Episode notes:

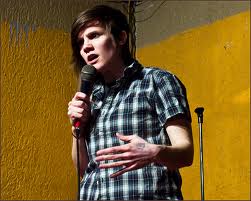

Visit Cameron's website www.cameronesposito.com

Follow her on Twitter @cameronesposito

Episode Transcript:

Welcome to episode 130 with my guest, Cameron Esposito. I’m Paul Gilmartin, this is the Mental Illness Happy Hour, an hour or two of honesty about all the battles in our heads, from medically diagnosed conditions, past traumas and sexual dysfunction – yeah that’s right, I’m throwing that in there – to everyday compulsive negative thinking. This show is not meant to be a substitute for professional mental counseling; it’s not a doctor’s office – it’s more like a waiting room that doesn’t suck. The website for this show is mentalpod.com – go check it out, there are surveys you can take there, you can join the forum, you can read blogs, you can support the show, and you can email through that. You can also email me directly at mentalpod@gmail.com and @mentalpod is also the Twitter name you can find me at. And I want to remind you that Podfest is coming up next month, we’re about a month away, and the website for all the information about that is LAPodfest.com and I’m going to be doing a show. I don’t know who the guest is yet but I’ll be doing a show Sunday October 6th from noon to 2PM but Podfest is that entire weekend, that Friday, Saturday and Sunday. It’s at a great venue and it’s right near the ocean in Santa Monica in beautiful Los Angeles. I kinda like that voice… Yeeeeah, I’m gonna kick it off with an eeemail… No I hate that voice.

This is from listener Roxanne, and she writes: “Hi Paul, for the first time while listening to your podcast I had to end early. I felt your guest crossed a line asking me to empathize with rapists and pedophiles. I wish I could ask David this question.” She’s talking about last week’s episode, number 129 with Dr. David Hirohama. He is a clinical psychologist who worked for a year and a half at Coalinga State Mental Hospital in California. She writes, “Is it true that I’ve read that male sexual predators report an extremely high rate of being victims of childhood sexual assaults but the percentage drops dramatically when they are told will be given polygraph tests to confirm their honesty. Isn’t it true that much more influential is their unwavering sense of entitlement to other people’s bodies which drives their sexual assaults? He gives me the creeps when he refers to a judge who would lock up a rapist or a pedophile as a bad judge. Ick. I’m still a big fan and owe you a huge thank you. Through you and your guests’ encouragement I have redoubled my efforts to get my prescription straightened out and have finally found groups to attend as an incest victim. The group makes me feel amazingly okay rather than ashamed. Don’t get me wrong, there is still tons of painful work to do, but now I feel I have a strong foundation on which to build. Thank you thank you thank you.” Well, you’re welcome Roxanne, and I appreciate you guys giving me honest feedback. One of the things that is hard sometimes about doing the show when you’re used to doing stand-up comedy—you know, stand-up comedy you know where you stand with the audience but sometimes when I put stuff out there I don’t know how it’s going to be received and I think this next one is a perfect example where you can see the gambit of how different people are affected differently by the same episode.

This is from somebody who didn’t disclose a name or an email, and they write, “Paul, I’ve been a Mental Pod listener for 18 months now and I’ve loved every episode. I have yet to miss one, which is more than I can say about any other podcast I listen to.” Oh, that’s very sweet. “I haven’t communicated with you before but have considered it, and after this most recent episode I felt compelled to. I really did not appreciate the Dr. Hirohama episode. The fact that everyone he talked about was an offending child molester or rapist meant that it left out a massive portion of those people, those who don’t offend. There are so many of us non-offending pedophiles and our existence is one that is marked with constant longing tempered with control and can be absolute torture to face. I wake up day after day wishing I didn’t have this monster to hide, knowing I’ll do anything to not hurt someone, knowing that no one will ever know or give me a pat on the back for how hard I try. I attempted to talk to a counselor once about this but he brought up how disgusted he was by pedophiles and I immediately tamped it back down. I’ve never spoken of it since.” By the way, shitty fucking counselor. Shitty fucking counselor. He should be ashamed, or she should be ashamed of herself, whoever that counselor was. And I am giving you a pat on the back for living with that monster inside you and not acting on it, and I know many of our listeners are as well. Continuing. “I think there are a lot of us that listen to your show, sad lonely men and women”—and thank you for including women by the way. It pisses me up when people assume that all pedophiles are male.—“…sad lonely men and women who are cursed to lead sad, lonely lives no matter how much therapy we go to or medications we take. All the words about pedophiles are like this or ‘gosh, I just don’t get how they can be so horrible’ and the Dr. Hirohama episode felt like a knife was being inserted right into my soul. I’m lumped into that category despite all I try to do and I know you are not doing it purposefully but I felt hurt by what I heard the two of you say. I have obviously not left you a way to contact me, and if for some reason you want to continue this conversation, please feel free to mention something on Twitter, the blog or the show and I will get in touch again. Please keep doing what you’re doing. I am sorry, I suppose, for what I am and for putting the weight of it on you but I think someone should say it.” You are not putting the weight on me by saying that. This is the kind of feedback that I think can only help the show. The more diverse experiences that we get to hear about on this show, the better the show has a chance to be, so I appreciate that. I think—I wish people would make a distinction between pedophiles and people who have pedophilic thoughts, and I would put you into the latter category. I think there is a huge difference between pedophiles and people who have pedophilic thoughts. So that’s what I say on that.

Let’s get to the interview, huh? Motherfuckers. Wow. Did I really need to say that? Umm. I’m going to take it out with a Happy Moment. This is filled out by Eileen and she writes, “I remember Father’s Day where I took my father to his favorite restaurant when I was maybe 14 and it was just him and I and I got my dad’s unconditional listening and his full attention which was always very limited, and we had a wonderful dinner together. That instilled in me to always do one-on-one time with your son and daughter where the attention is on and really listening to them.”

[SHOW PREAMBLE]

PG: I’m here with Cameron Esposito, who is a stand-up comedian. I think we met the first time I saw you at Bridgetown, the Portland comedy festival.

CE: Right.

PG: Like two or three years ago.

CE: Yeah, that would have been a couple of years ago.

PG: Yeah, and I was just immediately struck by how personal your comedy was and I just like the way your brain works.

CE: Oh gosh, thanks! That’s probably the nicest thing you can say to a comic, right? I mean, isn’t that what we’re working for, is just to figure out how to be more and more personal?

PG: Yeah.

CE: Because, like, when we get there, then that’s what people can’t replicate.

PG: Exactly.

CE: Right? That’s what we’re being hired for.

PG: That’s what I like to get, I like to get a sense of the human being behind the jokes. The jokes are always certainly great and they have to be there but, you know, that’s what—we were just talking about Richard Pryor a couple of episodes ago and that’s what always made his comedy so great to me was I got a sense of who he was as a person and the funny was on top of that.

CE: Yeah, absolutely, I mean really we’re only talking about, like, four things. All comics only ever talk about four topics, so it has to just be your vision that is the specificity.

PG: Society, religion, your parents and fucking.

CE: Yeah, there is nothing else!

PG: And death, and maybe death.

CE: Right, which might also be about your parents, or could be religion… Or fucking, depending on what kind of death you’re imagining for yourself. (Chuckles)

PG: My first—well, my only CD was called Sex, Religion and Death, because I was trying to figure out, what am I going to call it, and I looked at every bit on it and it was like, they all fall into one of these three things.

CE: Yes! You covered it.

PG: And if you think about it, if you were raised Catholic, how can you not be obsessed about sex, religion and death?

CE: And I was raised Catholic so I know what you mean.

PG: Then here we go!

CE: Now we’re about to start. I also was the theology major in college.

PG: Really? Where did you go to school?

CE: I went to Boston College, so a good Catholic school on top of that.

PG: Oh my god. Are you from Chicago?

CE: I am from Chicago, yeah, I’m from Chicago originally.

PG: Whereabouts?

CE: I’m from the Western suburbs, right near Hinsdale, Western Springs. Like a really nice picket-fencey…

PG: That’s a lovely area.

CE: It’s a super-lovely area. How do you know it? Where are you from?

PG: Well, I’m from Homewood.

CE: Oh, sure!

PG: But my brother lives out kinda near there and I’ve just, you know…

CE: I didn’t know you were from Homewood! How adorable! Look at us – we have many of the things in common. Yeah, that’s where I’m from.

PG: So I’m glad you’ve agreed to come do the podcast, and I’m just really interested to hear more about your life and your story. Where would be a good place to start? What was your family life like?

CE: Sure, well, I guess we’re already talking about where I’m from so we could give that a little bit more of a full… color.

PG: Can I ask how old you are?

CE: I’m 31 years old, but I’m very youthful-looking because of being a lesbian.

PG: And the side-mullet.

CE: Yeah, it makes me look like a 15-year-old forever. Um, I’m 31 years old and I, yeah, grew up in just a really, I mean, super-white area. There was one black family and everybody else was pretty white, and like, pretty white. And pretty Catholic also, area, and really close family – my family is Italian. People sometimes are confused because I have a last name that might sound like it’s Mexican, plus people think my name is Carmen, but yeah, I’m an Italian Catholic suburban girl. But my parents were both from these really conservative Italian Catholic families.

PG: You’re not related to Tony Esposito, are you?

CE: Unfortunately no, because I’d be richer since he is a very successful hockey player. (Laughter) But no, not those Espositos, they’re doing great. Good job, those Espositos, but that’s not me. And what else to say about growing up? Well, I was a little gay kid.

PG: When did you know?

CE: Not until college really. Because there was just nobody who—there was nobody around who was—I mean I bring up the race thing because that’s was kind of emblematic for me of the lack of difference, you know? There wasn’t racial diversity, there wasn’t—I mean it was even pretty taboo to have divorced parents, although I had a bunch of friends who had divorced parents but because I went to such a Catholic school they had, like, an after-school outreach program just for kids whose parents had been divorced that you had to go to, and it was very… stigma.

PG: Yeah, I don’t know if I knew of any family, growing up, that had divorced parents.

CE: Isn’t that wild to think about, with what’s actually happening in the world, and—

PG: And I also don’t know if I knew of any family that had happy parents.

CE: I was just gonna say.

PG: Happily married parents.

CE: So my parents are—I don’t get the sense from them that they are, like, stuck together and miserable. They’re really different people but they also have been together for—this will be their 40th wedding anniversary, and they really like each other a lot, I think, in this way that is—like they’re very bonded, I can see that they are choosing to still stay together, even 40 years in. But that is not everybody’s parents that I knew growing up certainly, and I think you’re right, yeah, it’s a lot of like—

PG: ‘We’re gonna stick this out.’

CE: A lot of ‘we’re gonna stick this out,’ yeah.

PG: Which, you know, when you’re doing it for the kids on a certain level I have such respect for that, but I think it depends on how badly you don’t get along and how well you can kind of hide it from the kids – I don’t know if hide is the right word, but—

CE: Or even—no that’s a great point. I also think if you can have separate lives and both be happy in that way, because I guess that’s kind of—as my sisters, and I have two sisters and as we’ve all gotten older and we need our parents less I’ve seen that they’ve just continued to be branching out and having more full lives each individually, and I think that’s another thing, that if you’re stuck in an unhappy marriage for the kids, like, please go do something that does make you happy. That’s another thing I saw a lot, people that were spending a lot of time hating each other.

PG: Yes, and kids really tune into their parents’ unhappiness, and a lot of kids—because kids instantly blame themselves, think ‘what can I do to make my parent happier?’ and that’s such quicksand.

CE: Absolutely! And I also think that if your family is really—so I didn’t have that, but I had kind of the opposite of that, which is that because my parents are, like, together, and then… My dad is adopted into his family at a time when that still would have been pretty controversial, like in a Catholic Italian family, for him to be adopted in the ‘40s was like a failure for his parents in a way, and also really great for them – I mean, they were great parents to him but it was like he was carrying—it’s different now. Not that it’s not still something that kids and parents have to process together but it’s just like not so much a negative thing.

PG: Right, it wasn’t like an interracial couple in the ‘50s in the South. (Laughs)

CE: Right, exactly, yes! (Laughs) So he was carrying that into our family and then also my mum wasn’t super—wasn’t always very close to her family geographically or even emotionally, and so they created this family of their own that was like blood and really close to each other and so my closest friends in my whole world are my two sisters and my parents, which is a weird thing for anybody who’s in their early 30s to say, I think.

PG: That’s kind of sweet, though.

CE: It is sweet. It’s also the opposite of what you were saying, because you were saying it’s a big burden on the kids when the parents are miserable. It’s also a big burden on the kids when the parents are, like, they just love you so much… And that’s okay, but like, for instance, it was a real risk for me to move here to L.A., because I have always kind of been meeting their expectations of being physically close by in case they needed me.

PG: That’s such a double-edged sword because it’s so nice to feel wanted and important to them, but there’s this weird line that some parents cross – and I’m not saying that’s the case with your parents – where the child begins to feel as if a part of their life is being lived for the parent, and that the parent doesn’t have a life separate from them, and I think that can really be kinda smothering and kind of fuck with your head a little bit, because it’s like, I don’t know, it’s like intimacy in a bad way. You know, it’s like a neediness instead of intimacy.

CE: Well also—how old are you?

PG: I’m 50.

CE: Okay, so there’s also an interesting maybe generational gap here between you and I in that people that are my age, like, our parents also—it’s that hyper-scheduling.

PG: Yes, the helicopter parents.

CE: And then all the things that that translates to for the rest of your life, so like if your parents need to take you to 75 soccer practices, then when you are 20 they still kind of think that they need to take you to 29 soc—you know, it’s like, you know, my parents come to shows and stuff, and it’s cute, I’m happy they’re there but I also don’t—you know, it’s my job, so I don’t really need them to be there.

PG: Do you feel like you want more breathing room from them?

CE: I feel like I’m so glad that I live here because it has actually improved our relationship.

PG: I always say that the reason that I settled on Los Angeles is, that’s where I hit water.

CE: (Laughs) Exac—well—the thing is, I felt like I was always trying to kind of run away from them when I lived in Chicago—or I lived in Boston for school and then some years after there but it was kind of like this idea that I was trying to tell them to leave me alone so I could live my own life. Now that I’m here there is such a great physical distance that I feel a lot more comfortable being the one that is reaching out, and I don’t feel like I have to—like they can’t just show up at my house, even if it’s just to bring me presents, which is very nice, but they can’t show up at my house. So then I call them a lot more, and actually our relationship is really great right now.

PG: And are you excited then when you go home and you get to see them?

CE: Yeah, it’s a little bit intense because, again, I have—so I mean I lived on the same block with my two sisters before I moved here, and my one sister is married so her husband as well, we like all lived on that same block. And…

PG: Your home?

CE: No, downtown in Logan Square, which is like a really hip neighborhood in Chicago. But half hour, you know, half hour drive. And then my parents would come down a lot because we were all located so close together. I mean, I feel like every day I could have gotten a call that was like, ‘Hey, mum’s over at my house,’ and then I have to go that sister’s house, or my dad’s at my house and they have to come to me or whatever, and it was just very—it is really nice to go back there but it’s also, now all that in like four days as opposed to a lifetime.

PG: What was the attitude in your family and your neighborhood about gay people.

CE: So, two nights ago—well, first of all, I’m enfianced, I’m engaged to a fabulous woman who is—

PG: Congratulations.

CE: Thank you! She is also a comic, she’s great, and she—I don’t know how this came up but two nights ago we realized that I had never seen the puppy episode of Ellen which is where she comes out. I’d never seen it because I was remembering that I wasn’t allowed to watch it. So that is the attitude. We’re talking two nights ago. It’s that episode of her show where she comes out, 15 years ago.

PG: Okay, not her talk show, her sitcom.

CE: Her sitcom, yes, of Ellen.

PG: It was huge. It was a huge deal when it happened.

CE: Huge deal! And Oprah’s in it, which I—because I had never seen it, I didn’t know. It’s actually this crazy moment that really made me—I literally cried when I was watching it because I was thinking at the time that maybe Oprah must have been, I mean, she was like—who could you get there to be a more powerful woman to be in that show? Because they have her set up Ellen’s therapist, and then Ellen says like, ‘I just want someone to tell me that it’s okay that I’m gay’ and then Oprah leans over and actually physically touches her, she puts her hand on her thigh, and she was like, ‘Ellen, it’s okay.’ And I was thinking, I mean, basically it was like, when that episode came out it was like they got God to come and say that to her. You know what I mean? Like who could they have gotten that would have been more influential. So anyway, a shout-out to Oprah. Good job, girl! I’m so stoked that you were a part of it. But yeah, I wasn’t allowed to watch that show.

PG: Did your parents say why? That episode or that show?

CE: I think she came out as a person before she came out on the show, so I remember when she came out as a person, then I was not allowed to watch it. And I was also not allowed to watch Rosie O’Donnell’s talk show. Or, like, I mean I was a teenager, like I was a teenager when this was happening.

PG: Wow.

CE: One time there was a kiss between two women on like the Video Music Awards or something.

PG: Yeah, I remember.

CE: I mean, it was super sensational, like it was not a—

PG: Yes, it wasn’t passionate, it was more like a novelty.

CE: But I remember my dad walked in, and the VMAs were just on, and he like walked into the house and saw that I was watching it and he told me to turn it off. So…

PG: And get out of the room so he could jerk off.

CE: (Laughs) No, because it was a sin! I mean, maybe, but—

PG: So your parents were pretty hardcore Catholics. Are they still?

CE: Uh, well…

PG: Does it come from their Catholicism or does it come from their kind of societal—

CE: You know, I think, so I think the first thing is, when your kid comes out to you, then you have to acknowledge that your kid has sex of some kind, any kind ever, and I think that’s always weird for any parents. And then especially the societal attitude toward homosexuality. I can came out 10-12 years ago and in that span it was such a different thing to say that you were gay because there were still no representations of happy adult couples or marriage wasn’t a thing that was legal yet at all, people weren’t really talking about the possibility of kids… So I think my parents were really—they were worried that I was choosing to ruin my life, it’s something that we talked about a lot.

PG: (Chuckles) That one always just baffles me.

CE: Well, but I mean a part of me—because I also grew up, like, drinking the water where they were living at the time, I understand why you would think that. I mean, why you would think that you would be ruining your life. I think that for a kid when they’re coming out, what’s happening for them is they’re about to enter the happiest part of their life because now they finally make sense to themselves, and for a parent you never lived any of the horror that is not knowing why are you so weird, and so you just think your kid is feeling fine the whole time. Then they come out and that’s when the terror starts.

PG: They think it’s turning for the worse and the kid knows it’s turning for the better.

CE: Exactly, so it’s the exact opposite experience I think that parents interpret for the kid who’s coming out. It’s the exact opposite experience.

PG: That’s such a great way to put it, that’s such a great way to put it, I’ve never thought about it that way. What’s it like having that secret inside you? How many years did you have it inside you before…?

CE: Because I had no models for this being a thing, I just thought that everybody felt the way that I felt, like I thought that all—because I had really close female friends in high school, or even in grade school, but then I also dated men, and I just thought that everybody… And also the funny thing is, because we teach women that their sexuality is so much more fluid than men – and I don’t even know if I actually believe that, I believe that’s part of a construction that we’re putting on women. ‘Oh, you guys can be fine with whatever.’ So I really thought that everybody was fine with whatever, you know what I mean? Because Cosmo is basically just writing articles where it’s like, ‘ways to jerk off your guy, also if you want to have sleepovers with your best friend, here’s like a…’ There’s no clarity in how you’re really supposed to feel, or what you’re truly feeling I guess is what I’m trying to say. So I just thought that everybody was super grossed out when their boyfriends were kissing them. (Laughs) Just want their boyfriends to go home immediately. I thought that’s how we all felt. Then at the same time I was drawn to… Okay, I remember watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer because there was a character on there, Willow, who was like a gay character. And I remember my high school boyfriend being like, ‘Why do you like this show so much?’ Like, I remember I was trying to wear my hair like her hair and stuff. I just like, ‘I don’t know, she’s just great, she’s just rad. I think she’s just like a really funny person.’

PG: And did you know that that was why you were attracted to her then?

CE: I had no idea! I mean, it was so confusing. Looking back on it—so I kissed a woman for the first time when I was a sophomore in college, and that moment was… I describe it to people as like that moment in Signs. Did you ever see Signs?

PG: Uh-huh.

CE: There’s like aliens—you’re trying to watch the movie in reve—or like the movie Memento where it’s like, he has tattoos but he doesn’t understand what’s going on, and then at the end there’s like ‘oh’ – an M. Night Shyamalan twist and they solve all the… That was what it felt like, I felt like I was getting all these clues my entire life and then I was like 20 and then I suddenly realized, ‘Ooooh! You’re totally not—you’re not heterosexual if you have all these songs that make you think of your best female friend, and no songs that make you think of your boyfriend, and you’re not heterosexual if you think your boyfriend is really esthetically interesting but you also are an outspoken advocate of abstinence because you don’t really care about sleeping with him.

PG: (Laughs)

CE: Because I was in high school.

PG: How convenient!

CE: I know, I know! And I was never really judgy about it, but I just remember I would always be like ‘We’re waiting…’ Which is so funny to me now.

PG: (Laughs)

CE: I’m so sorry to all those poor girls that I…

PG: But you probably spared yourself a lot of really uncomfortable moments where you wouldn’t be true to yourself.

CE: Yeah, and I mean, I actually didn’t end up waiting, I did have sex with men, and it was… I mean it wasn’t—I guess at a certain level human contact feels good.

PG: Yeah.

CE: So there was that element to it. But then the first time I was with a woman I understood what the difference it.

PG: The passion on top of the friction. (Chuckles)

CE: Yeah, like, it’s probably what it’s like to kiss somebody on screen for a TV-show versus kiss the person that you’re choosing to sleep with that night.

PG: Right, and you know, people that have been sexually violated say all the time on the podcast, their bodies often respond and they think that meant that they wanted it, which is not the case at all, even in the worst of worst situations people can still experience physical pleasure while their soul is screaming out, ‘This is not right.’

CE: Absolutely, absolutely, and I do stand by that. Also because I think that’s another thing that people get really confused about about lesbians specifically, because so many lesbians so have experience with men, because again so much more is allowed, that when you’re a little kid nobody really yells at you what you are with the same frequency that that happens to gay men.

PG: And who is not going to give it a shot?

CE: Right, exactly, you give it a shot, you try it out, and I think that for some people that’s confusing, like, if you can, or people will think that I don’t understand if men are attractive at all, which is also really hilarious. I’m a human being, I understand that men are attractive, it’s more so, I just think about who I would want to sleep next to, not necessarily who in a moment of looking at them from across the room I would want to sleep with. I think there’s a really big difference there.

PG: We get so many people who fill the survey out who can only orgasm—they identify as straight but they can only orgasm thinking about somebody of their same sex and they have no desire to be in an intimate relationship, you know? So I think there’s all kinds of varieties of, you know, what turns you on esthetically, what turns you out emotionally—

CE: Absolutely.

PG: —and people should give themselves a break on trying to force it into different things and just go, ‘Hey man, I’m beautiful, I’m unique, what makes me cum makes me cum and fuck anybody that doesn’t get it, as long as I’m not hurting anybody else or lying to somebody who’s close to me, you know.

CE: Yes, and if we could be more open about that, I mean this is—I think one of the reasons that you initially contacted me was that I had recently written something about how I really prefer to watch gay male porn than anything else – if I’m ever watching porn, that is what I’m watching because to me that looks a lot more like my sex life and I think it is because for some reason the way that it is generally shot, gay male porn is… Like, there may be some dominance going on but there is also… Often the dudes are like a similar size to one another or they actually have erections so you can at least tell yourself in your mind that maybe they’re enjoying themselves.

PG: Right.

CE: You know? I know that sounds nuts but—

PG: I don’t think it sounds nuts, it makes perfect sense because I think for a lot of people feeling aroused is that you want to know that the other people are enjoying themselves. I’ve heard women say that they don’t like dick pics but what they do enjoy is a picture of an erection in the context of that man being turned by the woman he’s with, and that they find erotic.

CE: Yeah that’s really interesting, wow. That’s actually really interesting. Yeah I think that’s 100% true and so often because I’m a woman, what is happening in porn to women or with women I know wouldn’t really be pleasurable for most women, because men are generally the creators of porn and so a lot of times we’re watching something that a man thinks another man wants to watch and it’s like… I don’t know, I mean why is that even in there? It’s just—I have to turn right off. It super grosses me out. So…

PG: Can you be more specific about what the vibe is of it? Is it that there is—

CE: Sure, I’ll tell you. Yeah I can give you the vibe. I think that it’s the amount of participation that that person seems to be having in their own body in that moment, which again I think kind of goes back to the erection thing. Yeah you can take a pill and kind of fake that but there’s also like a physical representation that it’s working for you, and a lot of these women—like, if they’re touching themselves in a way that is like, just like, there is a lot of weird slapping that happens, and things like—like, her face is first of all not seeming really into it, and then also her body is clearly doing something that must not be awesome for her. So I’m always wondering about the direction that she’s getting from over there and I wish that she was getting direction from inside of herself.

PG: I feel like a lot of the porn that I have seen is kind of the equivalent of the stripper pole dancing which I have never found attractive. It has always felt like this is her idea of what sexy is, but she’s not—she may enjoy the feeling that she is turning other people on, but it has never been sexy to me, it has always felt like bad gymnastics. The sexiest I’ve ever seen, you know pornography or being in a strip club, has been where there’s a subtlety to it, and it’s the look on her face and what’s in her eyes, and she doesn’t have to do much at all – it’s about her body language and the way her eyes move.

CE: I was also going to say, you know what else kind of can make that more a factor for me is that you actually get to see the transaction that’s happening, you get to see that somebody is paying that person to do what they’re doing. So on some level that also kind of adds a participation that you get to see from that. Because like, okay, she is doing something and I’m hoping that she’s safe, you know, that’s something that I’m always going to look for. Have you ever been to strip clubs in Portland, and there’s like a very safe and comfortable esthetic going on there that kind of takes care of some of the problems that I might have if I walked in and I was like ‘Please, somebody, get a van, we need to get all these women out of here!’ (Laughs)

PG: I would imagine a lot different than what you would feel in Tampa.

CE: Yes, exactly. So these women have made a choice, and then they’re also getting money, so fine. I’m fine with that. They know they have a job, they’re doing their job and it’s immediately rewarding for them, but something like a video clip on the Internet – I have no idea what happened to the woman before she was right there, and then if the actual thing that I’m watching is also something that seems dangerous or seems like it wouldn’t be sexy to her or pleasurable in any way.

PG: It almost feels to me like when you see bad comedy that’s really loud but isn’t saying anything, that’s what bad porn feels like to me, where’s there’s just a lot of energy being expended but there’s no kind of authenticity to it.

CE: (Laughs)

PG: And you know, the times that I have been at a strip club – I don’t go to strip clubs anymore – but when I used to go strip clubs I would always be aware that this person would rather be someplace else making money, but given that, there could still be a certain amount of enjoyment that she’s doing her job well and that she’s proud of her body and that she’s proud that people find her attractive and what she does, she does well. That’s the most that I could ever kind of say, ‘Okay, this is as real as your fantasy-ridden head can get.’

CE: Yeah, I completely agree with you. It’s that overt, ‘Yeah, that’s her job, she’s at work, she’s doing a good job and therefore she gets rewarded. And it’s so funny that you brought up the bad comedy thing. (Chuckles) Because you’re right. Bad porn, bad comedy, never knows when to stop. It just keeps going, tries to find that button that works.

PG: It’s like bad improv too, where it’s just desperate, there is a desperation to it that is really—it’s like a train wreck that actually winds up making me sad.

CE: That’s such a good word for it, because especially since—the reason I’m talking about women with this is because there’s another thing happening which is that men in life are not as desperate as women are in terms of their safety. So watching a guy get fucked is really different than watching a girl get fucked, even if you know that that guy may or may not be gay, he may or may not be having the time of his life, like when he leaves the studio then he still gets to be a guy and maybe not worry about alleys so much. But that woman has to leave the studio and she has to have whatever happened to her and she also still has be a gal that’s just trying to navigate the world with the inherent unsafe feelings that you have as a woman.

PG: I think the mistake a lot of men make and what the mistake I made for much of my life, is that, you know men are so genital-focused and I think they assume that women must be to a certain degree as well, and they think how can a lesbian be turned on by an erection and then not want it outside of that situation. Because men can’t imagine that.

CE: I know, I mean I get that. So that’s why I’m saying I think it really is about power dynamics and about the fact that those men—I’m watching two people that are powerful in some way that are interacting with each other and that’s not necessarily always present with the women. And then still, because it’s a human body, it is pretty and interesting and then on top of that, if you are lesbian you are into women but you also have grown up in a super-duper straight world, so you still are invited to sexualize a penis. I mean, it’s not like if you’re lesbian nobody has ever told you before, like ‘Hey, have you thought about looking at men?’ You’ve spent your whole life kind of living in between two worlds, one of them being the world that you associate yourself with and then the other being the world that you’re dropped into, and so I also think there’s an element to that there. I mean, just the idea that we gay people still talk about things like tops and bottoms, or doms and subs, or like ‘who’s the man?’ is something that still comes up for people, and that’s because that’s the majority of the world we live in. All the TV, all the pictures, all the art, it’s like everything we’ve ever seen so of course that’s there.

PG: The first time I saw—I don’t remember if it was a clip or it was just a picture but it was of a she-male and I got a feeling inside of me that was so uncomfortable. And I’m okay with it now, and I don’t think I’ve ever even masturbated to it but it made me so insecure because—

CE: Do you know why?

PG: Well, because I thought that must mean that a part of me is gay. And it took reading something or hearing somebody say that a lot of straight men are turned on by she-males, and… But I remember thinking to myself, I could blow that, that woman or I don’t know what the pronoun would be for that, and I had never… I don’t know if I could, but the thought of it was erotic to me, and I had never felt that way about a penis before.

CE: That is so interesting. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard Dan Savage speak on that point. Have you ever heard him speak on it?

PG: No.

CE: So, Dan Savage, sex-based columnist, his over-arching view on that is that gay men are never attracted to she-males. That that is actually only for straight men that want to also encounter a penis, because gay men don’t want to sleep with a woman, so the whole rest of what that person is presenting to the world is a woman, and then just with a penis which is something, as I said, we’ve all been eroticizing our entire lives. I mean, we also kind of—we’re also sexy with ourselves sometimes, we have appreciation of our own bodies, and so it’s just a moment for, like, attaching to something that is – well not attaching – connecting with something that is yourself and the other thing that you might be into. And I think most gay men are actually not super into that, I think that actually means you’re straight. But I also know that straight men really worry because they hear it a lot in comedy. I know that straight men really worry about—as if there’s like a tally, that if these things, then you’re gay.

PG: Yeah. You’re less of a man – each one takes away from your masculinity, and the older I get the more I feel like no, the more you can be honest about what you think and feel, that adds points to your manhood.

CE: I absolutely think so.

PG: I have to say, though, the part that I think would keep me from ever wanting to – and this is assuming that I wasn’t married – the part that would keep me from wanting to put that in my mouth is the scrotum.

CE: (Laughs)

PG: I just find scrotums…

CE: Me, I love scrotums! No I’m just kidding, GROSS! They’re the worst.

PG: It is the worst! I know it provides a function but it is just the saddest-looking body part ever! Ever. It’s like if there could be a body without a scrotum I might even be gay! If there could be a body without a scrotum. But anyway. Do you want to talk about when you came out? Do you want to back up before that? Was there stuff…

CE: I guess we could back up a little bit, also because—okay, so, yeah I was a little gay kid in a weird place to be that. Not that there’s like a super comfortable place, we’re still in a vast minority. And I also had crossed eyes for a lot of my childhood and I had to wear en eye patch for eight years.

PG: (Gasps)

CE: Which I say just because, I mean, you know this…

PG: 24 hours a day?

CE: No, first 24 hours a day and then it would taper off because I was strengthening my eye muscles, so when I was a little kid—in pictures you can kind of see like they’re just drifting, but it happened overnight, they were just BANG – crossed. I was two and I had to have surgery and then I had to wear special glasses and then I had to patch. First it was a lot and then it was school and then it was just after school and then eventually not at all, but I still have crossing eyes sometimes if I was super tired, like I would go to school dances with completely crossed eyes. And then I had to have a second surgery when I was in my twenties as well, to correct the same problem. And actually, stinky, but it is also coming back now, I’m so bummed about it because I was feeling such a reprieve the second surgery had worked, but it’s just like a weakness that I have in my eyes for my whole life. And the reason I bring this up is because I also think it’s really relevant to being a stand-up comic, which is that you always know, if somebody’s a comic, that they had… Like, what was your thing? You know what I mean? It was like, you had a thing…

PG: What was the torpedo that sank your boat?

CE: Yeah, you had a thing, I don’t know what it is but it was a thing. I really think that—so not only was I awkward in terms of—I’m just wearing weird clothes, I didn’t know how to dress or how my hair should be. Because when you’re gay you shouldn’t be wearing dresses all the time, unless that’s the kind of gay you want to be, but you shouldn’t have to be some sort of bizarre extra from Peter Pan or something. Or maybe Peter Pan himself. I think a bowl a cut… It was bad news. But then also I think the thing about having an eye patch is, you really learn how to cut people off with a pass when you’ve like a very physical thing going on with you. Nobody can ever make fun of you if you are hilarious first. So I feel like that’s something a lot of comics develop, like that thing, that distraction device where it’s like, ‘Yeah it’s crazy, there’s stuff going on on my face, but have you noticed how hilarious this is?’ You know, a kind of diversion tactic.

PG: Yeah. Did your family consider you funny?

CE: Yes. Yeah.

PG: That must have felt good.

CE: It did. Did your family consider you funny when you were a kid?

PG: They did – my brother not so much. I don’t know if he was annoyed by me but my parents did and that was always a big icebreaker for me because there was so much tension between them.

CE: Are you older or younger?

PG: Younger.

CE: Yeah, so, my older sister – I don’t know what the dynamic was between you guys – my older sister was like very, a little bit shy and very cute and very feminine. She was a ballerina, and so I think especially because of what was going on with my sexuality, like, following that. We’re three years apart but we were raised really closely.

PG: It’s like a Todd Solondz movie. (Chuckles)

CE: So it was like, I had to be like, you know what I mean, I knew I couldn’t be that. It was the exact pinnacle of that, you know, a ballerina! There’s a Christmas video that I found a couple of years ago that’s the two of us getting presents, sitting side by side, and she gets elbow-length—she’s ten and I’m seven, and she gets elbow-length gloves and children’s make-up and a tiara. And I got a black Ken, because I collected Kens and it was the one I didn’t have yet.

PG: (Laughs)

CE: So she… (Laughs) So she… You know! It’s so good.

PG: If you saw that in a movie you would be like, ‘That’s a bit much!’

CE: I know, it’s so good! And I’m wearing like a long—she has really long, skinny legs and I’m wearing an over-sized T-shirt that somehow is super tight on my butt cheeks. It’s so amazing. She’s like, ‘Oh my god, elbow-length gloves, I can’t even believe it! How kind!’ and I just go like, ‘BLACK KEN!!!’ Literally the loudest voice you have ever heard come out of a seven-year-old, and I’m dancing around and I turn around and my T-shirt is tight in my butt, you know like just the worst kind of like, chubby and a bowl-cut, I have glasses, wearing an eye patch, I have a tight T-shirt in my butt, I’m getting Kens… Sure, it was a little bit rough!

PG: (Laughs) That’s so fantastic. Of all the tableaus I’ve had painted for me—

CE: (Laughs)

PG: —in doing this show, that is among the best. I think my other favorite tableau was when David Holmes came out to his mom. She couldn’t accept it, and one day she calls him, and she doesn’t even say ‘Hello, it’s mom,’ she just says, ‘What about a masculine female?’

CE: (Laughs hysterically) Oh my god! But yes, that—I’ve gotten some of those calls. They didn’t sound exactly like that, but similar ideas. Yeah. Holy shit.

PG: That is gorgeous.

CE: And then my little sister is very artsy—

PG: Three kids?

CE: Yeah, three kids.

PG: Three girls?

CE: And then my little sister is seven years younger than me and ten years younger than my older sister, so it’s kind of like a huge gap there, so my older sister and I were kind of raised like twins, but the opposite sides of the coin in the most black and white way possible. And then my little sister was just kind of this like—she was always teeny, you know? She was always so little and we could carry her around and stuff and she was very, like, wacky, and kind of on her own vibe always. But a really awesome vibe, but she was just always doing her own thing. Like selling various things at various stands in our front yard, she was always having business, like some kids would have lemonade stands but she was having, like, bracelet stands from bracelets she made or, she just always had to work.

PG: Go-getter.

CE: Yeah, she was a go-getter.

PG: What was your older sister’s attitude towards you, like especially when you were in high school and people knew that you were her little sister. Was she embarrassed by you, was she protective of you?

CE: The funny thing about all of this and all the things I’m saying is that I was never unpopular. And I don’t mean like in a braggy—I mean, it’s shocking to me looking back on it, I really was rarely made fun of, because I did so much of the being boisterous and laughing myself.

PG: You did a lot of footwork.

CE: I did a LOT of dancing, yeah. And the other thing is that I’m pretty shy actually, as a person, pretty introverted, but I can really perform. I really like people and I really like making people happy, so that was always true. I would go home and spend a lot of time by myself and lock myself in my rooms and not want to leave and not want to go out and hang out with people, but then if I was able to leave the house and go out then my personality kind of switches completely and I’m—

PG: So you picked your moments; you weren’t just constantly on?

CE: No, and I’m still not to this day.

PG: I think most good comedians have to have that quiet place to draw from, to observe and get philosophical.

CE: Yeah, I do too. I also—I don’t know how people do it the other… I guess that’s the thing about being an extrovert versus being an introvert, but I just get so exhausted and have to take time in my brain, to slow my body and my mind down because otherwise all will go so fast that I explode. So, anyway, this is all to say that I was just really well-liked because of the performance aspect, and so—

PG: And you have a natural likeability too, you know, I wouldn’t say that it’s all…

CE: Yeah, I’m honest and I care about people, and I always was. I never was, like, trying to—I mean, I don’t know, it takes a special kind of asshole to make fun of the kid with the crossed-eyes who’s like ‘Guys, I have crossed-eyes and it’s pretty hard…’ You know? Because I was always pretty honest about it, and it pretty sad, you know?

PG: Do you think your gener—and this may be a hard question for you to answer because you weren’t a part of my generation, but do you think your generation’s sensitivity towards people with differences was a little greater than ours because of more attention in media about it, with talk shows like Oprah and, you know, more after school specials. Whatever it was, MTV, it just seems like—I’m always shocked when I hear about a kid that came out in high school and had like no problem, or like people were supportive and they were elected prom king.

CE: Yes and no. I mean, I do think there’s improvement and I do think that—I can’t believe how different people’s narratives are about their lives now coming out then even just ten years ago. It is so far apart that it blows my mind. It is so far apart, how controversial it was. I came out at a college where they refused to have a non-discrimination policy about sexual orientation. It wasn’t just that there wasn’t one; they refused to have one. So the university that I came out at could have kicked me out.

PG: And which one did you…?

CE: Boston College. And it was something that they were fighting. They were fighting with the students about this while I was coming out, but there were like ten people that were out, or eight or something, and it’s of a 4,000 or 8,000 person student body – I mean, the percentage is really small. And yeah, they wanted to reserve their right to kick kids off campus.

PG: Is BC a Catholic university?

CE: Yeah, it’s Jesuit.

PG: Okay.

CE: I think they’ve changed that now.

PG: I think Jesuits are a little more progressive too than the other Catholics. They tend to be a little more philosophical and kind of open-minded in terms of, you know, maybe I’m wrong, but that’s—

CE: Yeah, I think you’re right, you’re right about a lot social issues. It’s weird because I went to a school that was very known for its social activism, but about things kind of outside of the student body. I mean, they were also—I was in Boston during 9/11 and the airplanes had left from Logan Airport which is in Boston, that had crashed into the towers. I also remember another thing that was happening on campus was like the very few Muslims that we had were getting stopped by campus police, and things like that. So it’s the same university that would send kids to—like, I went to Jamaica, to inner-city Kingston to, like, pray with people and build a house for them and honestly touch lepers. Like, really, that was a thing, they had programs like that. But then bringing it back home, the pain that their own student body was facing at the time, like a Muslim kid who is just getting stopped at the dining hall or something, with zero reasons, you know.

PG: Wow. That’s awful.

CE: Or like saying that you won’t protect your gay students. I actually think that way about the Catholic Church in general, that sometimes it’s so about the ideas and it’s not about the actual people that are really there in front of you.

PG: Yeah. And that’s usually what changes somebody, is they experience a person in their life and their attitude changes about that thing because they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, these ideas actually affect a human being that I love.’

CE: Yes, and so when you encounter somebody who knows people and it doesn’t affect them, then that always makes me wonder what is wrong with that person. And that is what I encountered at that school, you know, I was like a 20-year-old kid, super confused and having a hard time. I had some professors that were very supportive and I also had some very clear messages from the administration that who I was, was wrong. Those are 50-year-old men looking at a confused, alone 20-year-old girl and saying, ‘You are going to hell.’ The amount of cruelty there is actually pretty substantial, I think.

PG: You know, there’s this certain current running through a lot of Catholic people, and I don’t know if it’s their buried rage at accepting a tradition that they don’t really like but they’re afraid to question, but there is a meanness to certain Catholics that is almost unparalleled. And I’m sure it—you know, because I haven’t experienced other communities like Baptists and stuff like that, that can also be super repressed, but some of the meanest people that I’ve ever encountered are people I meet when I go back home and they are still church-goers and they’re just so racist and they’re so—just mean.

CE: For me it actually goes up to the people that are in power in the Catholic Church too, not just the—because you’re right, talking to someone face to face is very intense but I think that might be the issue with that organization is that they could do so much good. There’s a lot of churches that don’t have the history and the power and the potency and the social currency that the Catholic Church has. The Pope is The Pope, you know? There’s an evangelical Christian community – they don’t have the sides of buildings in Rome and then also the sides of buildings in Buenos Aires. They’ve so much money. They’ve so much land.

PG: He could put out a rap album and it would come out as number 1 on the billboard charts.

CE: He could do anything and it would come out on the top! So I guess that’s what really bothers me about it. It’s like Spiderman – with great power comes great responsibility. It’s one of those traditions that really is still respected generally by the media and by people’s vague familiarity with is, and then to just squander that. I can’t understand it.

PG: And I know many Catholics who are really good Christians who walk the walk and don’t judge other people and are wonderful people.

CE: Certainly.

PG: Talk about your experience in Jamaica, that sounds really interesting. What was that like? What were you thinking and feeling as you were doing that? Give me some snapshots.

CE: Yeah. In Jamaica we went to an orphanage for HIV-positive kids because their medical system there doesn’t necessarily support long-term care, so kids who are HIV-positive sometimes fall out of the system. They can’t stay in their homes, so they would be at this localized facility. And there are leper colonies. Leprosy is actually treatable, it’s curable, so it’s just a lack of the right medicines getting there. And the leper colonies are run by nuns, the same order as Mother Theresa actually. And going there and seeing all this stuff, I mean I feel really lucky that I was able to see just a larger picture of the things that are going on in our world, but it’s also pretty intense for me to think back on that, because I was 20 and I didn’t have really great skills to offer these people. I mean, I had “my concern” and “an open heart,” but what I really wish that I had done was use that money that I used to go down there and instead, if we had hired or paid for somebody who knows how to build a great sewer system, or doctors, people like that to go down there.

PG: Did you make the mistake of asking a leper if they prefer a high-five or a fist bump?

CE: (Chuckles) Have you ever seen—I can’t believe I—have you ever seen a face without a nose?

PG: I have.

CE: That’s a weird thing, isn’t it? I’ve seen it a couple of times here, too, but—

PG: There’s a guy that would panhandle outside Pete’s Coffee and Studio City, and I think he was a burn victim as well, and he didn’t have a nose, and it’s pretty intense.

CE: Because like, it’s always the little things in a human face that you don’t even realize how much that shapes how we interpret everything else.

PG: But yeah, that is something I did during that time in my life, and I hope that sometime when I’m more financially stable in the future, that I could do something that would be open-hearted in that way but also a little bit more responsible and not just like, ‘Hey, here’s a bunch of kids, and it’s spring break, and they’re not going to Mexico, they’re going to YOUR country to help you, and they’re WHITE people!’ You know, there’s a lot of stuff going on.

PG: But isn’t that kind of par for the course for, you know, an excited 20-year-old kid that has limited world experience, that that’s—you know.

CE: Yeah, and I mean I don’t think I went anywhere super arrogantly either, I wasn’t like ‘Hey guys, now you’re fixed, because I’m here.’

PG: I love, by the way, that you went down to build houses in Jamaica and interact with lepers and you’re finding fault with some of that. That takes a special talent.

CE: (Laughs) Well, it feels really selfish to me, it really does. It feels very selfish. That is where I met my first girlfriend, though.

PG: How the fuck is that selfish?

CE: Again, I’m saying, it feels like tourism.

PG: I see.

CE: It feels like tourism in somebody’s life who actually just has to live that life. Like for instance one day I had a little bit of extra money in my pocket, two dollars or something like that, and we were helping this gentleman and his daughter who own a sandal store where they would make leather sandals by hand. And there were little kids that were helping us paint a mural so that the store could look nicer, like we had finished a wall for them and we were painting it. And a dude walked by who were selling plums or something like that. And I said, ‘Oh, I’ll take a bunch of those, how many can this buy? I’ll just take that number.’ And the woman whose dad it was who owned the store—because I had these plums and then I turned around to offer them to the kids who were helping us, and she pulled me aside and she said, ‘Please don’t do that ever again, because I can’t afford to buy plums for these kids and when you come here and do that then you give them the message that, like, some white person from America is going to come here and save them, that they can ask for a hand-out and that they should ask for a hand-out, and also that their community can’t provide for them what they need.’ And so I deferred to her on that because I was really embarrassed and I actually agreed with her. It’s probably very intense to live your life there and then have somebody come in and just be like, ‘Oh, you guys eat fruit? Oh, I’ve got all this money, so, ha ha, I don’t even care!’ You know?

PG: (Laughs) It seems like the last thing that people have that they cling to is their dignity.

CE: As they should, right? I mean, thank god she said that. That’s a great spirit. I’m glad that’s what she has to say, that she’s not saying like, ‘I’ll do whatever you need and you should do whatever you want,’ you know, that’s she’s saying ‘There have to be boundaries because you don’t have to stay here and this is not your community and I don’t want you to be the one that fixes it. You’re half my age and you don’t live here.’

PG: There’s a great book written by a guy who – the title of the book and his name escapes me – but it’s about—he decided to travel the length of Africa over land, not take any flights, and he had been there in the ‘60s and he was comparing how it was different now than it was in the ‘60s, and he was actually against aid, saying that it had made people complacent and he showed all these examples where people had kind of lost the motivation, their entrepreneurial spirit – which I’m sure is incredibly difficult in an impoverished Third World country, but he really came out of there—I think he went in there feeling pro aid but he came out of there thinking, ‘No, this is ultimately something that is really kind of sapping the integrity and spirit.’

CE: Yeah, I think it’s very complicated, right? Because there’s a bunch of different levels that you can help, you know, you can send money that then—who knows where that goes? Or you can physically be there and hand out money and that’s such a short term solution.

PG: Like mosquito netting for malaria, there’s no question that’s an awesome thing. Medicine for kids, that’s clearly awesome, but I think financial assistance to adults in the village, I think that was kind of his point.

CE: Sure, I can understand that. But at the same time, you can’t look at that and be like ‘No, I shouldn’t help.’ It’s just such a complicated—

PG: So complicated.

CE: It’s complicated here when you walk down the street and there’s homelessness here that I’m not used to seeing because in Chicago, I think because of the weather changes the homeless people have to take some sort of shelter at some point, like they can’t stay out all winter long because they would be too exposed to the elements, but there are people who live here on the street year round with no coverage, no shelter, nothing. And then I just have to, like, go to my house with my groceries walking past that person. I don’t know how we’re supposed to deal with these things. That got so serious, but I’m really affected by that.

PG: I’m struck by—and maybe I’m reading you wrong but I’m struck by what a predominant emotion guilt is.

CE: Oh, wow.

PG: Is that a fair assessment.

CE: Yeah, maybe, I never thought about it.

PG: I mean, clearly you’re somebody who’s very, very sensitive and considers others, but I almost get the feeling like you have a hard time being okay with yourself navigating the world because there are other people suffering, as if they have to be mutually exclusive.

CE: Oh, that’s really interesting. Yeah, okay. I think maybe that’s right, I guess I never thought of it like that.

PG: And I get it.

CE: It makes sense to me, saying that. I mean, it’s also what I was talking about earlier, you know, grow up in a family where it’s like sink or swim for everybody, it’s really hard to lose that perspective for the rest of your life and for everybody else that you meet.

PG: What do you mean when you say a sink or swim for everybody?

CE: Well, I was always taught that you do not leave your sisters behind, I mean, literally every night and probably every day for our entire lives. Like still, ‘Don’t leave your sisters behind!’ And I don’t know what he’s talking about because they’re both doing exceptionally well. One sister works for the City of Chicago in this really high-profile arts job, my other little sister is about to move to Argentina, she’s about to move to Buenos Aires.

PG: (Chuckles)

CE: They’re doing really well. (Laughs) They’re in charge of themselves and we’re all really successful, we’re really put together and generally on time and in good relationships and stuff but I don’t know what he’s afraid of. Whatever that is, that’s definitely what I’m afraid of too.

PG: Yeah. What are—shall we go into some fears and loves, or—let’s hold off on those for a while because there are other parts of your life that I want to know about. Tell me about when you met your first girlfriend, what was that like? You said it happened in Jamaica?

CE: It did, yeah. We were on this trip together and she was just another gal that went to BC and we had to do training for our trips where we would read up about the culture for a bunch of months before we would go down there, so as to not put ourselves in danger or offend anybody.

PG: Buy a bag of plums.

CE: Yeah, buy a bunch of plums, yeah. (Laughs) Anyway, so by the time we got to Jamaica we had spent some time together and she was going through a really hard time with her family, which—I really like to hang out with anybody who’s going through a hard time. I don’t know what that is, why I like love—specifically women who are complicated, because I think maybe I’m—

PG: Are you a fixer?

CE: I’m a little bit of a fixer, yes.

PG: Were either of your parents drinkers or addictive in any way?

CE: No, no.

PG: Okay. That’s just a common thing that you find in people that are fixers, like one parents has something they’re obsessive about or can’t control and you just kind of see that a lot so I was curious, but go on.

CE: Well, I mean, I think it is honestly probably part of being the middle child of a very intense family where there was a lot going on between—and actually you know what, I wouldn’t say that there was not addictions going on, I just maybe didn’t think about it this way: food was a really hard problem in my family growing up, and still is. So I think part of that might also be their—a lot of fights about what was the right thing to eat and how much was the right thing to eat, so that does sound like an addiction, doesn’t it, now that I say it.

PG: Mm.

CE: Yeah, and then—

PG: And I’m not trying to pathologize your situation, it’s just a thought that popped into my head.

CE: Yeah, I mean, it doesn’t—I don’t feel that way at all. I guess I just have always thought that… This is going to sound so funny, but I always thought of myself as, like, the—I’m really like the son in my family, so I have always had to keep it together for everybody.

PG: Interesting.

CE: Yeah. Wow, I’m gonna honestly cry right now!

PG: It’s okay, we like that.

CE: (Laughs)

PG: We like that on the program.

CE: Yeah? Is that good?

PG: I’m so uncomfortable I called it ‘program’ right now.

CE: (Laughs) I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to be emotional.

PG: What are you feeling right now? What’s bringing that up?

CE: I don’t even know. I think just… Um. I honestly think it’ll be the first time I’ve ever thought about it like that. You’re here, we’re in this office, we’re above a 7/11. So I think it’s just that.

PG: Isn’t it cool when you have little moments like that where you—and sometimes it’s painful and sometimes it’s kind of, you almost feel stupid for having not seen that before.

CE: Yeah.

PG: But I don’t know, there’s almost like a—there’s like a relief in it for me sometimes when I get more clarity on who I am and where I’ve been, and how I feel about it. Can you talk about...what that little moment that you just had or are having, what it feels like or…?

CE: I think just—I feel, um… Actually maybe angry, which is weird. Guess I didn’t expect to feel angry, but I think I feel a little bit mad about just, like, having to be tough, I think. I think it’s the combination of having somebody tell me – having you tell me – but having somebody tell me that it sounds like a carry a lot of guilt and then coupling that with just actually feeling—yeah, just feeling angry about that.

PG: Do you feel like—well, let me ask you: is the anger directed outside of yourself, towards yourself, both?

CE: Um…

PG: At the universe?

CE: (Laughs) Yeah, I think maybe actually just… Honestly I think it may be at my family, because the thing is, when people are really nice to you, it’s really hard to feel angry with them. Do you know what I mean?

PG: I do, I do. And when you sense that there’s a part of them that’s broken or needs help or they can’t see, and you feel like you know what can help it, you tell yourself as a little kid that it would be selfish of you to not do all you can, but you forget that you’re a kid and they’re the parent and it’s their job to think of your needs and not your job to think of their needs – certainly not when you’re a child and they’re an adult, but kids don’t know that. Kids often step up and become that adult before they should be an adult and it takes a part of their innocence away.

CE: Yeah. Absolutely. Yes.

PG: And I relate. When I got in touch with that anger it was fucking rage. It was fucking rage.

CE: When did that happen for you?

PG: In my twenties, first time I went to therapy.

CE: Yeah, I mean, I have had some therapy myself and I don’t think I felt angry before, literally before today. I think I felt more, like, really smashed. Like really held down. I was in a—

PG: Would suffocated be a…?

CE: Yeah, yes. Yeah, I was in a very serious relationship for a long time that was pretty unhealthy because we had set up—I had set up one of those beautiful fixing dynamics in a situation that—

PG: You had a lot of work to do.

CE: I had a lot of work to do and then also I was pretty sure I had no work to do on myself, you know, how we can set that up for ourselves when—at least I can; I’m really good at sometimes finding—like if I’m going through a hard time, then I find something that’s really intense that is outside of me and then I can think about that. Then I don’t have to worry about my own shit. But that relationship was ending and I felt so terrible because I felt like I had ruined a really—I thought I was supposed to be with her, and so I thought that I had ruined something by needing to fix it so much, not realizing that if there’s that much need and there’s that much fixing and those are already our personalities on top of it, like if the personalities are there and then also there really is a desperate amount of stability, that we were kind of doomed to begin with. But I was—

PG: You couldn’t see that then, though.

CE: Not at all! No, I thought we were supposed to be together forever. And I went to therapy not even understanding why I was upset about it. I was just like, ‘my girlfriend’—because she wasn’t American and she had to go home because her visa ran out, and I was just so sad that she left that I was sad for a really long time. And I’m not usually—I can spend a lot of time being quiet but I’m not usually sad very much. So I was sad for a really long time and then I decided to seek therapy because I was like, ‘I feel really sad and I can’t tell why.’

PG: How dare somebody smite my rescuing superpower?

CE: (Chuckles) I know, exactly, that’s exactly what it is. I felt really sad because I didn’t fix it. I didn’t make it all better.

PG: I would imagine on a certain level – and I’m talking about myself as well as you because I’m a fixer – you begin, especially when you fix adults, it’s a real high as a kid and it makes you feel really special and you don’t know that it’s kind of an unhealthy special. So when somebody looks at that special and says, ‘nah, I don’t want that,’ it’s almost like it’s going to the core of who you are, what you take the most pride in, like ‘I care, I listen, I have good suggestions, I empathize, and somebody is just going ‘no’.’

CE: Yes. And I will say that the reason that I am so happy to be with my fiancée is because she is the first person that—because I found that it was either that, like ‘no,’ or sometimes it was like ‘YES!’ and I didn’t even know that there was an option where somebody could say like, ‘Oh, thanks, not today,’ like where they could pick or choose times that you would help them, and then they would try and pick or choose times to help you. I guess what I’m speaking about is balance.

PG: Yeah!

CE: And equity. But it was not something that I had experienced because I was going in with so much of my own specific need to be that fixer.

PG: That more is better in terms of my fixing because it means I’m a more loving person.

CE: Right, exactly, right. (Chuckles) And also, for myself, I am very hard on myself, but I am also in my own head and I know that I also like myself a lot. I actually think I’m pretty cool, but I also really am hard on myself and hate myself. But I know both of those things and I think sometimes when you’re a fixer, what you can be projecting out is a lot of the negative things about that person because you’re talking about the things that need to be fixed and you’re keeping the good things that you like about them inside because those things don’t need to be fixed. When you’re on the inside looking out you know both things—

PG: Yeah, that’s a great point.

CE: —but when you’re talking about somebody else, you can get really stuck on that, like ‘Hey, you know what you could do better?’

PG: And you forget that then they are experiencing that not as love and caring but is criticism and is saying you’re not the way you should be—

CE: Absolutely, yes.

PG: —and then we’re baffled by the fact that they wouldn’t want our help.

CE: Right. I think there’s a lot of that in the specific place and time and family that I grew up as well, it was very achievement-oriented and very, you know like I said, ‘Bring your sisters along,’ but then also like go to this school and get these grades, and not just in my immediate family but in this very specifically sheltered community of people.

PG: So I wonder if we should ask ourselves when we find ourselves trying to fix that person, to say is this love or is this control that I’m finding myself attracted to, or compelled to try to act on. Because I know for a lot of years I thought that I was “teaching” my wife, “teaching” a friend, and it’s so arrogant in so many ways. And there are certainly times when I think I have been a good friend and a good husband and have been helpful, but I think there are so many times that I thought I was helping and what I was really trying to do was control.

CE: So are you able to ask yourself that question as you’re doing it now?

PG: I am now, but it’s taken a long time, and I hit my head into a lot of walls.

CE: Does it feel bad physically if you have to restrain yourself from helping because you realize it’s control.

PG: No, it feels freeing when I am able to recognize it and say this person is on their own journey, I’m not here to teach the world how to act; I’m here to help when somebody wants help, if somebody asks for a suggestion, or one of those rare circumstances where I feel like it’s okay to say ‘Hey, can I make a suggestion here.’ But it’s taken me a long time to get there, and I think what had to happen for me to get to that place was, I had to get in touch with all of my own flaws and all of my own fears and realize that so often I’m filtering that data of the universe through my own fears and prejudices and my own experience, and that I have to accept that other people are different. And I still catch myself doing that, and I have to not hate myself when I catch myself doing that and say ‘Hey, I’m a work in progress,’ you know?

CE: Yeah. Well, I feel like I’m just a couple of years into understanding that about myself, because I do think that I have those tendencies very much so, and I’m actually just a couple of years into this relationship that has been—you know, met a great person at a great time in my life, after I had started to do some of the digging. Maybe the first—excavating the first eight layers of a possible eight hundred. So I feel much better. I’m so thankful that I did some of that work so that I could be a little bit more able to balance myself out. But I don’t feel like what you’re talking about, that catching yourself, I don’t necessarily feel that yet all the time.

PG: Your fiancée sounds like she has a good sense of boundaries.

CE: Yes, well—see, here’s what’s interesting. She has a family that is very intense, just like my family is very intense, and both of us have been working through therapy and through just growing up and being adults to set better boundaries, so I think both of us are a little bit more aware of it while not necessary having it as our base. And actually that’s kinda nice because she doesn’t necessarily shame me for having these boundaries that—because she also has weird boundaries, so we’re working on it together, and I’ll point stuff out to her too and she’ll point stuff out to me. So that’s a lot better than—I think it’s just nice to meet somebody who understands what the thing is, you know?

PG: And I think recognizing it is always the first thing that has to happen, because nobody is like ‘Oh, I recognize it, and now I’m fixed!’

CE: (Laughs) That’s true.

PG: You know, these are like pathways worn into our brain that we kind of need to rewire, and it takes a long time, it takes a really long time. But I think what you describe the relationship that you have with your fiancée is that’s the best possible setup that you can have for two people working towards becoming more independent and also loving, you know?

CE: Yes. Yeah, I think you’re right. I just hope I’ll be able to do it. I hope I’m able to keep—

PG: I think you are doing it.

CE: (Chuckles) Yeah.

PG: It sounds to me like you are. We didn’t finish touching on your first girlfriend and what that moment was like when you were finally able to be the authentic you. Were you able to be the authentic you?

CE: Well, I mean, we—it was a very good relationship but it was also really—I don’t know that I was able to be the authentic me yet, just because for a part of the time that I was dating that woman I was still dating men casually as well and trying to figure that out. I had a lot of—I initially hated myself after figuring out that I wanted to be with her. I wasn’t like an immediate relief, it was more like—things were really tumultuous with my family and I didn’t feel like I could come home very much because I had to remove that part of my life before I was able to come back, sort of, per request. And so, it just took me years of being kind of in limbo, of having other girlfriends and… And then, after dating women for—I think I had already dated two women, like dated, I mean like been seriously—not dated, like been with, multiple year relationships I’d been partner to them before I was really coming out to people. And I had been doing improv all this time, professionally and also in college, and then I moved back to Chicago. It was right before I had moved back to Chicago I had come out to—I just started coming out to everybody as opposed to just like whoever I felt like it was relevant to, or something. And then when I moved back to Chicago I started doing stand-up, and I really think that part of that was because it was a great way to be able to tell everybody all the time, because I could say it every time I was on stage, and it was something to be, come on, we’re comfortable with… It’s just weird when you’re gay, it’s not something that you physically look like or something that people can necessarily always read on you, so you have to tell them, which is awkward sometimes in conversation, not because it’s strange to be gay but just because it’s a weird thing to bring up your sexuality. Heterosexuals don’t have to do that. So I found stand-up, and I also started dating that woman that I was talking about, that “fixy” relationship. But she was actually very supportive of my being on stage and also of my being on stage and talking about being gay. And that is the first time that I felt like I was working within things that I understood.

PG: What was your family’s reaction when they started hearing you talk about being gay on stage?

CE: It was really bad actually. (Laughs) I remember this time, they brought like twenty friends or something to a show, like my parents brought twenty of their friends to a show. Twenty of their friends, to a show!

PG: I’m not gay, and those are always the situations that I would be the most nervous because I was always afraid of bombing, not because I would bomb but because then they would have to lie to me after the show, and I hate that dishonesty.