenders, you have to compromise.

Paul: And I think also to have compassion for that other person and to let go of the idea that it's your job to mold them and guide them, which is something that I lived under the illusion for the longest time that 'She just needs to know that this is the right way to do this.' And you don't realize that that takes away that person's trust and love for you. I'm just now getting to that...Getting sober helped because I was able to see what my flaws were because I had to, to stay sober, so now I begin to apply that in my marriage. But it takes time because that hot anger comes up into your face of "She's taking my balls away," and that can be really fucking hard. And my favorite word when I get into it with somebody on the ice--I don't even go to "bitch" I go to "cunt". 'You fucking cunt.' It just feels good coming out of my mouth, and as soon as it comes out I'm like 'What are you doing?' Now I may not do anything to stop it but that little voice in my head since I've gotten sober says 'You're better than this, this isn't who you are. This is your fear speaking. What are you afraid of?' And that's one thing I think I've learned in having to get sober is when that fear comes up, when that thing that the red flag comes up and I know that the right thing to be doing is to go get reflective and say 'What am I afraid of? What did I learn when I did that work on myself with things that I'm afraid of? Are one of those at work here?' And it's always that I'm not gonna get enough, I don't have enough, I'm not enough, I don't matter. Really, really deep--

Randy: Well, you're lucky if you have enough time to think about that between the time you call that guy a cunt and he either punches you out or hits you with a stick. If you're able to process long enough to say "Why did I say that?" and BOOM! You wake up looking at the ceiling.

Paul: My other favorite one is to beg them to hit me. 'Please hit me, please. You're too big of a pussy to hit me.' And the whole time I'm watching myself going 'What are you doing? You're a child. What are you doing? What are you hoping to win from this?'

Randy: Your manhood. Some sense of respect.

Paul: What does being a true man involve that you never realized?

Randy: Consistency. There are so many facets of what my definition of what a man is. Someone who's not afraid to cry, someone who's not afraid to say 'I'm wrong, I'm sorry', like I told you what I thought a man was almost got me killed because I was raised with, in many ways, negative role models. And I think getting up and going to work every day, doing your job, providing for your family, and even if you don't have a family, just being self-supporting. That is part of what it is to be a man.

Paul: Or at least trying to be self-supporting. There's a lot of people that are struggling to be employed, but I think as long as they're making the effort to get employment that's--

Randy: And like I said at the beginning of this interview, not being afraid to say 'I want love and I want to love.' Just saying it, that's crossing a line right there. It's breaking down a barrier, being able to verbalize those feelings.

Paul: Yeah 'cause that's getting vulnerable. 'I have a need to be loved.'

Randy: It's one thing to say 'I want to love' but it's another thing to say 'I want love', for a man. For a guy like me, for someone to say 'I want to be loved, I don't want to die alone. I don't want that and I don't want that for anyone else, either. I don't want them to die alone or to feel that they're alone', and if there's any way I can show that love to somebody else, not all the time, but at chosen moments when you can express to someone 'Hey, you're not alone. I love you.'

Paul: Thanks, brother, I love you.

Randy: I love you, man.

Paul: I really do love Randy. He's somewhere between an older brother and a father figure to me, and he's one of a half dozen guys who have profoundly altered the course of my life for the positive by their example as much as their words, so I'm glad I got to share his life with you guys, or at least as much as we could cram into an hour and a half.

Before I wrap it up with some emails and surveys I want to remind you guys there's a couple of different ways to support the show, if you feel so inclined. You can support us financially by going to the website mentalpod.com and making either a one-time PayPal donation or my favorite a monthly recurring donation, God bless those of you who are recurring monthly donors, it's super easy to set up, you've just got to set it up once and then as long as you don't cancel it or your card doesn't expire it kicks me some money every month, anywhere from five to 25 dollars. Anyway, I really, really appreciate it and five bucks may not seem like much to you but it adds up and it means the world to me. You can also support us financially by shopping at Amazon through our search portal, it's on our home page on the right side about halfway down. You can support us non-financially by going to iTunes and giving us a good rating, writing something nice, that boosts our ranking, brings more people to the show, and by spreading the word through social media. We've noticed a little bit of a bump from some Reddit traffic and somebody has created a sub-Reddit page. It's reddit.com/r/mentalpod. So please go there and check that out, start spreading the word. Get off your fucking ass and chip in, that's what I'm saying. Somebody sent me an email at Facebook that said "Stop swearing, it's not cool." First of all, it just made me laugh 'cause it's like do you really think A) that I'm unaware that I swear and that it might bother some people; and B) do you really think the way that you send that message is going to influence the choice that I'm gonna make? Like I'm gonna go 'You know what, that person with that prickly, terse sentence really got through to me. I think I'm gonna change the way I go about things.' So I sent him an email back and said 'You know what would be a better idea? Stop listening. How about that, instead of trying to control the way I express myself.' And I love constructive criticism but take a fucking second and put it in a way that shows at least some human decency to the other person. I had this moment that pissed me off listening to somebody else's podcast. And there was a guest who I like very much comedically, and had listened to her podcast before, and then she made this comment in her interview where she said that she was a feminist and then literally, 15 seconds later, she basically said that all men are children and aren't that bright. And I just remember thinking 'Fuck you. Can't you see how hypocritical that is? That as a woman you want equality and then 10 seconds later you put all men down?' And I also happened to be going through a period where I was feeling very boy-like because of all the past shit that was coming up with me, so I know I was in a really insecure place. And I wanted to email her and unload on her and I didn't because I was like 'This is my shit', so those of you that want to tell me to swear less, that's your shit, so I don't know what to tell you, but stop trying to change the way I express myself. And the other thing I forgot to mention is you can support our advertisers. I know there's no advertisers sometimes for episodes, like for this week's episode, but if you visit their website when we advertise them that greatly influences whether or not they will advertise with us again and that helps keep the show afloat, so I would love it if you would do that. And I forgot to give the link out for last week's advertiser, which is Onnit, so I just wanted to give it this week, it's onnit.com/happyhour. So if you could go there and check it out and maybe even buy some of their stuff, that would be awesome. They have some really great health products, some of which I'm already using and loving.

Alright. This is an email I got from a listener who calls herself J. She writes "Hi Paul, I'm listening to episode #118. Kulap Vilaysack is the bomb and it has made me so desire that feeling of being in your body. I've slowly realized it's not something I have and I think I'm gonna work on that as well as being present in warding off my anxiety. I had a thought, though, about the babysitter survey you read. I feel like recently I've heard you telling people to forgive themselves a lot. I'm listening to your archives out of order, though, so forgive me if the recentness is my imagination. Hearing you it feels almost triggering to "grant them forgiveness" so offhandedly, and none of my sexual shit happened in childhood. I wish that you would just add some nuance there as in "Yes, that was wrong, but you should forgive yourself," or "I don't know if it fucked with your sexuality, maybe it did, but you were a kid and you should let go of the guilt, maybe not the lesson you learned from it, i.e. respecting other people's privacy or whatever it may have been." It would be great if you could just keep an eye too on whether you forgive women more quickly than men. It sounds to me like you might, and I just hope you're not perpetuating the kind of mentality about gender and sexual assault that over your lifetime has contributed to you suffering longer and getting help later than maybe you had to. Thanks for all you do." Thank you so much for that. And she writes "And stop beating yourself up for stumbling over words, it's endearing and we like you." And I appreciate you saying that, J. And maybe I am more forgiving of women that do that. I don't know. In my heart I don't feel like I have any more judgment for men or women who abuse, but who knows. And thank you for putting that in a way that was unlike the person that Facebooked me and was a dick.

This is from the Shouldn’t Feel This Way survey, filled out by a guy that calls himself Disenfranchised. He’s straight, he’s in his 30s, was raised in a pretty dysfunctional environment. What would you like people to say about you at your funeral? “He taught me to see things from different perspectives.” How does writing that make you feel? “Like a failure.” If you had a time machine, how would you use it? “I would watch my parents in their final arguments before their divorce.” I’m supposed to feel grateful about what I have, but I don’t. I feel unworthy. I’m supposed to feel like I know what I’m doing about fatherhood but I don’t, I feel clueless. I’m supposed to feel like all I need to do is take things one day at a time, but I don’t. I feel like this is impossible.” How does it make you feel to write that out? “Frighteningly nice.” Do you think you’re abnormal for feeling what you do? “I’m abnormal in everything I do.” Would knowing other people feel the same way make you feel better about yourself? “If that were possible, yes.” Well, I say it all the time and I don’t lie when I say it, you are not alone in that. I read so many people’s surveys that express that exact sentiment, so I hope that brings you some type of comfort.