A Psychiatrist’s Take On Treating Insomnia

What’s the deal with insomnia?

Nearly everyone with mental illness experiences insomnia during the course of their recovery. For some, it’s the harbinger of a new depressive episode. For others, it’s a manifestation of chronic anxiety. It can occur immediately after drug use or linger for months after withdrawal. But for nearly everyone, this awful state between dead tired and wide awake is one of the most miserable symptoms imaginable.

For many years, insomnia was considered to be just a symptom. (And indeed, insomnia is a common accompaniment to many physical and mental maladies). But insomnia is increasingly recognized as a profoundly impairing disorder in it’s own right. I’m hopeful that more and more people will recover as patients, physicians, and therapists give insomnia the attention it deserves!

How is insomnia diagnosed?

Insomnia is characterized by four main criteria laid out in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd Edition. In short, people with insomnia have:

- Trouble falling asleep or staying asleep.

- Daytime symptoms such as sleepiness, fatigue, or irritability.

- Adequate opportunities and circumstances for sleep. (In other words, you can’t sleep well even though you have a safe, quiet place to sleep, enough time to sleep, and you’re trying your best to sleep.)

- Crappy sleep at least 3 times each week.

When making the diagnosis, doctors also consider other alternatives that could be contributing to poor sleep. This can generally be done through an interview and physical exam, but some cases may require basic laboratory tests. A sleep study is rarely needed, although it can be helpful if the clinician wants to rule out obstructive sleep apnea or another sleep disorder.

Finally, doctors categorize insomnia as chronic if it lasts for more than 3 months, and short-term if it has occurred for less than three months.

What’s going on in the brains of people with insomnia?

There are several different models of insomnia, but the most compelling explanation suggests that insomnia is a disorder of hyperarousal.

To understand what that means, it helps to discuss some of the basic physiology of sleep.

Many people think that sleep is merely the absence of wakefulness—just like darkness is the absence of light. You might have pictured wakefulness like a dimmer switch: you become more alert when you turn it up, and you fall asleep when you turn it down. On the surface, this doesn’t sound like a bad model, but it doesn’t explain how your body actually works.

Scientific models describe sleep and wakefulness as opposing, active processes. Sleep is not passive; it is a vital physiological process that helps us save energy, create memories, grow stronger bodies, and flush out brain toxins.

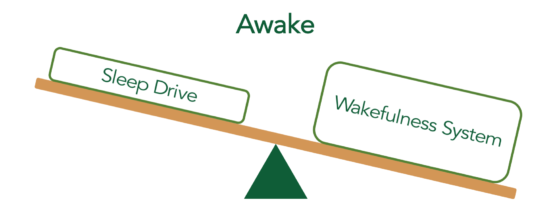

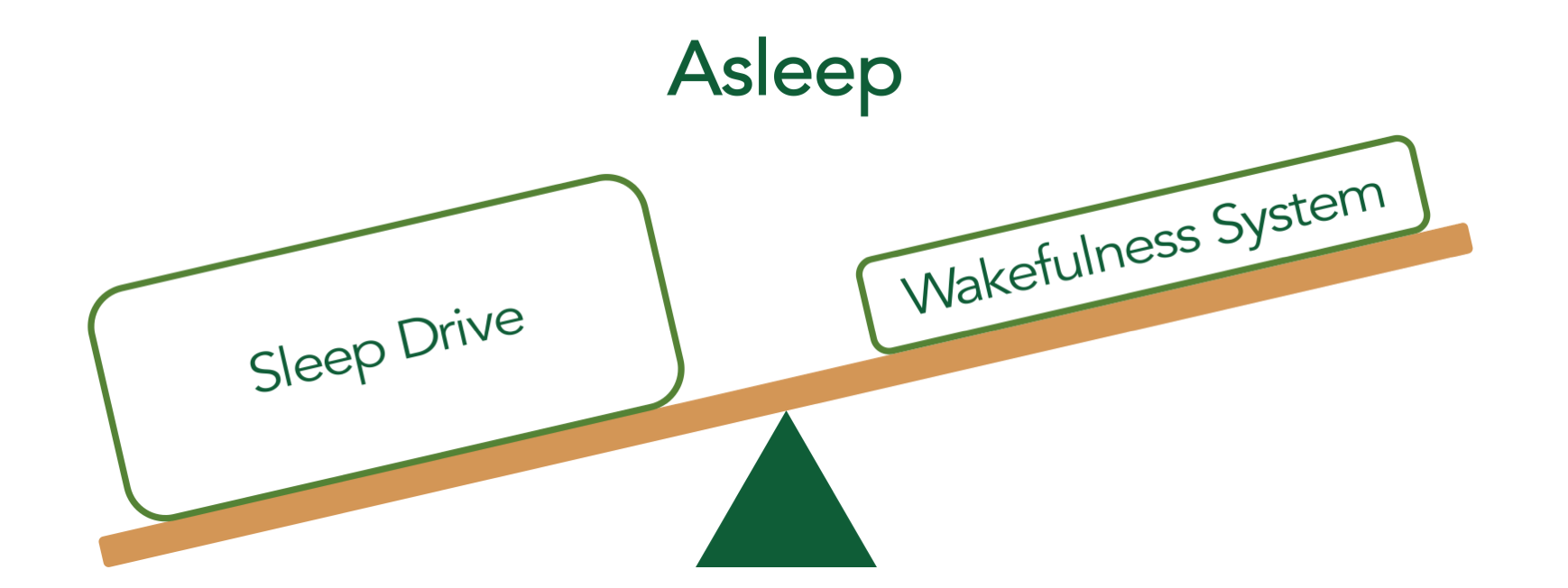

So when you think about sleep and wakefulness, it helps to imagine these processes on opposite ends of a seesaw. When your wakefulness system is more active than your sleep drive, you stay awake.

In like manner, sleep happens when your sleep drive becomes significantly more active than your wakefulness system.

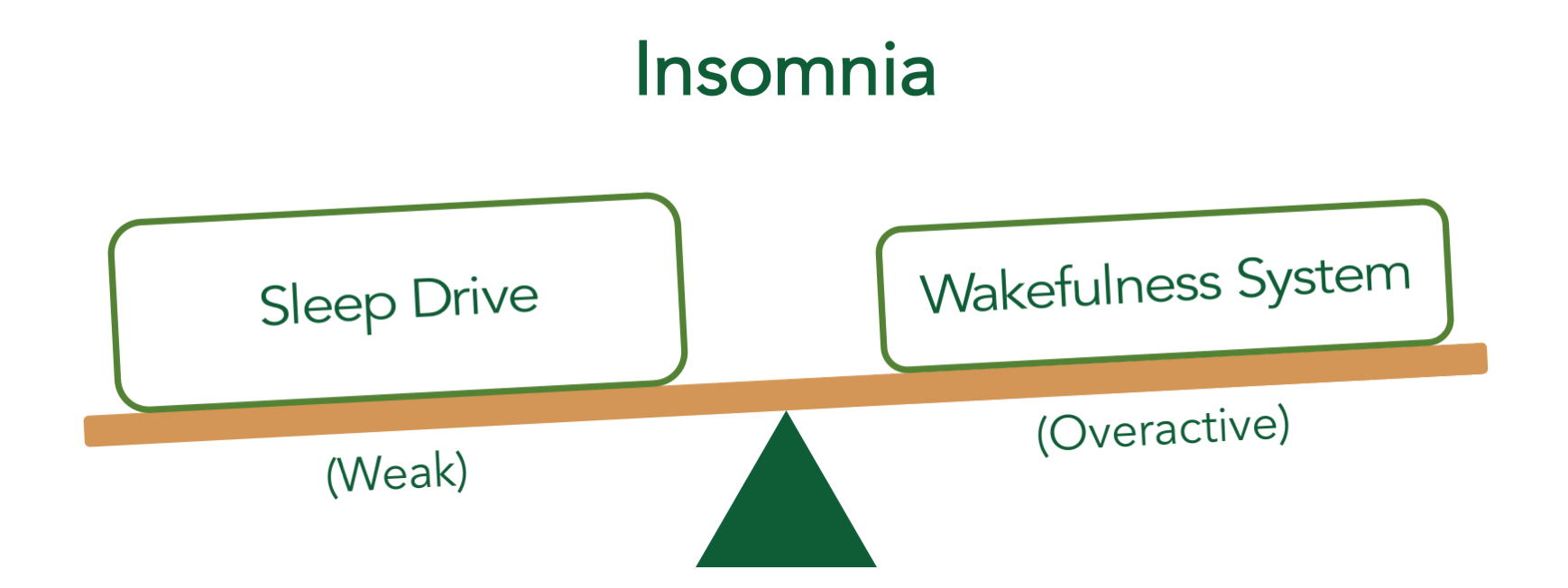

(Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of these diagrams—these seesaws represent a well-established model of sleep. Academic papers call this the “flip-flop switch model,” and these diagrams usually include a large number of obscure abbreviations and multiple kinds of arrows. This oversimplified should give you a sense of how this works)

This seesaw suggests two possible causes of insomnia: an overactive wakefulness system and a weak sleep drive. Experimental evidence supports both mechanisms, but an overactive wakefulness system—a phenomenon known as hyperarousal—turns out to be the primary driver of insomnia.

How is chronic insomnia treated?

When I was in medical school, I was taught that chronic insomnia should be treated in a stepwise fashion; I’d first address sleep hygiene, and then prescribe sedating medications when sleep didn’t improve. Unfortunately, sleep hygiene education is often not enough to significantly improve insomnia conditions, and so most patients who follow this approach end up taking sleep medications.

Current scientific evidence suggests an alternative strategy, and it starts with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I is a brief, behavioral intervention designed to reverse hyperarousal by maximizing the client’s sleep drive and turning down their wakefulness. It’s a profoundly effective treatment, and as many as 4 out of 5 people experience dramatic improvement after only 6 sessions with a competent therapist. Studies also suggest that motivated patients can recover by strictly following one of the many do-it-yourself curricula found online.

In head-to-head studies, CBT-I is at least as effective as medications, has fewer side effects, and continues to provide benefits long after therapy stops. For all of these reasons, CBT-I is now recommended as the first line treatment for insomnia by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Physicians, and the European Sleep Research Society.

(And in case you were wondering, CBT-I has almost nothing in common with other forms of CBT. If you’re still sleeping poorly after any other kind of therapy, CBT-I may still provide massive benefits!)

If insomnia doesn’t improve with CBT-I, most recommendations suggest that doctors collaborate with their patients to identify an effective medication regimen that enhances sleep. Ideally, these medications would be taken in small doses, and only as often as needed to promote sleep. However, a small percentage of people are unable to sleep well without medications. Adaptations are needed to make this work.

How is short-term insomnia treated?

Most research and treatment recommendations focus on chronic insomnia, since many practitioners consider short-term insomnia a normal–albeit painful–response to stress. In general, I collaborate with patients to determine the underlying causes of distress, problem solve around those areas, and (when appropriate) provide a very short course of hypnotic medications to help them survive the stressful period. Other clinicians proceed in a different way.

Is there any hope that my insomnia will improve?

Absolutely! The vast majority of people with insomnia experience significant improvements when they receive appropriate treatment. And even when insomnia symptoms are difficult to manage, there are many ways to experience a fulfilling, meaningful life in the midst of challenges. Don’t give up!

—-

Jeff Clark, MD, is a resident psychiatrist at the University of Washington and the creator of SlumberCamp.co, an online course that teaches the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). The images and portions of the text in this article were derived from the Slumber Camp curriculum.

No Comments