Episode notes:

No show notes for this episode.

Episode Transcript:

Paul: Welcome to episode 90 with my guest Jamie Franzo. I’m Paul Gilmartin, this is The Mental Illness Happy Hour, an hour of honesty—actually now about an hour or two of honesty. Ninety minutes, let’s call it 90 minutes of honesty, hopefully honesty. Oh my God, I’m in a fucking cesspool right out of the gate. Ninety minutes of honesty about all of the battles in our heads. From medically diagnosed conditions to everyday compulsive, negative thinking. This show is not meant to be a substitute for professional mental counseling. It’s not a doctor’s office. It’s more like a waiting—oh God, here’s another pit of quicksand—I have quite figured out how to describe this—it’s more like a waiting room that—I haven’t written anything down, I’m just gonna try to off the top of my head describe the waiting room—it’s more like waiting room that has magazines that are sometimes informative, sometimes titillating, sometimes sad—I don’t know what kind of magazine that would be—uh, PlayRefugee? Look at the way they’re holding that soup – that is sexy. Now I forgot where I am. What do I say after that? More like a waiting room that, uh—the website for this show—I’m back on track. The website for this show is mentalpod.com. It’s also the Twitter name you can follow me at.

Um, please visit the website, all kinds of good stuff there: a forum, you can post in the forum, there’s about a half dozen surveys you can take that help me get to know you; you can also see how people take the surveys, very fascinating. And I’m gonna be reading a bunch of surveys at the end of this episode today. Because I figured the people that don’t like the longer episodes, if I just kind of backload—if I’m gonna do a lot of surveys, if I just kind of backload them to the end of the episode, then they can just turn it off whenever they like and everybody wins, everybody goes home happy, everybody gets ice cream.

The winner for this week’s cutting board is Sarah Colletta Heald. The number I picked was 29 and she was the closest guess to it, she guessed 33. So I’ll be shipping you that cutting board in the next week or so.

And I went to the lumber supply place to get more wood and glue and I was like, “Motherfucker, I spent almost as much money on wood and glue as I take in in a month from monthly donors.” So I’m either gonna have to give away less cutting boards or I’m gonna also have to start selling, um, some cutting boards. Which I think I might do because I got some really nice emails from people that said that they would like to buy one if I sold them. So follow me on Twitter, and if I’m gonna sell stuff, if I’m gonna make like a cutting board and sell it, I’m not sure if I’d do it through Etsy or eBay. But follow me on Twitter and I’ll let you know. You can also check in at the website and I’ll post something there. I’m guessing I would probably—and this is filling me with anxiety to put this number out there because it’s expensive for a cutting board but it’s what it would be worth for my time to make one, $300 for a cutting board. Anxiety! That just gave me like—just—I can just picture like 500 people going, “$300 for a cutting board! God is he full of himself!” Talking through it. I’m talking through it.

A listener sent me—oh I almost forgot I wanted to plug my friend’s site, my friend Pete Schwaba has a new site. A lot of men are kind of clueless when it comes to shopping for women and don’t know where to begin and my friend Pete Schwaba has just launched a site that helps men shop for their women. And it’s called shopforyourgirl.com. That’s the address shopforyourgirl.com. So go check it out. There’s a lot more actually to the site than just a place to get ideas for shopping. You can actually buy the products there too as well, I believe. That would have been a good thing to know about your friend’s site, Paul. Before you fucking launched into a plug for it. It’s alright, it’s free. Pete if you don’t like it, go fuck yourself. There we go. I don’t think I’ve “go fucked yourself” a friend.

Oh, speaking of go fuck yourself, a listener Rosalie is making embroidered wall hoops of things that have been said on the show. And she’s got an Etsy shop and the two that she has up right now is an embroidered hoop of “go fuck yourself” and an embroidered hoop of “crying is just your soul blowing a load.” So I said, “Rosalie, I think you’re going to sell a lot of those.” And she has agreed to throw my free ones my way which I can give as prizes to monthly donors. Have I told you monthly donors how much I love you, how much you mean to me? Really, really means a lot to me.

I want to read a couple of excerpts—a listener—and I’m sorry I forgot who the listener was who sent me the link to this article written by Rhona Finkel The title of the article is Mental Illness is More Malignant than Melanoma. And I just want to read you some of the facts about—(dogs bark) apparently my dogs disagree. Hold on. I gotta pause. This is the part where editing is ok.

Much better, much quieter. This article—I just want to read you a couple of excerpts from it. “Mental illness and addiction steal more years of life than cancer and infectious disease but a provincial study by a McMaster researcher finds few of those patients get the help they need.

‘“The bottom line is that when you talk about burden of disease for mental health and addictions, it’s higher than virtually everything else,’” said Dr. John Cairney coauthor of the report and associate professor of family medicine, psychiatry and behavioural neurosciences at McMaster University. “When you look at the budget, much less money is allocated to mental health than it is to other disease conditions. That has been the case for some time.”

“The number of years of life lost is 1.5 times that of cancer and more than seven times that of infectious disease, according to the study published Wednesday by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and Public Health Ontario (PHO).”

“The five conditions with the highest burden are: depression, bipolar disorder, alcohol use disorders, social phobia and schizophrenia.

“Depression is the most burdensome condition — worse than lung, colorectal, breast and prostate cancers put together.

“Alcohol use disorders contributed to 88 per cent of the total number of deaths attributed to these conditions.”

So there you have it. Enjoy. Go masturbate.

I think I’m gonna wrap up the intro with some love. I can never get enough love. This was sent to me by a listener who calls—I don’t know if this person’s name is Savannah or not. If I remember correctly, I think Savannah is a transgender person and I just want to read some of Savannah’s loves. “I love my nine-year-old cousin’s gapped teeth.

“I love waking up in the morning and immediately falling back to sleep.

“I love the first few seconds of all my favorite songs.

“I love the awkward exaggeration on a stranger’s face when they can’t tell if I’m a male or female.

“I love laughing with my coworkers at work.

“I love a fresh sack of weed.

“I love listening to a song enough times to memorize each word by heart.

“I love spending cash money after just getting paid.

“I love the crispness of a new dollar bill or the shine of a new coin.

“I love junk food in the middle of the night.” Oh yeah. Oh my God, the number of times I’ve just pounded cookies at three in the morning.

“I love riding my bike in the middle of the street when there are no cars out.

“I love my grandma’s ability to love me and understand any issue I am dealing with.

“I love my friends back home telling me they miss me and asking when I’ll go for a visit.

“I love the memories I make each summer and knowing there are many more to come.

“I love finally living in a city where I can comfortably spread my wings.

“I love TV marathons of my favorite shows.

“I love wearing pajamas all day.” Oh I fucking love that one.

“I love snow in my home town.

“I love writing or drawing something and realizing I still have potential.”

[SHOW INTRO]

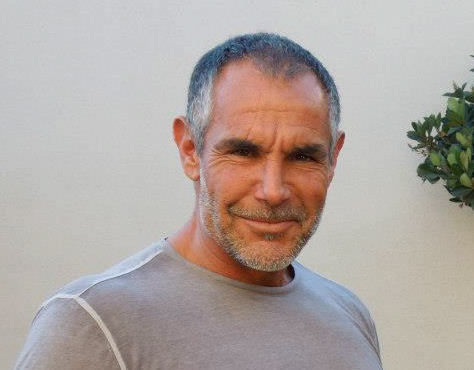

Paul: I’m here with my buddy Jamie Franzo, who I’ve known for how many years, about six years? Something like that?

Jamie: More like eight.

Paul: Eight? You’re one of my favorite people in the universe. When you walk into a room I feel better. I just—you’re just one of those people that I’ve just always felt a connection to. I’ll describe Jamie to you physically. He’s about 6’3”.

Jamie: I used to be about 6’2” I’m about 6’1.5” after multiple surgeries.

Paul: You seem like you’re 6’3”. He used to be a K1 kick boxer. He works out. He’s got a scar running from his forehead down to his chin and he’s got tattoos, almost no body fat. And he has worked security for a number of years. If somebody said to me, “You’re gonna be attacked and you can pick three people to be on your side,” I would say, “Jamie, Jamie and Jamie.” I just feel safer when you’re around. Not that I’m afraid people are gonna attack me but there’s something great about having a badass be your buddy.

Jamie: What a solid thing to say. Thank you.

Paul: Jamie makes his living doing voiceover work, sometimes doing security, but more importantly he is a sober guy that used to enjoy putting heroin into his body.

Jamie: Yeah.

Paul: How many times do you think you’ve shot up?

Jamie: Oh wow. Well I was a junkie for more than a decade and so let’s see that’s 3600 days and sometimes you have to fix 8 or 10 times just to say well.

Paul: So more than a dozen.

Jamie: Safely, safely said yeah.

Paul: How are your arms not all fucked up?

Jamie: I have some, two or three, they look like cigarette burns on the inside of my arms, from abscesses or infections from the tip of the needle being infected with some bacteria. I’m lucky not to have caught anything more serious than that like Hep-C. I was just speaking to a friend of mine who’s undergoing interferon treatment for the third time and it’s just hellish. Usually antibiotic will kill the infection that comes from the abscess.

Paul: All junkies need a mom that runs in and hands out Handi-Wipes before they shoot up.

Jamie: Yeah. That’s—don’t want her around at that point.

Paul: Mom, can you meet me at the shooting gallery? I think some of the needles there are dirty.

Jamie: With some alcohol swabs.

Paul: Yeah. What—we’ll get into the early stuff in your life, but just give me a snapshot of the lowest low of your using. I’m sure there were many.

Jamie: Yeah there’s many. Most recently, this was, well we knew each other, so, and I had had a little over a year clean and sober and then I relapsed, chose to use, people like to say slipped or—I wasn’t maintaining what I know is what keeps me sober and went out and within five or six weeks I was guarding the entryway of a two man tent on Gladys and 7th, which is a block from Skid Row downtown LA for a gentleman with one leg in his 70’s named Rabbit who got the best heroin delivered to him by some, I won’t mention the name of the Mexican gang, that would deliver him his bundles in the morning of heroin balloons that he would sell from the tent doorway and I would be just ten feet away against a chain link fence making sure that he was—his business was running smoothly and no one was trying to rob him. And then every few hours he would give what I needed to get through the next few hours. And I was sleeping next to that, for lack of a better way to explain it, creature, noisy creature each night. You don’t get much sleep down there in that neighborhood, but… And I was really happy, that was bliss, not having to work or do my, you know, normal hustle other than keep an eye out on him. He was an interesting character. Like most junkies, very sensitive, you know, wonderful story. He was never boring. But that was a pretty low time. More than a number of times in the six or eight weeks that I was down there—

Paul: I hear that story and I say you can be a junkie and still hold down a job.

Jamie: Yes. Yes. And live at your work. But—no, but I ran into a number of people talk about shame, embarrassment, there’s really not a word in our language for it when you—someone you’ve worked with, you know, is coming down to score a little crack or heroin and you both give each other that look, you know, and it’s pretty bad. You’d be surprised. You’d be surprised. I don’t know if you’d be surprised – you’ve kind of seen it all with me. But yeah.

Paul: We really thought you were gonna die, we really did. And it was that classic thing where it doesn’t matter how many people love you, when you decide that you want to go numb, you decide you want to go numb. And we knew to not take it personally, we were just praying that you got tired of it before you died and thank God you did.

Jamie: Well I remember during that particular time I’d gotten tired of a number of things, and anybody that I knew from my family to some of the men I got very close to in our fellowship, my girlfriend at the time, not really a girlfriend, just a relationship of convenience, it was an interesting time because I had grown absolutely tired of the attempt to manipulate anything or anyone anymore. I had given up.

Paul: It’s a lot of work staying high.

Jamie: Yeah, yeah, and it wasn’t that I ran out of, you know, a couch to crash on or a $20 bill I could borrow from somebody, I just didn’t have the whatever it took to ask anymore. And yeah your hustle, it—you start to lose it. You start to lose the—people refer to it as the will to live, I mean there was—unconsciously for me, I mean I wanted to survive, I desperately wanted to live, I just didn’t know how. I just didn’t know how. I remember looking at people that, all throughout my addiction, looking at people early in the morning, when I’m still out, you know, getting ready, you know, they’ve shaved and they’ve bathed and they’ve eaten and they’ve—they’re getting into their car with their briefcase and I would think, “Sucker.” You know, what kind of life is that. And then thinking how, later on, how it’s beautiful when I’ve seen people—when I hear the hustle and bustle in the morning. I was sitting on my balcony this morning and I’m up early, I’m up, you know, 5:15-5:30, it’s dark still, having coffee on the balcony, and I don’t know—today, I’m anxious to greet what’s coming when I wake up in the morning. That’s such a far cry from the way it used to be.

Paul: Let’s go back to the beginning and talk about maybe some of the stuff that made you want to get high. Who knows? I mean maybe genetically you and I were just born to get fucked up no matter how good our lives were. Almost any addict or alcoholic or any person that does something super compulsively to numb out, there’s something from their past usually that, if not is the reason, is certainly gasoline on the fire for that.

You were born in Brooklyn and then you moved to San Francisco?

Jamie: Yeah, very early on my family moved to, I was two, moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. My dad got a job, did foundation work for large construction companies. He got a job doing the foundation for the Federal Building in San Francisco. So that was a big opportunity, big promotion for him. And we—he actually moved us to San Mateo, about fifteen miles south of there to a hotel called the Casa Mateo and I think it was $9 a night back in ’64. Wasn’t a bad place. Wasn’t the best place I’ve stayed but it was sweet.

Paul: It was no rabbit tent.

Jamie: No, absolutely not. No I come from a very loving home. I never wanted for anything. I certainly had love and nurturing and my parents just recently celebrated 60 years of marriage last year. They uh—it’s um—and I’ve heard this from so many sources that I think it’s the consensus that it’s a joy to be around them. They, um, they love each other warmly and thoroughly and out loud. You know, the boisterous Italian, really thick Brooklyn accent still, both of them, many, many years out of the heart of Bensonhurst, but you wouldn’t know it. And, yeah, so that’s where I was born.

Paul: And your dad is definitely an alpha male.

Jamie: Yeah my dad is that. My dad—I was just thinking of his hands when we were talking. He’s got a layer of callus—he’s in his 80’s now, early 80’s and he’s got a layer of callus from construction work. Just hard work, he’s just a hard working guy. I mean, he never cheated on his taxes. I’ve never caught my dad embellishing the truth, let alone telling a lie. He—interesting guy. Disciplinarian. So as far as the connecting it to, later on, the addiction, I think my first addiction, I used to say it was food because I was a very fat kid. Today they refer to it as clinically obese. To give you a visual, I was 250 pounds at 13 with at 55” waist. So I could only wear bib overalls with the buttons undone, rolled up, adult as a 13 year old.

Paul: To be fair, you were 16 feet tall though.

Jamie: No, I was not 16 feet tall. No I have—I used to say my first addiction was food, the first I remember, but looking back now I think my first addiction was attention, any kind of attention. And I got a lot in my home. I had an older brother and I had a grandmother that lived in the house, you know, who told me I was the best boy, the smartest boy, and the most handsome boy. And I loved that. And …

Paul: Was it just you and your brother?

Jamie: Uh huh. Uh huh. And then at—when I was 13-and-a-half, my brother was on a full ride scholarship to play football at Cal Berkeley and he also was a straight A student, the polar opposite of me in this—character-wise in the sense that he was quiet, introspective, and he got in a motorcycle wreck and three days later passed after a couple of surgeries on his brain to relieve the swelling. He had a bad, bad head injury and months before that I had endured a trauma that, you know about this, we’ve talked about it at length, and what I’ve come to learn about that particular trauma is it’s really not close to the worst of what I’ve experienced with people I’ve been in treatment with for post-traumatic stress. And I’ve also learned that trauma is relative. Mine was the, I think, the first time that I can identify when I chose to begin to play a victim, when I chose to separate myself from, certainly my peers, but the human race, as someone who has gone through more pain and darkness.

Paul: Jamie, how could you not, do you mind recounting?

Jamie: I don’t mind, I’m just gonna kind of glaze over it, share in a general way. I was walking a dog from my—from a family friend, a black lab named Benji. Like I said, I was awkward, I was fat, I wore horn-rimmed glasses with tape in the center because they would break a lot. I was restricted to what I could wear. I was a goofy kid – loud, and I didn’t have a lot of friends, so Benji—Benjamin was the dog’s name—Benji was my friend, my confidante. I loved this dog. It’s tough to—I know there’s some of audience out there that understands the love of an animal, but because I didn’t have much else in my family, this dog was just—there was something that we had a very unique relationship. This dog seemed to have known I was coming, because he was excited to see me. To this day I wish people could greet as enthusiastically as that dog would greet when I would come to pick him up. And that was five days a week, I’d walk him for an hour or two, and sometimes it would be four or five before it got dark. I always lost track of time. We’d go to San Francisco Central Park and San Francisco Central Park is beautiful and very large. It’s big and spread out and there are areas—there was an area they were building, it was a sunken atrium that had tiers and it was under construction, and there was a group of—I won’t name the bike gang because I just won’t name the bike gang. Pretty, uh, pretty rough characters. And they were—come later to find out they were on angel dust or PCP, which is a hallucinogen, and they—but the dog got off the leash and went into their group and they hurt it pretty bad, and I heard him yelp and came back to me with a limp and really at that point I just saw red.

And I got the dog home, which was only a few blocks away and I came back. And they were maybe a football field’s distance from where the bike gang was hanging out, their motorcycles were parked. And I say “motorcycles” roughly, these were like a ragtag group of, you know, pieces and parts, but, you know, to that kind of a character, that’s their pride and joy, that’s their prize possession, and I had snatched a bottle of lighter fluid from the barbecue on my way out, and a couple of strike a surface matches and poured the contents of it on the bikes and lit the bikes on fire.

Paul: They were at the bar at this point or something?

Jamie: No, no, they were right in that atrium area that was being built in Central Park about 100 yards from the street where the bikes were. And I was standing by the bikes. I backed up to get out, you know, from the heat of the flames, but then what happened was the gas tanks at different degrees of full or empty were blowing up like the 4th of July. Explosions – loud explosions. And they all stood up and turned around and I’m ten feet from the bikes celebrating. And, you know, it wasn’t too hard to connect me with the dog that they had hurt, and so I ran across the street, and by the time they got up I was around the next corner and hiding out. But someone must have saw where I was—where I went and hours later they grabbed me in a Ford van, an Econoline van. And they took me to their campsite, which—kind of their hideout about 30 miles away in the Sequoia mountains and it was a known hangout for these guys. On the way out there, in the back of this van, I was tied up, I think I was—my hands were tied with a ripped t-shirt and they stuck a rubber ball in my mouth and I had kicked the back swinging door open, and a woman saw that there was—what she reported was a young woman being abducted and got the license plate number. Now three days later, they trace the license plate of the van to the father of one of the girls who was known to date—have a boyfriend that was in this bike gang. So that was kind of miraculous when I found out later. But in that three days, bound to a tree, some unspeakable things were done to my body, lots of stitches, lots of broken bones, attempts to—now these were drug-induced hysterical kind of lawless characters that were challenging each other to do certain things. And, you know, looking back, I played a part in it, because I was certainly challenging them as well. “Get me out of here, get me off this tree, my brother’s gonna come for you, my, you know, family’s gonna come for you. I’m never gonna forget your face.”

Paul: We’re you afraid they were gonna kill you?

Jamie: First of all, if I was, I wasn’t recognize—it didn’t silence me. It didn’t calm me. I was petrified, I mean I was—I today connect fear with paralyzation, with—fear with being unable to move—crippled. And I didn’t shut up for the first 24 hours. I think I was—I was able to call them back. I remember this, unfortunately like it was yesterday. And you learn a lot in 72 hours bound to a tree about human nature. You learn a lot about—there were characters that I could talk back, by appealing to their emotions. “You don’t want to do this,” you know. “I have a family. I’m 13. You know, this is horrible, please.” And then that doesn’t work with certain characters so you go at their ego, I mean I’m able to connect those dots today.

Paul: Wow.

Jamie: And, you know, I can remember the first night, how horrifying the leaves cracking, dry leaves cracking, because some of them passed out and some of them left the campsite. And I can remember not knowing if it was a wild animal, because there are mountain lions, there are bears in the California Sequoias. Badgers, who knows what it was? I can remember how petrified I was and then the change a night later, I’m now hungry. I’ve called my voice out. There’s nothing audibly that will come out. I’m struggling to breathe because of the damage done to my ribs and my sternum and my jaw and my neck. And my eyes are swollen shut with blood dried in them. And one of my nostrils is closed because the blood dried in it. And big change—you hear the crackling of the leaves and it’s not what you’re afraid of anymore.

So I remember I was alone on the third morning and it was dawn and the warmth of the sun coming through the trees felt good on my skin. I hadn’t lost hope and I heard my name. And I heard my name not be a familiar voice, I heard my name by a stranger. My first and last name. And the next thing I knew there was—it seemed like that was way off in the distance, and it seemed like seconds later there was someone unbounding me from the tree. And it was what I later found out was a ranger, a forest ranger from the particular closest park around there. (sighs) And then I was—

Paul: What are you feeling right now?

Jamie: (sighs) You and I have talked about this before. I have talked about this a number of times in session with a therapist, in sharing with other friends of mine that are similar survivors of trauma, and on my way here 30 minutes ago, I was telling myself—I was giving myself parameters of how deep I was going to go, and I wasn’t planning to go that deep. And I’m comfortable with this. I don’t feel uncomfortable. I feel like—I feel a level of healing that I’ve never experienced before because I almost feel like I’m telling you about something that I witnessed rather than something that I endured. Because gone are the feelings of—that’s what I feel—kind of a fullness in my acceptance, but really my body was abused, but they couldn’t touch the best parts of me. Nor can anybody on this day touch the best parts of me. That’s something that you volunteer. That’s, I think, the beauty in the truth that was shared to me with other victims. And I only use that as a word, in the vernacular that you have a perpetrator and a victim. The damage that is done, the permanent damage that’s done, it really is your choice in what you allow to be permanently damaged. And what I realize is that I—how many times my story, this story has actually helped another human being in really just letting them know they’re not alone. Although a totally different set of circumstances in the trauma, that the confusion and the swirling, cuz this is unnatural, what happened to me, as far as my scope of what’s natural. So what do I feel? I feel grateful. I feel—I remember what I felt when I heard my name.

Paul: What did you feel?

Jamie: I felt like, “I’m saved. I’m going home.” I felt something like that in our fellowship early on too. You know. So how ‘bout those 49ers?

Paul: The feeling, obviously I’ve never experienced anything even close to that, but I have experienced what you talk about when I realize that there is hope and my life isn’t lost and that other people are there for me and recognize what I’m feeling and experiencing. That feeling of being rescued is amazing but to get to that place, you have to say, “Please help me.” That’s so hard if you haven’t been taught how to do that our you didn’t have role models that asked for help.

Jamie: It’s really powerful what you just said. I find myself—I’ve become hypersensitive of late—I’m restudying with my mate, my girlfriend, in the morning, the study book for The Power of Now. And recognizing my thoughts and recognizing my mind and the negative self-talk, really. And the truth that I’m not my mind. And you’d be surprised how many times that I say in the course of a day, “I don’t have the answers, I need Your help.” And I’m speaking now to my Higher Power. Two hours ago my girl and I—I was saying before this interview, you know, we’re moving, she has incredible stresses at work, and this has been an ongoing thing. We’re—I have my set of things that are causing me stress right now and we’ve been going through a tough time. The good news is we stick out tough times. We’ve had a number of them and we know we’re in a downswing right now but we’re sticking it out. And I was saying goodbye to her, to get myself together to come see you, and—which was an awkward, uncomfortable moment, and I was—she stopped the car, she said, “Honey, come back to the car.” I came back to the car, I went back to the car, and I really wanted to make her pay for my emotional state, the frustrations that I’ve had today. And I see that face, and I see those eyes, and I’m looking at her, and I said that to my God, I said, “Please, I don’t have the answers here. And I need your help.” Because I want to be loving and when I go to bed, that reservoir—I reach in and there’s nothing there presently because I’m, you know—and it’s no longer ok for me to have that excuse but it’s been shown to me and it’s been my practice and my experience that it’s ok to ask for help. And in that moment I got what I needed. And I think that I was facilitated with this big smile that came across her face. Because just in the few seconds that I didn’t make her in any way pay for my emotional state, make her responsible for my emotional state, she found whatever it took, her smile made me laugh, really at myself, because, I mean I have so much to be grateful for. An incredible forgetter, you know, her smile, my laugh, the next thing you know I’m going around the other side of the car to put this—half of this large body in her front window so I can squeeze her and give her a kiss properly goodbye and really save the day.

Paul: You touched on something that I think is so central to anybody that enjoys this podcast and gets something out of it, and that ties us all together – is that in that moment you felt overwhelmed, emotionally overwhelmed, and your first instinct is to go to that first tool that we learned when we were kids or teens or even babies, to just lash out, to let that steam out. Because there is a certain primitive kind of release in lashing out, but it’s so unmanageable because it creates so much wreckage, because then the other person’s on the defensive and then we can’t connect with them, and this person we’re sharing our lives with is in one corner and we’re in the other corner, and we’ve turned it into “I win, you lose.” You know, how much sense does that make with somebody you’re trying to build a life with? That you are going to have sex with at some point in the future, that you are thinking of yourself as a victor and them as a vanquished. And it’s—for so many years that was my mentality, was—it was about being right and winning. And it just eats at the foundation of a relationship to come at it from that point of view. But when you don’t have any other tools and you feel overwhelmed and you are sensitive, you know, hypersensitive person, you don’t know what else to do. Because it’s so overwhelming when you feel cornered or you’re so full of fear about the rest of your life, and them leaving the dishwasher door open is the final straw. You know, or something ridiculous.

Jamie: Last night when we talked briefly and you had asked me about my fear list, my biggest fear, when I’m in the overwhelming moment, is that—and it’s my smallest fear, a fear that affects all the areas of my life. I used to playfully say it’s the—under the heading, “Don’t you know who the hell I think I am?” So in other words, a false sense of myself. But it’s the fear of not being recognized. It’s the fear of not being—having the proper amount of praise in a given moment, you know. Had a long discussion with a dear friend of mine who is on the downslope of celebrity status and where we were relating, I was in the nightclub business. I was in and around it for 25, nearly 30 years, from San Francisco nightclub door jobs and New York door jobs to parlaying all of that into a nightclub partnership in South Beach Miami in the early ‘90’s. And the position, the power that it garnered me, this celebrity if you will, this microcosm of South Beach Miami and the nightclub world, to be the partner in the spot for four or five years. You’re basically God king of your world. So you have to recover from that when that fades into darkness.

Paul: Especially if you’ve made that who you are. In your mind that’s—this is the most important thing about me. If you decide to let that be the most important thing about you at that time.

Jamie: I think that—because I’ve put a lot of energy into trying to figure this out. I can’t really can’t really come up with a time or a period of—or a timeframe where I made a conscious choice to be that guy. I can say that when you’re working the door of a place and you’ve earned the trust of the owners and they say, “Hey, this season we’re gonna go out of town a lot more because our primary home is New York, we might like to make you a partner, and your ten percent in six months becomes fifteen and then twenty-five,” and then they’re interested in doing a place with you, and now you have this place where you’re full partners, incredibly successful. I won’t take any credit for that. It was all timing. We had a formula that had worked other places but it was really South Beach was exploding, and you could open a hot dog stand and do very well. It was like riding a wave. So—and there was a seduction in the “Oh, your money’s no good over here.” Table and bottle service and things on the house other places that you go. Jet ski rentals on the beach, whatever. It’s because you’re this person, everybody wants to say they know you. There’s a—I don’t know what choices you make to become that guy. I enjoyed it, I worked it. My—the depths of my disease and my addiction, my heroin addiction, my cocaine addiction is what snatched that opportunity from me, is what burnt it to the ground. I burnt the trust down to the ground with those two partners that were like family to me. My partner’s wife was like my second mom. It’s not the way you want to go out, with your tail between your legs. So—and I’ve, uh—like when you asked me what I was feeling, when we were talking about something that happened to me in my early teens, I have a similar perspective to how long it took me to recover from being nightclub guy, know. Because I’m truly learning to appreciate just being a guy in a room. We like to affectionately say a worker among workers. There’s so much less pressure, so much less expected of you, so much less responsibility. It’s exhausting to be who they think you are.

Paul: It’s oppressive, yeah.

Jamie: you know. And it’s fascinating to me, we were touching on some things earlier and I was thinking my father, he lost my brother—my father has a son today. My mother has a son today. My girlfriend has a mate that’s constantly looking at ways to honor the relationship. My friendships with men, and I count you among them, we’re there for each other. I have relationships today—so I had this relationship with an image of myself that took thousands to fill, and now with a handful of intimate relationships that are based on truth and being a safe place for each other there’s—I mean I’m fuller, I’m talking behind my sternum here, my chest, than I have ever been. I didn’t now this was possible.

Paul: Isn’t that trip? The ego needs a fucking Roman banquet every four hours to stay sated, and our soul can nibble on a crouton and be like, “This is the fucking tastiest crouton in the world.” But it’s so hard because we live in a society that is ego-driven, that tells you success are all of these things that are attached to your ego, and it is so hard to unlearn to them, it is so hard.

Jamie: In that decade that I was trying to stay well and running from everything that fed my soul, I left—

Paul: Staying well is a term that heroin users use meaning you don’t even get high anymore, you just shoot up to not feel withdrawal. For those listeners that aren’t hip to that kind of lingo.

Jamie: I had walked out on my sons, three and six years old in my—coming up on five years of clean and sober time with a year and change before that, I’ve had them both back in my life. Building trust again and building a relationship for the better part of seven years. So we’re—we got a pretty good thing going, me and my boys. My oldest and I have really bonded this last month behind a number of circumstances, traumatic for him. The loss of a girlfriend, right before that, the loss of their child because of complications in her pregnancy, her moving out of town, and he called me the other day to get some information from me, get some direction, get some advice on somebody he’s newly enamored with. And to be a go to person for that 22-year-old young man, that my opinion number one, that he—it’s part of what he uses to make decisions, that he—and he said this directly to me and he’s shown me in many ways, that, “I need your perspective, I need your input here. Before I make this big decision I want to get your take on it.” Just a couple of words that we shared, I gave him my—I was checking in with something that he was going to attempt. It worked out well. In brief, he thought he made her feel uncomfortable, he was just gonna brush it under the rug and hope that it went away. I said, “I want you to call her. I want you to, you know, have a short conversation and make sure she understands, if you made her uncomfortable, that you didn’t mean to. Just clean it up.” And it went real well, and we got off the phone and I saw his face in my mind’s eye and I thought to myself, “I’m the richest man in the world to have the opportunity to have a meaning and a purpose in this young man’s life, who happens to be my son.” And it’s rare that that’s not attached to, unhealthily on my part, attached to not feeling deserving of it.

Paul: Can you describe ten years ago when that son would have been 12 years old, what he thought of you?

Jamie: Well, we had—we’ve a number of conversations about that. It was horrifying to my son at times. He felt like he was alone in the world, you know?

Paul: I’ll never forget the night—you hadn’t seen your sons in how many years was it? You were newly sober at this point.

Jamie: I hadn’t actually seen them in nine and a half years.

Paul: Jamie and I and a group of other people, a support group that we go to, we eat dinner at this place next to where the support group is, and Jamie hadn’t seen his son.

Jamie: My youngest boy Chris.

Paul: In nine years. And Jamie and myself and a couple of other people are sitting down at this place, and your son walks in with his stepdad and mom to eat. Can you talk about that?

Jamie: Phew.

Paul: Pure coincidence.

Jamie: Their stepdad—mom actually was around the corner in the car, they were picking up food to go at a place we sit and eat at. And they had called it in, so they were walking in, walking towards the counter, and I recognized their stepdad who I’ve had some interesting encounters with in the past, and last of which was very ugly. And when I initially saw him, because of the last time I had seen him was many years earlier, it wasn’t good, I kind of bowed up, full of nerves, prepared for anything to go down, and taller than him, and right behind him was this large, baby-faced 14-year-old boy who looked like me when I was young. And I was darting back between the two of them, and Chris, my son, had a big smile on his face and saw that very soft, greeting for me, he said, “Hey, man, how are ya?” And I, you know, said the obligatory, “I’m Ok.” And he said, “Do you want to say hello to your boy?” And I said, “Hey Chris.” And he goes, “Hey.” And I said, “Let’s step outside.” And we went outside and I don’t remember what was said, but I remember how hard he was working to calm me down in a good way. He was excited to see me. And what took place over the next ten minutes, he—at one point I was, you know, I was babbling, I didn’t know where they lived, I couldn’t find them. I was court-ordered to stay away from them, that court order had lapsed, but I hadn’t done the proper—the necessary court protocols to be allowed to see my children, but I found out shortly after I was allowed to see them. I—he said, “Hey, Dad. Chill.” You know, he said, “I think there’s somebody that I’m gonna wanna call.” So he took my cellphone and he called my oldest son and he said, I remember it verbatim, he said, “You’re never gonna guess who I’m sitting her talking to.” And I could hear my oldest boy on the phone right there, it was very close to me where I could hear it, he said, “Jimmy?” And he said, “Yeah.” Because some of my friends, my old school friends refer to me as Jimmy, and he said, “Where are you guys?” And he said where we were, and he said, “Invite him to my football game Friday night.” As you know, our meeting is on a Thursday, and the next night I was at North Hollywood High School Huskies, Friday night lights, and my oldest boy was playing the position I played in high school football as a team captain. And I got to sit there and watch him. And we hung out for a couple of hours afterward. And that was the beginning of our long, arduous, very productive, painstaking, journey in putting back together something that I thought was forever shattered.

Paul: I hope anybody listening to this who thinks, “I’ve fucking blown it, you know, I’ve—all hope is lost,” I think our attitude about things probably snuffs out more hope than anything else and if we just keep taking the next right indicated loving, honest action, the universe has a really weird way of meeting us halfway.

Jamie: You know, I’ve probably heard that said and you actually say that combination of words in that sentence you just said a number of times, and I—it just gave me goose bumps that started in my chest and down over my shoulder blades. Yeah, I don’t want to take credit for any of this, I think that this universe that you talk to—talk about, refer to, I call God, and I’m at in so many areas of life, all areas of my life, but especially in my relationships with son as much from the grace of that power, as I am from—really the most powerful thing I’ve ever done, as we talked about earlier, ask another man for help. Ask for help. My first cry for help was to God, to the universe, just help me. It was brief. My prayers are consistent and they’re in the morning and they’ve expounded and expanded to more than just help me.

Paul: Me too. And that’s what saved me. Was July 21st, 2003, I was tired of wanting to die and I just said out loud, “God help me, I can’t do this anymore.” And my life changed. And I sometimes call it God too, but I also know there are people that listen to this podcast that the word God has been really, really tainted for them by bad experiences with either organized religion or somebody in a position of power that talked about God a lot that abused their trust. And so I probably edge away from it more than I should if I’m going to be really honest with myself, but I want this podcast—I hate the thought of somebody turning it off unnecessarily and so I don’t call it God as much as I should, even though I can’t wrap my head around the fact that there would be an entity with—that hears what I’m saying and consciously processes it, because it has to kind of work with science for me to get it, but I call it God, I call it God. I believe in God.

Jamie: For me personally, when I think of—not the exaggerated, not the printer, not the sculpture in a Catholic or any other church of Christ on a cross, but the actual man on the planet, for 32 years, and his—the example of his life, it’s a pretty good example of service. It’s a pretty good example of selflessness and sacrifice. And that is the example, I’m a follower of Christ. Because in this moment, in this day, my top three things that I’m trying to be more of is: gentle, kind, and selfless. So that’s still a pretty good example for me. Now, it’s not anything that—and I believe this about God and faith that should separate from anything or anyone—I think it should be all-inclusive, you know. I have a totally different take on the structure, you know, the pomp and circumstance of what I was raised in, that’s just become so much deeper and wider today. And I like it, I’m comfortable with it.

Paul: And I think the most important thing is the seeking. And we’ll never all the answers, and I’m always wary of any person, you know, who says, “I believe in God,” and then somebody says, “Then why does this happen?” and they have just pat answers for this. Why are they afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Somebody said one time, “If God was small enough for me to understand, God wouldn’t be big enough to solve my problems or give me comfort.” And I like to think of that. And I suppose sometimes I can be that person because maybe there’s an instinct in me that wants other people to know that there is this power in the universe that I tapped into to save my life, and there’s other people like you who have tapped into it and it saved your life, and we don’t know exactly how it works and operates and what form it takes, etc., etc., but we know there are places where we can show up and actions we can take where then we get that feeling, that it is there, and that feeling is so deep and so profound I feel it in my bones. It’s the deepest truth that I know. But you can’t make somebody else understand that. You can’t get them get there intellectually, and maybe that’s the gift of a bottom, is the intellect is forced to lay down. It’s spent and then your spirit is allowed for once to lead. Because I believe if the spirit doesn’t lead, the body and the mind whither and they want to die. I think the spirit has to lead – all our decisions have to be filtered through some type of a spiritual discipline otherwise I just think we become lost and scared, and we become scared regardless, but we become driven by, I believe, that fear, that becomes the, kind of the master that we serve. Because I think everybody—but Bob Dylan wrote a song, Everybody’s Gotta Worship Something and I believe it. I believe everybody has a God, they just don’t know it, might be being attractive, it might be being rich, you know, getting your dad’s approval, whatever, but I think the beauty in running your life off the rails and asking for help is you’re forced to really look at what your God has been and go, “Is this working for me? Is worshipping this thing working for me? Is worshipping heroin and being a Mr. Nightclub working for me?”

Jamie: Interesting, actually fascinating perspective that you just shared. I just—it was able to help me to connect some dots because I think what I worshipped was what I thought would be—because I had worked so hard at separating myself from the pack, and what I became was an animal. I became chaos. And that’s one thing you can count on with me consistently, in New York and Miami, that there’s no rules, you know, nothing is going to surprise you to hear that story the next day, and not having any boundaries was what I—that was my aspiration every day, to not have a game plan.

Paul: The great danger too—you know the ego has to separate us from our fellow. We’re either better than or we’re worse than. That’s the only—the ego cannot conceive of being one of many, that is just—the ego hates that. And when we’re living in ego, and we’re in self-pity because we think we’re worse than everybody or we’re in grandiosity because we think we’re better than other people, you’re bound to feel lonely. You know, for years I wanted to be a standup comedian apart from other standup comedians. And I couldn’t understand why I felt so lonely. Well my pursuit was to distance myself from everybody. And I didn’t even achieve what my ego wanted financially or professionally but I achieved it spiritually by separating myself from other people. And it didn’t occur to me until I’d been sober about six years, it was, “Oh my God, my fear is that I’m not special, that my life is forgettable.” If I can overcome that fear and be comfortable with being one of many, my life has a chance to take on meaning, and the odd thing is that one of the byproducts of that has been that I do get to feel special because I get to connect to people, but it’s a different kind of special. It’s not getting in TV Guide special, it’s laying my head on my pillow at night and feeling I have a purpose special. Which my ego does not care for.

Jamie: It’s interesting that you—you’re—this morning, again with my girl with that reading, another reading, she—there’s—I’m reminded often of why I’m with her and why I don’t ever want to lose her, is because she’s—she will say something I’ve heard before oftentimes but in a certain cadence, or a certain rhythm, or a certain—something connects for me when it’s coming out of her mouth and we were talking about the ego this morning and you touched on that. This ego that lives within me will never be satisfied, will—and there was a—in the quest to feed it the next (chomp, chomp), the next—the carnivore of it that leads to death because I’m not feeding my spirit, I’m feeding some darkness because my body was breaking down, I was losing my mind in the feeding of this ego. And what’s happening now, and that’s—one-on-one back in the day when I was feeding my ego, as my sole quest, one-on-one what that person thought of me, is how I would choose to behave in a given moment. When I was standing in the DJ booth with 1200 people pulsating to trans music, I was, you know, that animal, what they’re gonna think and feel, what I’m feeding them, what I’m getting back from them, what I’m really consuming that moment, ok, is only deadened and beautifully deadened by what you said – when you put your head on your pillow. Today, it’s what did I do that was an esteem-able act? And that might be something as simple as using my turn signal consistently, pushing the cart back, choosing to in a number of different areas of my life not be the guy in the room, not the only guy in the room, not have an attitude with a checkout person.

Paul: Allow people to be human and make mistakes.

Jamie: The choice of what you’re going to feed, that’s where I think meaning and purpose and a real sense of, I really hesitate to use this word because it’s such a danger zone for me, but a real sense of control. There’s—in the proper, oftentimes most difficult choice, there’s—I’m limiting the options of uncomfortability because, you know, if I choose to do the right thing, just because it’s the right thing to do, and not because of any perceived payoff, what happens is at the end of the day, when it’s time to put my head down on the pillow, oftentimes it will hit me, you know, in afternoon, wow, it’s been a good day, you know. It’s not that anything was done, it’s not that anybody witnessed me do anything wonderful, it’s not that—it’s just kind of like I’m ok with what happened today, you know. I’m OK with raising the bar in certain areas.

Paul: And there seems to be a tradeoff too, you know, the things that the ego likes are usually things that are exciting and instantaneous. And the thing that soul likes I think oftentimes take patience, involve subtlety, and I think involve faith and trust sometimes and that’s 180 degrees from guys like you and me that are wired for I want it yesterday, where the fuck is it? Where’s mine? Don’t you know who I am? Don’t you know who I think I am? But the fact that you are not only alive but you’re flourishing that to me is proof that there’s gotta be a God or something. I mean, the shit that you’ve been through, Jamie.

Jamie: Yeah.

Paul: You’re a fucking miracle, that you are still alive.

Jamie: I’m sure that they said when insulin came into the medical practice that it was the miracle drug, that penicillin at one point was the miracle drug, that to some cancer patients chemotherapy is the miracle drug, so that’s where I disconnect from me being a miracle. I feel that I have experienced that deliverance, I feel chosen, I feel picked, I feel amongst many and I’m more than satisfied with that. From rabbit’s tent to Pauly’s living room. I’ll take Pauly’s living room.

Paul: Well let’s trade a couple of fears. We’re gonna Miles Davis this one and improvise it. I’ll start. I am afraid that by talking about God in this podcast, people will find it boring and will have turned off.

Jamie: I’m afraid that all my big score career-wise opportunities have passed me by.

Paul: Oh boy do I have that one. I’m afraid that I’m never going to be able to fully stand up for advocating for myself and my needs. I’m always going to be a little bit uncomfortable asking for things that really aren’t above and beyond.

Jamie: I’m afraid that I ask too much often and expect far too much and that I make a partnership, whether in business or romantic nearly impossible.

Paul: I’m afraid I’m going to be hobbled much sooner than I think I am, that I’m actually months or several years away from not being able to play hockey anymore.

Jamie: You went there. You bastard.

Paul: Why?

Jamie: I too, you know, because you walked through it with me, my hip replacement almost two years ago, for the past year, the last ten months, I’m better than ever. I can do everything with my right leg. Better range of motion, similar strength, and the past three or four weeks, my left hip has been talking to me and I fear being debilitated.

Paul: I’m afraid that this recent feeling of having my vigor back for life and woodworking and all the things that had kind of gone away with the low grade depression of the last couple of years, I’m afraid that this feeling is only fleeting and temporary and I’m going to be going right back to feeling flat and uninspired again.

Jamie: I’m afraid that I’m gonna miss time with my sons if I continue to smoke.

Paul: I’m afraid that the weight gain these new meds have caused me have made me either unattractive to my wife or even more unattractive to my wife and we’ll wind up getting divorced.

Jamie: I find you very attractive. And, you know, I can’t count how many times in our friendship where you’ve said something that is a new level of honesty and openness and vulnerability, transparency and you’ve set the bar for me so many times. So I’m reaching for the next level of …

I fear that—my girl is fifteen years younger than me—we both keep ourselves in good shape, but I’m 50 and she’s 35, so I fear that when she’s 42 and still smokin’ hot, and I’m getting close to 60 and breaking down, I fear figuring out that she’s too kind to let me know that she’s not attracted to me anymore.

Paul: Let’s go to some loves.

Jamie: Thank you. Do you have a barf bag?

Paul: I love that I’ve just spent an hour-and-a-half sitting here rubbing souls, and the view that I have is of my backyard, which is where I used to fantasize that I would put a gun in my mouth and kill myself.

Jamie: I love that my vulnerability garners me strength every time.

Paul: I love that if I were to be hospitalized with some type of terminal illness, I love knowing that I would be surrounded by people who love me, people from, kind of like my wife and friends, but people from our fellowship, from support groups, many people who we don’t even know each other’s last names, but we know intimate details of each other’s lives and stories and pains and joys and loves and sorrows, and I love that I know that I would be basked in love and support and that that would comfort me no matter how excruciating something I would go through, and that takes—I love that that takes that fear away, that fear of mortality away from me, that fear of what we all fear, at least temporarily it does. I suppose it comes and goes, but—because I’ve seen it in action. You and I have both seen, you know, we lost a friend a couple of months ago to stage four cancer and the hospital he was at, it set a record for the number of visitors. That’s how powerful a support group is, people come out of the woodwork. His family was—had meals brought to them, they were picked up and driven to the airport. And you were one of the people that was there more than anybody else. I love that. I fucking love that.

Jamie: You were talking about your newfound, or re-experiencing your enthusiasm for some of things that you do creatively like woodworking. I have an interest in sculpting and painting that I haven’t gone near in fifteen years and there’s a piece that I’ve been inspired to do based on a letter that I received two weeks ago from Bradley’s mother in gratitude for being there for her son. I love being able to hear that, I love being able to be connected emotionally to the place that that touches and have now—be able to use that like fuel, you know, I love that gratitude is fuel for so many beautiful things.

Paul: I love the feeling of making the unknown my friend and not my enemy. The future and being excited about it and say, “God I can’t wait to see what’s next.” Instead of, “Oh, it’s all gonna be doom, it’s all going downhill.”

Jamie: I love my simple life.

Paul: I think that’s a perfect one to end on.

Jamie, I love you buddy.

Jamie: I love you Paul. Thanks, man, this was fun.

Paul: Many thanks to Jamie for a great episode and just being such a great, loving guy and such an important person in my life.

Before I take it out with a whole bunch of surveys, I want to remind that there’s a couple of different ways to support the show. You can support it financially by going to the website and making a one time PayPal donation, or as I’ve mentioned before, a recurring monthly donation, which makes me very happy. You can also support the show financially, especially now around the holidays, by—if you’re going to buy anything on Amazon, do it through the Amazon search box portal on our homepage. It’s on the right hand side about halfway down. And Amazon gives us a couple nickels, doesn’t cost you anything.

I think I told you last week that we now have some stuff in the Zazzle store, Mental Illness Happy Hour mugs, stuff like that. God I hate talking about this. This is the part, the business part, of doing the podcast that I just hate. It would be nice if money just came down the chimney. Then I could just not have to deal with any of this other stuff. Oh my childlike opinion of how the world should work.

Oh you can support the show non-financially by going to iTunes and giving us a good rating, and that boosts our ranking and brings more people to the show. And you can also help us by spreading the word through social media. That makes me very happy when I see people doing that.

I think that’s about it for the announcements. I’m sure I’ll think of something. And all the people that make this show possible, of course, I want to thank you. You know who you are.

This first survey, I’ve got a huge stack, I’m not going to get through all of them, but I’m just gonna read them until either I feel your interest waning or you just becoming sick of my voice. Maybe both will happen at the same time. Kismet! This is from the Shame and Secrets survey, filled out by Amelia, a woman who’s straight, she’s in her twenties, raised in a stable and safe environment, was the victim of sexual abuse but never reported it, “Deepest darkest thoughts?” “I think about all the ways I can use technology to ruin the lives of the people who have hurt me. I want them to suffer. I want their relationships to be ruined. I want to be shamed by their coworkers. I want them to learn what it’s like to wish you were dead and feel like your entire existence was one big fucking mistake.”

“Sexual fantasies most powerful to you?” “I can’t really answer a question about a sexual fantasy when I hate sex and I hate being touched. Even being touched by someone who has no sexual thoughts towards me is enough to make my entire body tense up.”

“Would you ever consider telling a partner or close friend your fantasies?” She writes, “Ha. You think I can get a partner like this? Would you want to be around someone who took every touch as a threat?”

“Do these thoughts or secrets generate any particular feelings towards yourself?” She writes, “The gun in my closet is sometimes the only hope I have.” I’m sorry, the printer kind of fucked up and I couldn’t read the line, that was the answer to the question of, “Deepest darkest secrets?”

“Do these thoughts or secrets generate any particular feelings towards yourself?” She writes, “I feel like I have a monster living inside that I created. I fed this monster for 20 years and it feeds on self-loathing. It gets its kicks from watching me abuse myself and it loves the days I walk to cliff and look over. The monster speaks to me when no one else does because it knows my soul is dead. I fear I’m becoming worse than the monster ever anticipated and it’s all part of a cruel joke.”

I don’t know what to say. Just sending some love your way, Amelia. I know it’s hard to believe that you’re not alone but there are other people that feel that way, and there are people who have felt that way and then managed to not feel that way without taking their lives. I’m sending a big, big, fat hug your way.

This next one is filled out by a guy calls himself Buzz, he’s straight, he’s in his ‘20’s, was raised in an environment that was pretty dysfunctional, never been sexually abused. “Deepest darkest thoughts?” “I’m a recovering addict and I used to fantasize about suicide a lot. It’s been years since I’ve wanted to die, but I definitely still sometimes feel like the idea of there being no afterlife is the only that really scares me about death. I’ve also had a lot of sexual thoughts about the serious girlfriends/fiancés of my good friends. I’ve never allowed myself to “use” their images after the became my friends’ wives.” Boy, that is a, I don’t know what the word would be but that’s a guy with some serious ethical boundaries not allowing yourself to even think about them once they’re married. That, man, if I had a nickel for every inappropriate person I masturbated thinking about, we would have a new lotto.

“Sexual fantasies most powerful to you?” “I fantasize about women, especially colleagues, making the first move. I’m sexually passive, deeply intimidated by attractive women and always afraid of making them uncomfortable. For some reason I’ve always wanted to perform anal sex on a woman.” Buzz, there doesn’t have to be a reason.

“Deepest darkest secrets?” “When I was still in puberty—I hope this doesn’t seem like I’m being defensive or rationalizing—I had fantasies about close relatives.”

“Do these secrets and thoughts generate any feelings towards yourself?” He writes, “Self-hatred. The hope that those kind of feelings are genuinely gone and not buried in my subconscious waiting to cause problems later in life.” You sound like a good guy, Buzz, who is very conscientious towards other people, perhaps, perhaps, I don’t know if you can be too conscientious towards other people but very respectful of other people’s boundaries and I think definitely too hard on yourself. Way too hard on yourself. You sound like a good guy.

This is filled out by a guy who calls himself Alter Boy, straight, in his 40’s, was raised in an environment totally chaotic, was the victim of sexual abuse, never reported it. “Deepest, darkest thoughts?” “That it would be a blessed release for me to die. That my wife and daughter would be better off without me. That although I had a lot to offer the world at one point, I am now trapped in a career I hate, living in an area I can’t stand, I am unable to pursue anything that I find fulfilling.” I can’t tell you how many people feel that same way. I can’t tell you how many people feel that same way – a lot.

“Sexual fantasies most powerful to you?” “Being dominated by a strong woman, having her lift her skirt up and shove my face into her crotch, which is hot and sweating from the pantyhose she still wears. Having her make me fuck her while a tranny with a big thick cock fucks me and explodes in my ass.” By the way, transgendered people don’t like being called trannies. It’s kind of, it’s kind of become a derogatory, very weighted word, and I know you certainly didn’t mean it in a derogatory way, so I’m not trying to shame you. Yeah, that sounds like a good fucking healthy fantasy to me. And the nice thing about having a woman jam her face into her crotch, no matter how hard she does it, that’s a soft landing. There’s nothing really created on the planet to cushion better and with more love than a vagina. If only all head-on collisions could be into a welcoming vagina. I’m gonna phone the DMV and see what they think about that one. How many words in that sentence get out before the call is traced and the FBI pulls me out of my house with my shirt off? I don’t think the FBI ever pulls you out, even if your shirt isn’t off, you gotta take your shoes off when you see them coming, just to keep up that stereotype.

“Would you ever consider telling a partner or close friend your fantasies?” He writes, “No, I can’t even get her to let me eat her out.” That is a bummer. Who doesn’t like to have oral sex performed on them? You know, a thought just occurred to me, is somebody probably did that to her against her will when she was younger. And maybe that would be something to, I don’t know, get her to talk about, but I don’t know how you broach that subject without—I don’t know what you would say, maybe, I don’t know, a therapist would probably find a good way for you to bring that subject up, but that to me just screams sexual abuse in her past. Or she doesn’t wipe her ass. Ding dong! I fucking love having my own podcast, I fucking love it. I love that I can say whatever I want. Hello helicopter. It’s coming in with the FBI to pull me out without my shirt on.

“Deepest, darkest secrets?” “I’m in capable of looking at a woman without searching for one thing about her physically that turns me on and then proceed to create a sexual fantasy about that thing. It happens all the time everywhere.” I think that’s pretty normal. You know, I’ve shared before that I can be standing behind a woman in line for coffee and just by looking at the back of her neck begin fantasizing about things, just based on the way the back of her neck looks like, I think that’s just being a human being.

“Do these secrets and thoughts generate any particular towards yourself?” He writes, “It makes me feel like a worthless piece of shit, a scumbag and a vile human being.” I don’t think you’re being hard enough on yourself. Obviously I’m being sarcastic. I want to give you a big hug. Against your will. A big inappropriate, loving hug that you don’t want.

This next survey wall filled out by—I hope you’re still with me, I’d like to think that this is—I still have your interest, however many minutes in—this is filled out by a woman who calls herself Angry Elephant. I don’t like where this is going. Any woman that calls herself Angry Elephant—ah, the dogs are gonna bark, my wife just came home. She’s straight, she’s been celibate for the 20 years or so, in her 40’s. (dogs bark) There we go, I’m gonna pause.

All right, they’ve calmed down. Angry Elephant, um, “Ever been the victim of sexual abuse?” “Some stuff happened, but I don’t know if it counts as sexual abuse. I feel like I was sexualized by my dad and turned into his companion at one point in my teens, more emotional abuse. I had to listen to his rants and raves and anger.” Boy, do I fucking relate to you.

“Deepest, darkest thoughts?” And that wasn’t my dad, it was my mom. “Deepest darkest thoughts?” “Punching my neighbor in the face when he blatantly looks at the warped side of my nose from a botched nose job.”

“Sexual fantasies most powerful to you?” “I feel too fat and out of shape to have sex.” You are NEVER too fat or out of shape to have sex. Let—I want that on my tombstone. I want that on my tombstone. And if I could get somebody to chisel in stone like a picture it would be a big, fat, out-of-shape ass just fucking getting it on. Everybody deserves to have sex if they want it. “When I’m feeling, when I’m feeling sexual, which is rare, totally based on hormones, and chemicals, I watch free online porn. My fantasies are pretty boring.” Does anybody watch pay porn anymore? There’s so much free porn out there it—I suppose if you’re into something really specific that’s hard to find you would have to pay for it, but ….

“Would you ever consider telling a partner or close friend your fantasies?” The printer kind of fucked this up. “Having sex and being intimate with someone who I can trust and care about seems like…” Goddamn you printer—I can’t—it printed like only half of the text so I can’t really see it.

“Deepest darkest secrets?” “My dad always made inappropriate comments. I lived at home for many years because of depression and anxiety. I freaked out when it felt like he made a moaning sound when I was driving with him in a car. It was in response to something I said that seemed like a sexual come on towards me. It scared me and I moved out to finally get away from him and his emotional abuse. In order to see my mom I have buried it and all the other creepy things.” By the way, that to me, if it was that one thing, I would say, “Um, maybe you misinterpreted it.” But one of the things that I’ve learned to do in dealing with people I’ve had lifelong relationships with is to look at the pattern, the pattern doesn’t lie. “I pretend they didn’t happen. When he is not a weirdo, he is a smart, good man, but when I go back to that place, I hate him and I cannot believe I still have to have a relationship with him. I hope he dies before my mom because I refuse to take care of him.”

“Do these secrets and thoughts generate any particular feelings towards yourself?” She writes, “It makes me feel like I create these situations. That it is my fault because I lived at home so long. I felt helpless.” And by the way, I don’t know if you know how wrong that sounds. It doesn’t matter if you live with your parents for the rest of your lives, that doesn’t give the right to sexualize you. “I felt helpless and then started to wish he would die. It is creepy, subtle. My mom is passive and I resent her for it. Whenever I talk about how people treat me to my mom, people feel like my feelings are invalidated and I am made to feel like either I am making it up or I am just being paranoid.” If I could just interject – get to a support group because you will find a room of people who know exactly how you feel and you will feel validated. She writes, “I feel like my feelings are invalidated—“ Oh I read that, “And I’m made to feel like either I am making it up or I am just being paranoid. I feel like because of my anxiety problems I will never be in love or have a healthy relationship. I feel like I will be alone for the rest of my life. I feel like if I’m intimate with someone and I enjoy sex, that I am a slut and a bad person. Ever since I quit drinking years and years ago, I’ve avoided dating and sex. If I meet someone I’m sexually attracted to, I get completely wigged out and I run away because I cannot handle my feelings. I feel like I will never have a passionate, loving relationship because I am so shy. I think it is also why I stay fat, because then men are not as attracted to me.” This—again, I am not a therapist, I am not a mental health professional, but this is such classic fear of intimacy because somebody abused your trust, obviously your dad. And there is help. This is so common and this is so treatable but it involves you opening up and talking to people and seeing somebody who can help you – a therapist, a support group, etc., etc. I’m sorry if I sound like a broken record but when I see somebody whose situation is so similar to mine, and I’ve been able to process it and be at peace with it and learn how to be intimate, and being intimate is fucking awesome. It is fucking awesome, being intimate and vulnerable is just… All right, I’m running my mouth now. She also adds, “I would like to hear someone who has struggled with social phobia like me.” I’ve actually had many people be guests on this show who talk about social phobia – Steve Agee talks about it, Eddie Pepitone, a bunch of others, some of whom I’m blanking on right now. “My head twitches when sexual words come up if I’m in a group. I have to take a Klonopin so I can function in group situations because I have a phobia of words. I was in a lecture once and the teacher said ‘hard’ and my head twitched involuntarily, followed by intense humiliation. I felt so embarrassed. I think out of everything it is the worst. I become afraid that they are going to say ‘hard’, ‘hotel room,’ ‘bed,’ ‘body,’ anything that could be sexual. I get so uptight. I was in this lecture about computers and she kept saying ‘hard drive.’ I became afraid of her saying ‘hard drive.’ I held my head the entire class so it wouldn’t twitch. This is so ridiculous that I have only told my therapist. Sorry this is so long.” Well that’s good that you’ve told your therapist. I think a support group would be awesome for you. And you’re not a bad person, you’re not a flawed person, anymore than anybody else. I just think you have been emotionally abused. And don’t ever underestimate the effect that that can have on a child. When the person that is supposed to be in their care is abusing that trust and the privilege of raising that child.

You know, I think that’s enough, that’s enough for now. I don’t want to end this one on a down note. I wish I had a big, like, an audio version of a seltzer bottle I could squeeze at the end to brighten things up but hopefully, having listened to Jamie’s interview, there’s a—those of you that aren’t feeling much hope are feeling a little bit more hope. Just months ago, I was seriously considering being hospitalized because the feelings of sadness I was experiencing were so overwhelming, I didn’t think I was going to be able to hang on without being hospitalized. And I’ve never been in a better place than I am right now because I processed it. I talked to people about it. And I did the work that was suggested to me by mental health professionals. I can’t say enough good stuff about EMDR. My new therapist is doing it and I think that is part of what is really helping me rewire my brain and that’s a miracle. Thank you guys for listening. And those of you that are still feeling stuck, I love you. I may not know you, but I think I know what you feel. And that’s one of the things that bonds us all together. We are not in this alone. You are not alone. Thanks for listening.

[SHOW OUTRO]

Sue McPherson

08/13/2019 at 2:29 pmIs the podcast available for this episode?