Depression on campus

Depression on campus and its countercultural lessons

Guest post by Daniel Jackson

When I began my career as a professor, I never imagined that so many of my meetings with students would end with calls to our mental health clinic. I certainly didn’t anticipate the project that I’ve recently completed.

Shocked by a terrible spate of suicides in my university, and a constant stream of students pleading for help as they struggled with their coursework in the face of depression and anxiety, I wondered what I might do to help.

This is a post in our Guest Bloggers series. All opinions are those of the author. Please consult a professional for medical advice.

Buy the book, Portraits of Resilience.

My university had launched a new initiative to promote wellness and mental health, and there was already extensive counseling support. What was missing, it seemed to me, was a campus-wide conversation about depression and the social and cultural factors that fueled it.

What was missing, it seemed to me, was a campus-wide conversation about depression and the social and cultural factors that fueled it. #mentalillness Share on XDestigmatizing mental illness is important because it lowers barriers to seeking help, and lets sufferers know they are not alone. But in our enthusiasm to label people who suffer from depression as ordinary, we tend to overlook the fact that their experiences, and the insights they have about them, are often extraordinary—that they have, in the words of Kay Redfield Jamison, “felt more things, more deeply; had more experiences, more intensely; loved more and been more loved; laughed more often for having cried more often; appreciated more the springs for all the winters.”

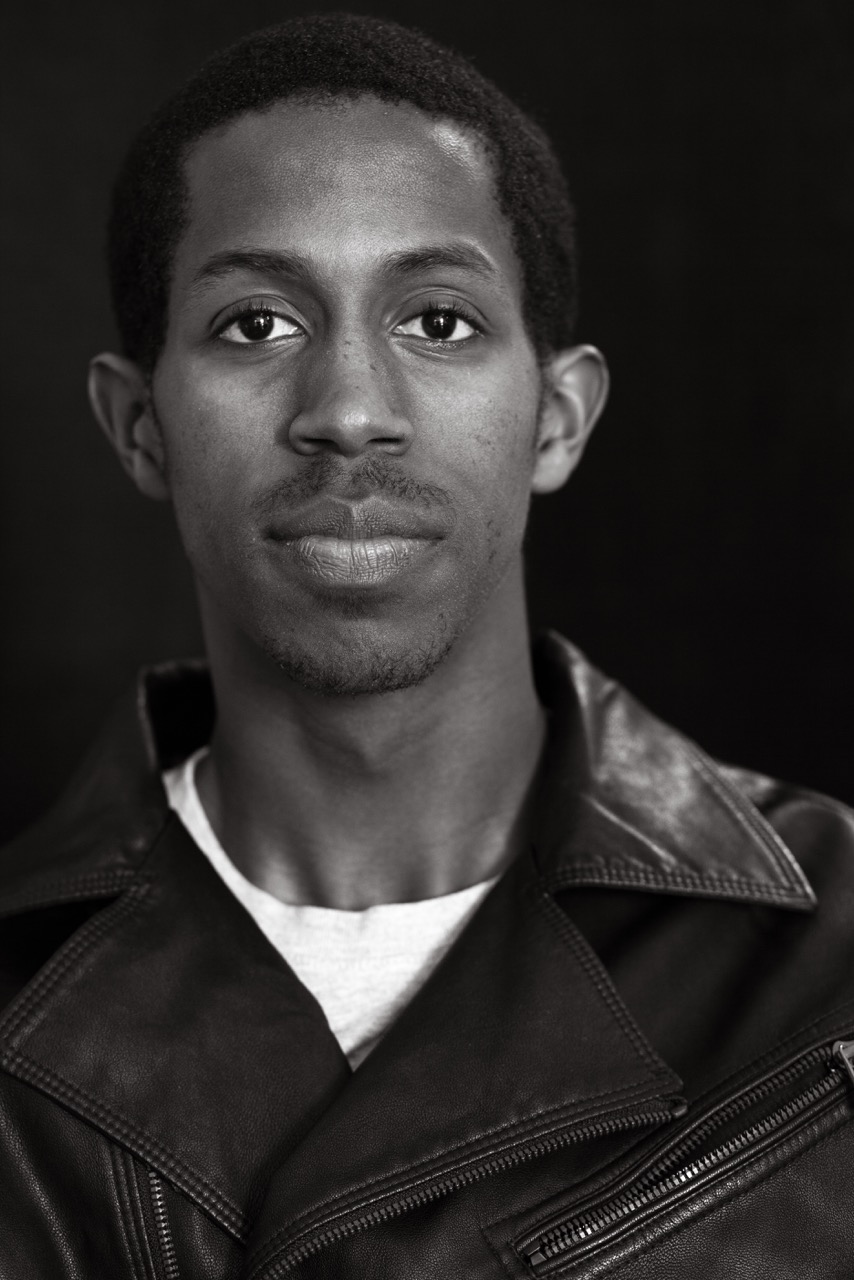

We needed, I thought, not to normalize these people but to honor them: to celebrate their resilience in the face of unbearable pain and to learn from their insights. I, therefore, planned to assemble a gallery of photographic portraits, each accompanied by a brief and inspirational quote. I would publish a portrait each week for a semester in the college newspaper, drawing attention to depression not as an abstract affliction but as a challenge faced by real people.

So I set out to meet students, faculty, and staff who were experiencing depression, anxiety and similar challenges. In a series of two dozen interviews, they told me their stories: how they came to a point of crisis; how they dealt with it; and how, eventually, they were able to come to terms with their problems, or even overcome them.

The brief quotes became mini-autobiographies.

I had wondered whether students, in particular, would be willing to divulge personal details of their struggles in such a public forum, potentially jeopardizing their employment prospects.

To the contrary, their openness, and the generosity with which they shared their stories blew me away.

Krista Tippett, the host of NPR’s On Being, claimed in a recent interview that “younger generations present themselves to the world with a fullness and a lack of inhibition that is new in human history” and that transparency and integrity are “new moral values for a new generation.” My project proves her right. A student with obsessive-compulsive disorder told me about his urge to insult people; one described his first same-sex encounter and the opprobrium he suffered after; another told of her suicidal intentions and involuntary hospitalization.

Many of the stories confirmed and made real my prior understanding of mental illness. I heard repeatedly of the roots of depression and anxiety, in both genetic makeup and earlier traumas. I was told about the good and bad effects of medication—and, from one person, that taking Prozac for the first time was such a profound experience that she “felt like herself for the first time” and that the “darkness and sadness and anxiety that I thought was me was actually changeable.”

Many students told me about the negative impacts of poor sleep and over-scheduling, and that “going against” your depression—by fighting the instinct to withdraw—can be a powerful tool (in combination with other forms of help).

But I also learned many lessons that are counter to the scientific and engineering culture of my university.

People told me again and again how they’d been helped by talk therapies of various sorts, even if they could not explain the exact mechanism, and had to deal with the skepticism of their friends. Spirituality came up often in our discussions as an antidote to depression, along with the realization that religion is poorly understood—dismissed for its dogmatic claims and unappreciated for the sense of love and belonging it can engender. I was also reminded of something I’d learned from my own family’s experience with depression: that our tendency as engineers to try and fix the world is not always productive. One student who had been suffering from Bell’s palsy for six months told me how she finally decided to make peace with her pain and the possibility of never regaining her smile. In place of all her engineering-like interventions, she started meditating instead. To her surprise, her condition began to resolve itself within days.

Perhaps most important were the cultural lessons.

Hearing stories of emotionally abusive supervisors and teachers, I learned how even the smallest comments can have a debilitating impact. I came to see that our desire to reward and recognize achievement does not foster self-esteem. On the contrary, it fuels feelings of inadequacy. Our students’ passion to make a difference in the world is replaced by a constant pressure to meet proxy measures of success, such as high grades, awards, and prestigious internships.

Depression is a terrible disease, but none of my subjects would have chosen not to have it. Without it, an eminent 70-year-old professor told me, “I would have been trying to climb that ladder until the day I dropped dead.” He’s still trying, he says, but it’s balanced by a realization that there are more important things—like being able to get out of bed in the morning.

Daniel Jackson is Professor of Computer Science at MIT and author of Portraits of Resilience. For more information about the project and the book, visit portraitsofresilience.com.

No Comments